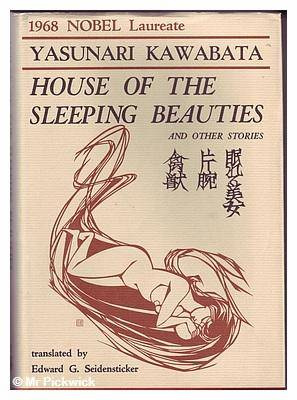

Yasunari Kawabata

The House of the Sleeping Beauties

He was not to do anything in bad taste, the woman of the inn warned old Eguchi. He was not to put his finger into the mouth of the sleeping girl, or try anything else of that sort.

There was this room, of about four yards square, and the one next to it, but apparently no other rooms upstairs. And, since the downstairs seemed too restrict for guests rooms, the place could scarcely be called an inn at all. Probably because its secret allowed none, there was no sign at the gate. All was silence. Admitted through the locked gate, old Eguchi had seen only the woman to whom he was now talking. It was his first visit. He did not know whether she was the proprietress or a maid. It seemed best not asked.

A small woman perhaps in her mid-forties, she had a youthful voice, and it was as if she had especially cultivated a calm, steady manner. The thin lips scarcely parted as she spoke. She did not often look at Eguchi. There was something in the dark eyes that lowered his defenses, and she seemed quite at ease

She made tea from the iron kettle on the bronze brazier. The tea leaves and the quality of the brewing were astonishingly good for the place and the occasion to put old Eguchi more tranquilized. In the alcove hung a picture of Kawai Gyokud, probably a reproduction, of a mountain village warm with autumn leaves. Nothing suggested it room had unusual secrets.

"And please do not try to wake her. Not that you could, whatever you did. She is soundly asleep and knows nothing."

The woman said it again: "She will sleep on and on and knows nothing at all, from start to finish. Not even who's been with her, You needn't worry."

Eguchi said nothing of the doubts that were coming over him.

"She is a very pretty girl. I only take guests I know I can trust."

As Eguchi looked away his eye fell to his wrist watch.

"What time is it?"

"A quarter to eleven."

"I should think so. Old gentlemen like to go to bed early and get up early. So whenever you're ready."

The woman got up and unlocked the door to the next room. She used her left hand. There was nothing remarkable about the act, but Eguchi held his breath as he watched her. She looked into the other room. She was no doubt used to looking through doorways, and there was nothing unusual about the back turned toward Eguchi.

Yet it seemed strange. There was a large, strange bird on the knot of her obi. He did not know what species it might be. Why should such realistic eyes and feet have been put on a stylized bird? It was not that the bird was disquieting in itself, only that the design was bad. But if disquiet was to be tied to the woman's back, it was there in the bird. The ground was a pale yellow, almost white.

The next room seemed to be dimly lighted. The woman closed the door without locking it, and put the key on the table before Eguchi. There was nothing in her manner to suggest that she had inspected a secret room, nor was there in the tone of her voice.

Here is the key. I hope you sleep well. If you have trouble getting to sleep, you will find some sleeping medicine by the pillow.

"Have you anything to drink?"

"I don't keep spirits."

"I can't even have a drink to put myself to sleep?"

"No."

"She's in the next room?"

"She's asleep, waiting for you."

"Oh!" Eguchi was a little surprised. When had the girl come into the next room? How long had she been asleep? Had the woman opened the door to make sure that she was asleep? Eguchi have heard by an old acquaintance who frequented the place that a girl would be waiting, asleep, and that she would not awake. But now that he was here he seemed unable to believe it.

"Where will you undress?" She seemed ready to help him. He was silent. "Listen to the waves. And the wind."

"Waves?"

"Good night." She left him.

Alone, old Eguchi looked around the room, bare and without contrivance. His eye came to rest on the door to the next room. It was of cedar, some three feet wide. It seemed to be put in after the house was finished. The wall too, upon examined well, seemed once to have been a sliding partition, now sealed to form the secret chamber of the sleeping beauties. The colour was just that of the other wall, but it seemed fresher.

Eguchi took up the key. Having done so, he should have entered into the other room. But he remained seated. I was as the woman had said: the sound of the waves was violent. It was as if they were beating against a high cliff, and as if this little house were at its very edge. The wind carried the sound of approaching winter, perhaps because of the house itself, perhaps because of something in old Eguchi. Yet it was quite warm enough with only the single brazier. The district was a warm one. The wind did not seem to be driving leaves behind it. Having arrived late, Eguchi had not seen what sort of country the house lay in. But there had been the smell of the sea. The garden was large for the size of the house, with considerable number of pines and maples. The needles of the pines lay strong against the sky. The house had probably been a country villa.

The key still in his hand, Eguchi lighted a cigarette. He took a puff or two and put it out. But a second one he smoked to the end. It was less that he was ridiculing himself for the faint apprehension than he was aware of an unpleasant emptiness. He usually had a little whiskey before going to bed. He was a light sleeper, given to bad dreams. A poetess who had died young of cancer had said in one of her poems that for her, on sleepless nights, 'the night offers toads and black dogs and corpses of the drowned'. It was a line that Eguchi could not forget. Remembering it now, he wondered whether the girl asleep no, put to sleep in the next room might be like a corpse from a drowning. And he felt some hesitation about going to her. He had not heard how the girl had been put to sleep. She would in any case be in an unnatural stupor, not conscious of events around her, and so she might have the muddy, leaden skin of racked by drugs. There might be dark circles under her eyes, her ribs might show through a dry, shriveled skin. Or she might be cold, bloated, puffy. She might be snoring slightly, her lips parted to show purplish gums. In his sixty-seven years old Eguchi had passed ugly nights with women. Indeed, the ugly nights were the hardest ones to forget. The ugliness had had to do not with the appearance of the women, but with their tragedies, their warped lives. He did not want to add another such episode, at his age, to the record. So ran his thoughts, on the edge of the adventure. But could there be anything uglier than an old man lying the night through beside a girl put to sleep, unwaking? Had he not come to this house seeking the ultimate in the ugliness of old age?

The woman had spoken of guests she could trust. It seemed that everyone who came here could be trust. The man who had told Eguchi of the house was so old that he was no longer a man. He seemed to think that Eguchi had reached the same stage of senility. Probably because the woman of the house, probably because she was accustomed only to make arrangements fir such old men, she had turned upon Eguchi a look neither of pity nor of inquiry. Still able to enjoy himself, he was not yet a guest to be trusted. But it was possible to make himself one, because of his feelings at that time, because of the place, because of his companion. The ugliness of old age pressed down upon him. For him too, he thought, the dreary circumstances of the other guests were not far off. The fact that he was here surely indicated as much. And for he had no intention of breaking the ugly restrictions, the sad restrictions imposed upon the old men. He did not intend to break them, and he would not. Though it might be called a secret club, the number of old men who were members seemed to be few. Eguchi had come neither to expose its sins nor to pry into its secret practices. His curiosity was less than strong, because the dreariness of old age lay already upon him too.

Next page