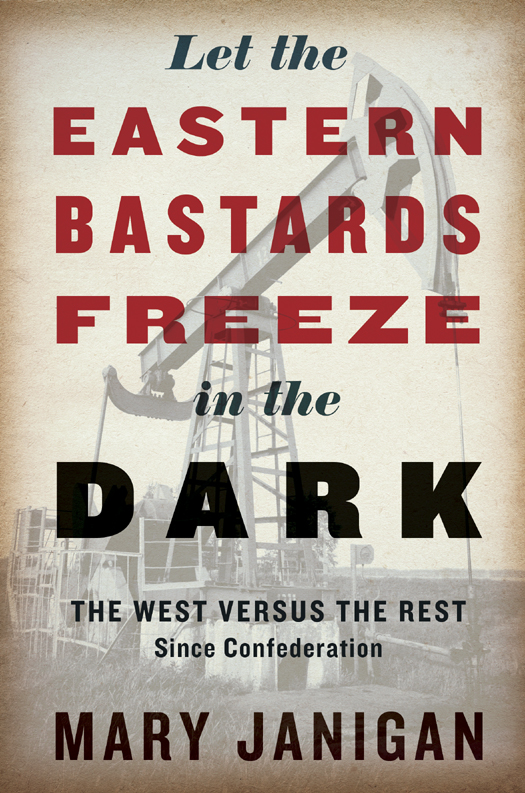

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2012 Mary Janigan

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2012 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

www.randomhouse.ca

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Janigan, Mary

Let the eastern bastards freeze in the dark / Mary Janigan.

eISBN: 978-0-307-40064-2

1. RegionalismCanada, Western. 2. Federal-provincial relationsCanada, WesternHistory. 3. Canada, WesternPolitics and government. 4. Natural resourcesCanada, Western. I. Title.

FC 3209. A 4 J 36 2012 971.202 C 2012-902094- X

Cover design by Leah Springate

v3.1

For Tom Kierans. Always.

CONTENTS

1 THE NOVEMBER 1918 CONFERENCE:

WHERE THE WEST WAS ALMOST LOST.

2 RIEL VERSUS MACDONALD:

CONTENDERS FOR THE WEST. 1857 TO SUMMER OF 1870

3 NORQUAY AND HAULTAIN:

TWO WESTERN CHAMPIONS AND A FUNERAL. LATE 1870 TO 1897

4 HAULTAIN LOSES SELF-CONTROLAND LAURIER KEEPS

RESOURCE CONTROL. 1898 TO 1905

5 A BURDEN ONEROUS TO BEAR:

FRANK OLIVER DOES IT HIS WAY. 1905 TO AUGUST 1911

6 BORDEN DALLIES:

THE BIRTH OF THE GANG OF THREE. SEPTEMBER 1911 TO AUGUST 1914

7 THE WESTS BAD WAR:

STALEMATE FOR THE GANG OF THREE. AUGUST 1914 TO EARLY MARCH 1918

8 THE REST VERSUS THE WEST:

THE GANG OF Three LOSES THE PEACE. MARCH 1918 TO NOVEMBER 1918

Preface

I T WAS A SULTRY DAY IN LATE J UNE when Stphane Dion marched into the boardroom of the Globe and Mail to explain his proposal for a federal carbon tax. The Liberal leader was idealistic and fervent. He was also impatient and implacable. His taxwhich would particularly affect oil and natural gas producerswould raise more money in the West than it would in other regions. Much of the cash would be earmarked for the fight against national child poverty. When asked how Westerners would react to this federal cash grab, the former political science professor was dismissive: it would be good for them. Good for them? They would be forced to diversify their economy, came the response.

Stephen Harper would make mincemeat of Dion. The prime minister would compare his opponents scheme to the National Energy Program of the early 1980s, dismiss it as insane, and warn that it would screw everybody.

What kind of language was this? How had a theoretical discussion about the best way to curb greenhouse gas emissions degenerated into this squabble between the Montreal-based Opposition leader and the Calgary-based prime minister? How could these politicians recklessly push regional buttons? Why was a provincial carbon tax permissibleAlberta had imposed a small tax on excessive emissionswhile a federal tax was an intrusion, even for the many Albertans who deplored the Oil Sands emissions? It was almost as if Harper and Dion were speaking in code, eliciting responses that were bred in the bone. Less than four months later, Dion would lose the 2008 federal election, emerging with one seat in Manitoba, one seat in Saskatchewan and no seats in Alberta. The issue of resource control had conjured up another regional divide.

This book was born on the day that Dion preached to the unconverted. It is the tale of how the West was colonized, as immigrants streamed onto Prairie land that Ottawa was virtually giving away. It is also the tale of how the West was almost lost when Ottawa would not release its iron grip on the Wests lands and resources, largely because the Rest of Canada ferociously objected to any transfer.

Most important, this is the forgotten story of Canada. Fights over resource control are woven into the very fabric of the nation. Maritimers do not remember that their premiers once claimed they had bought the West, fair and square, so they owned the Wests lands and resources. Residents of Quebec and Ontario have no idea that their premiers once demanded much higher subsidies if the Prairie provinces secured control over their lands and resources. British Columbian residents do not know that their premiers once hotly insisted that their twentieth-century claims to huge chunks of federally controlled land trumped the Wests long-standing demands.

The federation was dysfunctional. The Wests battle for control over its lands, minerals, oil and natural gas, forests, and waterpower brought out the worst in every region. There are no heroes in this narrativealthough the wily politician who brokered temporary peace pulled off a remarkable coup. The cast of characters includes larger-than-life leaders who towered over their times, whose every utterance was once chronicled but who are only remembered now in obscure place names. There was high drama and great anger; there was greed and jealousy. There was political clumsiness. The stress likely contributed to the death of one premier. Another waged an epic door-slamming argument with a prime minister. The provinces fought with each other and with Ottawa, as alliances formed and shifted. Politicians said and did both foolish and damaging things.

The battle lines over resource control were drawn early on the Canadian frontier. Disputes first flared in the mid-nineteenth century when Ottawa paid 300,000 British pounds to the Hudsons Bay Company, and acquired the vast terrain of Ruperts Land and the North-Western Territory. When the Mtis resisted that transaction, the federal government carved a truncated Manitoba out of its new turf, and set about the business of settling immigrants on its acquisitions. Ottawa wanted a colony, docile and rich; it kept legal control of the resource wealth in Manitoba and the renamed Northwest Territories. The West disputed Ottawas schemes: virtually from the beginning, Manitoba and Territorial legislators sought more power and more money. Also from the beginning, Ottawa resisted, making only minor concessions to keep the peace. And from the beginning, the Rest of Canada opposed any federal transfer, turning the West into a pawn in their disputes with each other and Ottawa.

It was an unfortunate quarrel that spanned generations. Westerners were embittered because the other provinces controlled their resources. The four original partnersQuebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia and New Brunswickretained full control over their own resources when they agreed to confederate in 1867. British Columbia kept resource control when it joined in 1871; so did Prince Edward Island in 1873. The constitutional inequality rankled.

The quarrels reached a nadir at a now-obscure federalprovincial conference in November of 1918. Only eight days after the end of the Great War, the nine premiers trooped to Ottawa to discuss the daunting challenges of the peace. On Ottawas official agenda were three issues: the problem of settling the returning soldiers on the land; the difficulty of luring more settlers onto the land; and the Prairie provinces request for the transfer of their resources. The conference spanned four days, and the ensuing minutes are brief.