The Life and Death

of YUKIO MISHIMA

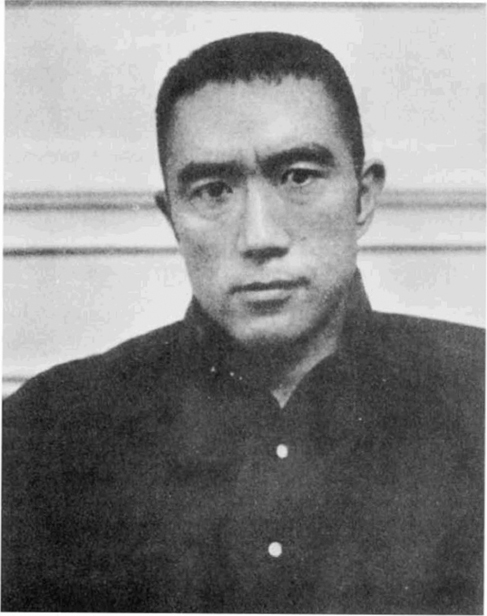

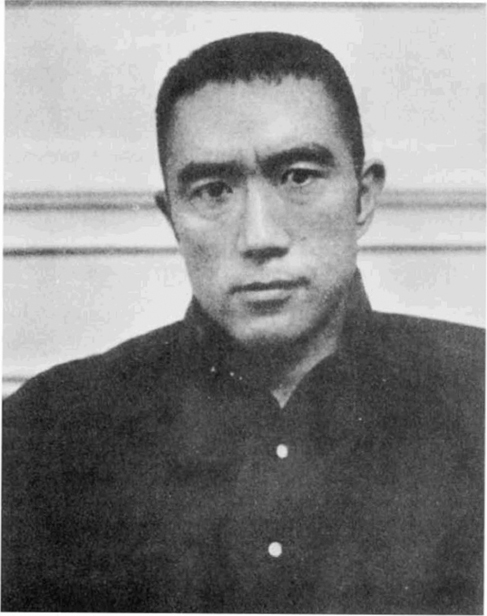

Photo: UPI

The Life and Death

of YUKIO MISHIMA

Henry Scott Stokes

First Cooper Square Press edition 2000

This Cooper Square Press paperback edition of The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima is an unabridged republication of the edition published in New York in 1995. It is reprinted by arrangement with Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc.

Copyright 1974, 1995, and 1999 by Henry Scott Stokes

Designed by Paula Wiener

Grateful acknowledgment is extended to Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., for permission to quote from their copyrighted translations of the works of Yukio Mishima.

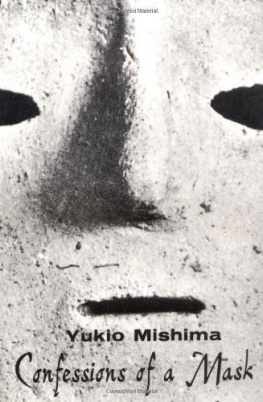

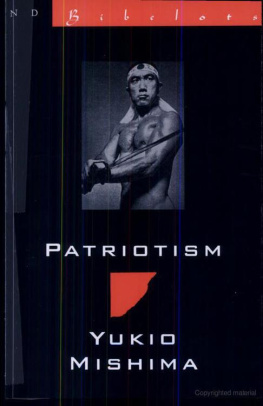

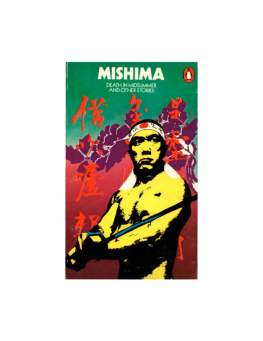

We are also grateful to New Directions Publishing Corporation for permission to quote from two works by Yukio Mishima, Death in Midsummer and Other Stories, copyright 1966 by New Directions Publishing Corporation; reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation. Yukio Mishima, Confessions of a Mask, translated by Meredith Weatherby, copyright 1958 by New Directions Publishing Corporation; reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation.

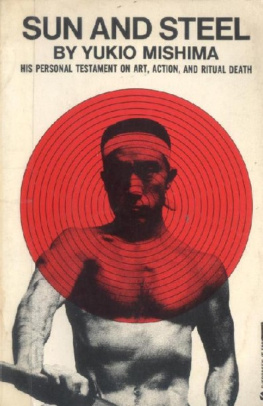

Grateful acknowledgment is also extended to Kodansha International Ltd for permission to quote from their copyrighted translation by John Bester of Yukio Mishimas Sun and Steel, and from Landscapes and Portraits by Donald Keene.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Published by Cooper Square Press

An Imprint of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group

150 Fifth Avenue, Suite 911

New York, New York 10011

Distributed by National Book Network

ISBN 0-8154-1074-3

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992. Manufactured in the United States of America.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992. Manufactured in the United States of America.

For Gilbert de Botton

CONTENTS

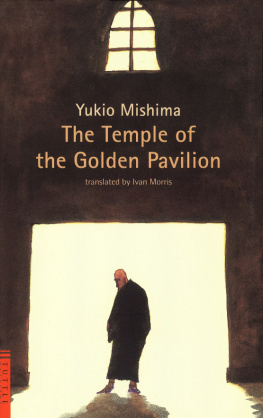

Beauty, beautiful things, those are now my most deadly enemies.

Yukio Mishima, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

The Life and Death

of YUKIO MISHIMA

PROLOGUE

A Personal Impression

I first encountered Yukio Mishima, whose name is pronounced Mi-shi-ma with short vowels, on April 18, 1966, when he was to make an after-dinner speech at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan in Tokyo, as our guest of honor. At that time, then only forty-one, Mishima was already confidently spoken of as a future winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. He came with his wife, Yko. The Mishimas took their seats at a head table, flanking John Roderick, an Associated Press journalist who was then president of the club. I was seated at a little distance from the top table, but I observed that Mishima was small, wiry in physique, and briskhe had his hair cut very short, almost in a crew cut. His skin had a slightly unhealthy pallor. No doubt he was working himself too hard, I thought, knowing that he always wrote straight through the night. Mishima spoke fluent English. Yko was a complete contrast. Also small, she was ten years younger than her husband and looked it. Petite, with a round face, she kept her counsel and spoke littleshe had, by that time, two very young children.

In his introductory remarks that night Roderick described the career and achievements of Yukio Mishima. He was born Kimitak HiraokaYukio Mishima was a pen namein 1925, the eldest child of an upper-middle-class family living in Tokyo. His school record had been excellent and he had graduated top of his class at the exclusive Gakushin (the Peers School) in 1944. At the age of nineteen he had traveled to the palace in central Tokyo to receive a prize, a silver watch, from Emperor Hirohito in person. (The following year, 1945, he had received a summons to an army medical, as a draftee, but he had failed that medical and had never served in the Japanese Imperial Army.) After the war, following graduation from the elite Tokyo University Law Department, he had taken the toughest job examination of all, the Ministry of Finances entrance examination, and passed with flying colors. Yet he had rejected a career in governmenthe would surely have pressed on to become a bank president or the likeand had opted to become a writer, a still more competitive choice of career. Seizing his opportunity, he completed a first major work, Confessions of a Mask, published in 1949, a book that touched on homosexual themesand made him famous. At twenty-four he was hailed as a genius by Japanese critics. Thereafter, he published novels one after another at rapid speed. His outstanding works were The Sound of Waves (1954), a retelling of the romantic legend of Daphnis and Chlo in a Japanese setting, and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), a novel based on a celebrated arson incident in Kyotonot long after wars end, a monk set fire to one of Kyotos most famous old temples, burning it to the ground. Both works were translated and published in America in the 1950s (though publication of Confessions of a Mask was delayed for a couple of years after its actual translation, to allow The Sound of Waves, a less controversial work, to come out first and to set Mishimas reputation in the West as an uncommonly brilliant new writer). Mishima, said Roderick, was not only a novelist. He was a playwright, a sportsman, and a film actor. He had just completed a film of his short story Patriotism, a movie in which he played the part of the protagonist, a young army officer of the 1930s who committed suicide with his wifethe officer by hara-kiri, his wife by cutting her throat. Mishima was a man of many parts, concluded Roderick, a Leonardo da Vinci of modern Japan. That reference to Leonardo sounded a shade exaggerated, and it was delivered with a deliberate smile.

Mishima then stood up. He spoke, mainly, of his wartime experiences. He described the bombing of Tokyo in March 1945 and the appalling fires that swept the city, killing hundreds of thousands of Tokyoites on the worst night. It was the most beautiful fireworks display I have ever seen, he said in a jocular manner. Finally, he came to his peroration, concluding in his forceful if grammatically incorrect English, and spiking the ending with a surprising reference to his wife (Yko has no imaginationspoken with a comic grimace):

But sometime, sometime during such a peaceful life [Mishima had spoken of his married life]we got the two childrenstill the old memory comes to my mind.

It is the memory of during the war, and I remember one scene which happened during the war, when I was working at the airplane factory.

One motion picture was shown there for the entertainment of the working students, which was based on the novel of Mr. Yokomitsu. And it was maybe Maytime of 1945, the very last of the war, and all studentsI was twentiescouldnt believe that we could be survived after the war. And I remember one scene of the film. There was a street, a street scene of Ginza, before the war, a lot of neon signs, beautiful neon signs; it was glittering and we believed we couldnt see all in my life, we can never see it all in my life. But, as you know, we

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992. Manufactured in the United States of America.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992. Manufactured in the United States of America.