Persona

A Biography of Yukio Mishima

Naoki Inose

with Hiroaki Sato

Stone Bridge Press Berkeley, California

Published by

Stone Bridge Press

P. O. Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707

510-524-8732

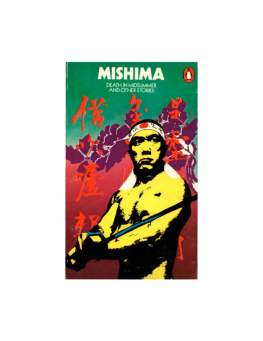

Front jacket design by Noda Masaaki and Noda Emi.

Back jacket photograph Museum of Modern Japanese Literature, Tokyo. Used by permission.

Text 2012 Naoki Inose and Hiroaki Sato.

This is an expanded adaptation in English of Persona: Mishima Yukio den, published in 1995 by Bungei Shunj (Tokyo, Japan).

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Inose, Naoki.

[Perusona. English]

Persona: a biography of Yukio Mishima / Naoki Inose; with Hiroaki Sato.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61172-008-2 (cbk); ISBN 978-1-61172-524-7 (ebk).

1. Mishima, Yukio, 19251970. 2. Authors, Japanese20th century

Biography. I. Sato, Hiroaki, 1942. II. Title.

PL833.I7Z63713 2012

895.6'35dc23

[B]

2012030595

For Ron Bayes and Rand Castile

The range, variety, and publicness of the career sound ominously familiar to me....

I only regret we never met, for friends found him a good companion, a fine drinking partner, and fun to cruise with.

GORE VIDAL

Mishima definitely lived. He was a true genius in living.

NOSAKA AKIYUKI

Preface

This is an expanded adaptation in English of Inose Naokis biography Persona: Mishima Yukio den (Bungei Shunj, 1995). Inoses Persona is a unique depiction of the bureaucratic and political aspects of Japanese history since the late nineteenth century as they relate to Mishima. This English adaptation greatly augments Mishimas literary, theatrical, and ideological theories and activities, not to mention his pursuit of various sports, to suggest how he brought them all together into one focus: death.

Since Inose wrote Persona, partly based on interviews conducted in 1994, a number of things have changednotably, Japans bureaucratic structures and positions in consequence of administrative reforms in the past dozen years. But such things are left as they were up to the mid-1990s so far as they do not affect this account of Mishimas life.

In this book, all Japanese names are given the Japanese way, family name first (except on the cover). Following Japanese custom, Japanese people are sometimes referred to by their personal name, rather than by their surname. Among the prominent writers since the late nineteenth century this occurs most notably with Natsume Sseki, who is usually called Sseki, and Mori gai, gai. Mishima Yukio was the penname of Hiraoka Kimitake. His teachers and school friends most often addressed him by his surname with or without a post-nominal compellation: -sama, -san, -kun. His family members or close friends usually called him by his personal name, often by his pet name, Kimichan or K-chan, the second one because the sinified pronunciation of Kimitake is Ki.

The macron is used to indicate a long vowel in Japanese except where common use makes it needlessly conspicuous (as in Tky for Tokyo) and where the theaters and other establishments have their own roman spellings (as in Nissay for Nissei in the theater name).

The word tenn, usually translated as emperor, is retained in this book, except when used as a title, as in the Emperor Meiji, and in a few other circumstances. This is because the Japanese word, along with the English word emperor, has created a host of misconceptions, both in Japan (intentionally) and abroad (willfully) after the country tried to join the imperialist powers in the second half of the nineteenth century. More important, the tenn institution had a special meaning in Mishimas thinking all his life, but particularly when it came to the fore in his argument on Japanese history and Constitutions.

Unless noted, translations from the Japanese are all mine.

Many people have helped to make this this expanded English adaptation possible, starting with Inose Naoki. He sent me books, including many of his own, answered questions, and provided me with some of the interview transcripts. The unreferenced quotations in this book come from the interviews he conducted.

Hirata Shigeru, Ishii Tatsuhiko, Takagaki Chihiro, and Kakizaki Shko helped to collect books for this biography. Among them, Shkosan is hardest to thank. She went out of her way to find and buy many books for me.

Kyoko Selden helped me with a range of things with her erudition; she also found for me part of a text of Le Martyre de Saint Sbastien at Cornell University Library. Ishii Tatsuhiko acquired a number of articles related to Mishima and helped me with his extensive knowledge of theater. Jeffrey Angles made many magazine articles in English available to me online. Alexander Truskinovsky acquired for me Melvin J. Laskys A Letter from Salzburg, a lively account of the selection process of the fourth Formentor Literary Prize, in 1961. Ken Aoki at The Institute for Medieval Japanese Studies, Columbia University, copied for me Kihira Teikos Mishima Yukio no tegami, an account of her association with Mishima in the early postwar years that was serialized in eighteen installments in the weekly Asahi, from December 13, 1974 to April 11, 1975.

Lili Selden sent me the English translations of Akutagawa Rynosukes story, Butkai, and Pierre Lotis story, Un Bal a Yeddo.

Col. Jaxon Teck and his wife, Arlene, helped me with US military terms; Arlene also edited one chapter. Ueda Akira and Takii Mitsuo got in touch with the Japan Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to clarify certain matters. Akira-san also gave me information on Tokyo that I, a New York City resident, could not readily acquire, such as distances and the state of certain institutions. Noguchi Nobuya helped me with the Japanese judiciary. Carlin Barton straightened me out on certain Latin and Greek names and terms; in doing so she determined that the name of one figure assumed to be from classical Greece in Confessions of a Mask cannot be clarified with certainty. Doris Bargen and Guido Keller helped me with some German terms and expressions.

Gail Malmgreen and Peter Filardo, of Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, found information on Pearl Kluger at the American Committee for Cultural Freedom, Mishimas guide in New York when he visited the United States for the first time, in 1952. Peggy McElveen, Director of Equestrian Programs at Saint Andrews Presbyterian College, answered my equestrian questions. Sakai Tatemi clarified the use of agents in Japan. Takagaki Chihiro enlightened me on certain films. Liza Dalby and Nagasaka Junko imparted some of their deep knowledge on kimono.

Nagasaka Toshihisa went to the Film Center, of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, to see and acquire details on what is left of the 1945 Japanese movie Ware ni tsuzuku o shinzu, one of the films the US Occupation confiscated and did not return to Japan until 1967.

Donald Richie gave me details on Meredith Weatherby, the translator of Confessions of a Mask and The Sound of Waves, and matters related to Mishima in New York, in 1952.

Ron Bayes and Rand Castile told me about their meetings with Mishima. Mr. Bayes, a North Carolina poet laureate, opened for me a path to Mishima Yukio by asking me to translate one of his plays,

Next page