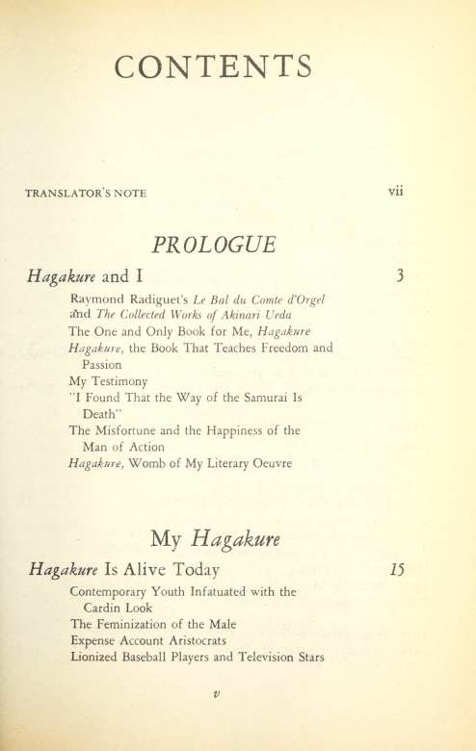

Contents The Compromise Climate of Today, When One May Neither Live Beautifully nor Die Horribly The Ideal Love Is Undeclared Hagakure: Potent Medicine To Soothe the Suffering Soul Suppressed, the Death Impulse Must Eventually Explode Times Have Changed The Significance of Hagakure for the Present The Forty-Eight Vital Principals Of Hagakure and Its Author, Jocho Yamamoto The Background and Composition of Hagakure Jocho and the Transcriber, Tsuramoto Tashiro Hagakure: Three Philosophies The Japanese Image of Death Death According to Hagakure and Death for the Kamikaze Suicide Squadrons

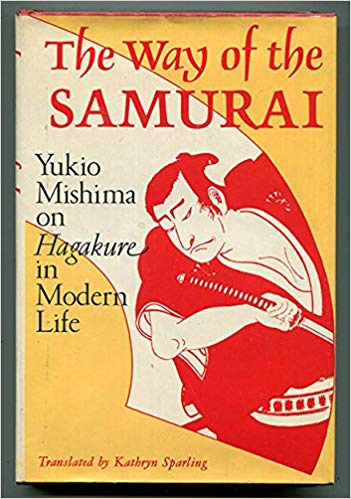

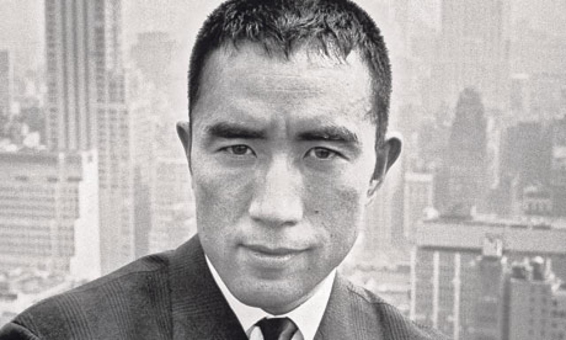

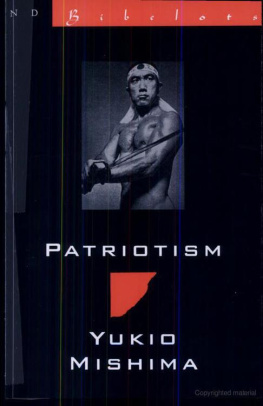

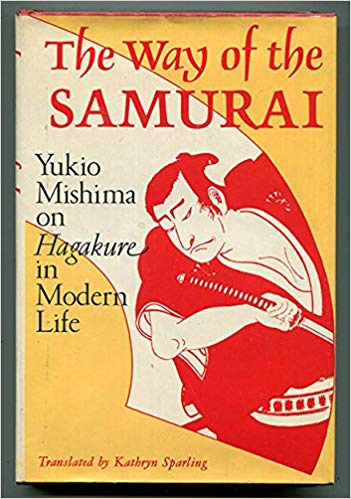

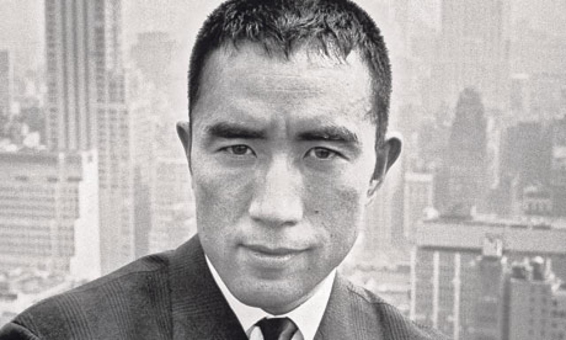

Contents The Compromise Climate of Today, When One May Neither Live Beautifully nor Die Horribly The Ideal Love Is Undeclared Hagakure: Potent Medicine To Soothe the Suffering Soul Suppressed, the Death Impulse Must Eventually Explode Times Have Changed The Significance of Hagakure for the Present The Forty-Eight Vital Principals Of Hagakure and Its Author, Jocho Yamamoto The Background and Composition of Hagakure Jocho and the Transcriber, Tsuramoto Tashiro Hagakure: Three Philosophies The Japanese Image of Death Death According to Hagakure and Death for the Kamikaze Suicide Squadrons  There Is No Distinction Between Chosen Death and Obligatory Death Can One Die for a Just Cause No Death is in Vain Appendix: Selected Words of Wlsdom from Hagakure Day How To Read Hagakure Translator's Note In August 1967, three years before his dramatic ritual suicide at the Self Defense Force Headquarters in Tokyo, Yukio Mishima wrote this fascinating bookhis personal interpretation of the classic samurai ethics and behavior, Hagakure (literally, "Hidden among the Leaves"). Immediately following Mishima's suicide in November, 1970, it became an overwhelming bestseller in Japan. The many who admired him, as well as the otfiers who despised his political positions, turned to Hagakure to help them understand Mishima's final drama. The best known line in the original Hagakure, quoted by many who have never read the work itselr, is: "I have discovered that the Way of the Samurai is death.lhe author continues: "In a htty-htty life or death crisis, simply settle it by choosing immediate death. There is nothing complicated about it. Just brace yourself and proceed....

There Is No Distinction Between Chosen Death and Obligatory Death Can One Die for a Just Cause No Death is in Vain Appendix: Selected Words of Wlsdom from Hagakure Day How To Read Hagakure Translator's Note In August 1967, three years before his dramatic ritual suicide at the Self Defense Force Headquarters in Tokyo, Yukio Mishima wrote this fascinating bookhis personal interpretation of the classic samurai ethics and behavior, Hagakure (literally, "Hidden among the Leaves"). Immediately following Mishima's suicide in November, 1970, it became an overwhelming bestseller in Japan. The many who admired him, as well as the otfiers who despised his political positions, turned to Hagakure to help them understand Mishima's final drama. The best known line in the original Hagakure, quoted by many who have never read the work itselr, is: "I have discovered that the Way of the Samurai is death.lhe author continues: "In a htty-htty life or death crisis, simply settle it by choosing immediate death. There is nothing complicated about it. Just brace yourself and proceed....

One who chooses to go on living having railed in one's mission will be despised as a coward and a bungler. ... In order to be a perfect samurai, it is necessary to prepare oneself for death morning and evening, day in and day out." One of Mishima's many self-images was that of a modern day samurai. It was essential to him that he die while still in his prime and that his death be worthy of the samurai tradition. Even details of the staging of the scene of his death at the Self Defense Force Headquarters show Hagakure influence: The sweatbands worn by Mishima and his companions as he de vn Translator's Note livered his final, passionate address bore a Hagakure slogan. "Men must be the color of cherry blossoms, even in deatn. "Men must be the color of cherry blossoms, even in deatn.

The original Hagakure contains the teachings of the samurai-turned priest Jocho Yamamoto (1659 1719), written down and edited by his student Tsuramoto Tashiro. For generations the manuscript was preserved as moral and practical instruction for the daimyo and samurai retainers in the Nabeshima House of Saga Han in Northern Kyushu. For about one hundred fifty years, until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, however, Hagakure was apparently guarded as secret teachings shown only to a chosen few. The Nabeshima House presumably wanted to keep such valuable, practical instruction to itself. (It is also possible that the intense loyalty to the Nabeshima daimyo advocated in Hagakure might have seemed subversive to the central military government had the manuscript been circulated.) Hagakure became available to the reading public for the first time in the Meiji Era, when its principles of loyalty were reinterpreted in terms of loyalty to the emperor and the Japanese nation. In the nationalistic fervor of the 1930s, several editions and commentaries were published, lavishly extolling Jocho's teachings as yato-d ctshii, "the unique spirit of the Japanese." During the Second World War, editions proliferated and sold in staggering numbers.

I found that the Way of the Samurai is death," became a slogan used to spur young Kamikaze pilots to their deaths. After the war, Hagakure was quickly abandoned as dangerous and subversive. Many copies were destroyed so they would not meet the eyes of the Occupation authorities. Vlll Translator's Note Of course, Hagakure is not merely a book about death. The original is an enormous compilation including moral and practical instruction for samurai, as well as information on local history and the exploits of specific warriors. Mishima deals only with the first three volumes and emphasizes, in addition to death (but not unrelated, of course), action, subjectivity, strength of character, passion, and love (in most cases homosexual love).

He also delights in showing us prolific examples of Jocho's practical advice for daily living: from suggestions on how to hold a meeting, proper behavior at a drinking party, to child rearing, and suppressing a yawn in public. Mishima draws parallels between the moral decay of Jocho's day and that of postwar Japan, explaining how Jocho's advice has helped him live an anachronistic and therefore worthwhile life. Mishima stresses the significant role Hagakure played in his development during the war and after, and discusses similarities between his own criticisms of materialistic postwar Japan and Jocho's criticisms of the sumptuous decadence of his contemporaries. Mishima seems quite close to Jocho in his ideas of personal morality. In their insistence on the spiritual and physical perfection of the self, both men seem to be basically asocial; both are concerned with personal motivation, with how one performs rather than to what effect. Always the emphasis is on the individual, whose ultimate goal is self cultivation rather than contribution to his immediate environment or to society.

Mishima's twist or genius was to apply to modern society the severest social criticism of the samurai ethic found in Hagakure. \ His fiction often deals with the atomization of modern society and the impossibility of spiritual or emotional communication between people. But in Mishima's later works, entwined with the despair of individual isolation, is the exultation of self Translator's Note sufficiency. Everything that interests a Mishima hero he can do by himself. He needs no one, nor does he care what anyone else needs. Such an attitude found ultimate fulfillment in Mishima's death for the sake of an emperor who had no interest in him, for a cause to which he knew he would contribute nothingand by his own hand.

The way toward that violent, yet fascinating death may be found in the pages that follow. KATHRYN SPARLING Columbia University January, 1977 PROLOGUE  Hagakure and I Raymond Radiguet's Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel and The Collected Works of Akinari eda The spiritual companions of youth are friends and books. Friends have flesh-and-blood bodies and are constantly changing. Enthusiasms at one stage in one's life cool with the passage of time, giving way to different enthusiasms shared with a different rnend. In a sense, this is true of books, too. Certainly there are times when a book that has inspired us in our childhood, picked up and reread years later, loses its vivid appeal and seems a mere corpse of the book we remember.

Hagakure and I Raymond Radiguet's Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel and The Collected Works of Akinari eda The spiritual companions of youth are friends and books. Friends have flesh-and-blood bodies and are constantly changing. Enthusiasms at one stage in one's life cool with the passage of time, giving way to different enthusiasms shared with a different rnend. In a sense, this is true of books, too. Certainly there are times when a book that has inspired us in our childhood, picked up and reread years later, loses its vivid appeal and seems a mere corpse of the book we remember.

Next page

Contents The Compromise Climate of Today, When One May Neither Live Beautifully nor Die Horribly The Ideal Love Is Undeclared Hagakure: Potent Medicine To Soothe the Suffering Soul Suppressed, the Death Impulse Must Eventually Explode Times Have Changed The Significance of Hagakure for the Present The Forty-Eight Vital Principals Of Hagakure and Its Author, Jocho Yamamoto The Background and Composition of Hagakure Jocho and the Transcriber, Tsuramoto Tashiro Hagakure: Three Philosophies The Japanese Image of Death Death According to Hagakure and Death for the Kamikaze Suicide Squadrons

Contents The Compromise Climate of Today, When One May Neither Live Beautifully nor Die Horribly The Ideal Love Is Undeclared Hagakure: Potent Medicine To Soothe the Suffering Soul Suppressed, the Death Impulse Must Eventually Explode Times Have Changed The Significance of Hagakure for the Present The Forty-Eight Vital Principals Of Hagakure and Its Author, Jocho Yamamoto The Background and Composition of Hagakure Jocho and the Transcriber, Tsuramoto Tashiro Hagakure: Three Philosophies The Japanese Image of Death Death According to Hagakure and Death for the Kamikaze Suicide Squadrons  There Is No Distinction Between Chosen Death and Obligatory Death Can One Die for a Just Cause No Death is in Vain Appendix: Selected Words of Wlsdom from Hagakure Day How To Read Hagakure Translator's Note In August 1967, three years before his dramatic ritual suicide at the Self Defense Force Headquarters in Tokyo, Yukio Mishima wrote this fascinating bookhis personal interpretation of the classic samurai ethics and behavior, Hagakure (literally, "Hidden among the Leaves"). Immediately following Mishima's suicide in November, 1970, it became an overwhelming bestseller in Japan. The many who admired him, as well as the otfiers who despised his political positions, turned to Hagakure to help them understand Mishima's final drama. The best known line in the original Hagakure, quoted by many who have never read the work itselr, is: "I have discovered that the Way of the Samurai is death.lhe author continues: "In a htty-htty life or death crisis, simply settle it by choosing immediate death. There is nothing complicated about it. Just brace yourself and proceed....

There Is No Distinction Between Chosen Death and Obligatory Death Can One Die for a Just Cause No Death is in Vain Appendix: Selected Words of Wlsdom from Hagakure Day How To Read Hagakure Translator's Note In August 1967, three years before his dramatic ritual suicide at the Self Defense Force Headquarters in Tokyo, Yukio Mishima wrote this fascinating bookhis personal interpretation of the classic samurai ethics and behavior, Hagakure (literally, "Hidden among the Leaves"). Immediately following Mishima's suicide in November, 1970, it became an overwhelming bestseller in Japan. The many who admired him, as well as the otfiers who despised his political positions, turned to Hagakure to help them understand Mishima's final drama. The best known line in the original Hagakure, quoted by many who have never read the work itselr, is: "I have discovered that the Way of the Samurai is death.lhe author continues: "In a htty-htty life or death crisis, simply settle it by choosing immediate death. There is nothing complicated about it. Just brace yourself and proceed.... Hagakure and I Raymond Radiguet's Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel and The Collected Works of Akinari eda The spiritual companions of youth are friends and books. Friends have flesh-and-blood bodies and are constantly changing. Enthusiasms at one stage in one's life cool with the passage of time, giving way to different enthusiasms shared with a different rnend. In a sense, this is true of books, too. Certainly there are times when a book that has inspired us in our childhood, picked up and reread years later, loses its vivid appeal and seems a mere corpse of the book we remember.

Hagakure and I Raymond Radiguet's Le Bal du Comte d'Orgel and The Collected Works of Akinari eda The spiritual companions of youth are friends and books. Friends have flesh-and-blood bodies and are constantly changing. Enthusiasms at one stage in one's life cool with the passage of time, giving way to different enthusiasms shared with a different rnend. In a sense, this is true of books, too. Certainly there are times when a book that has inspired us in our childhood, picked up and reread years later, loses its vivid appeal and seems a mere corpse of the book we remember.