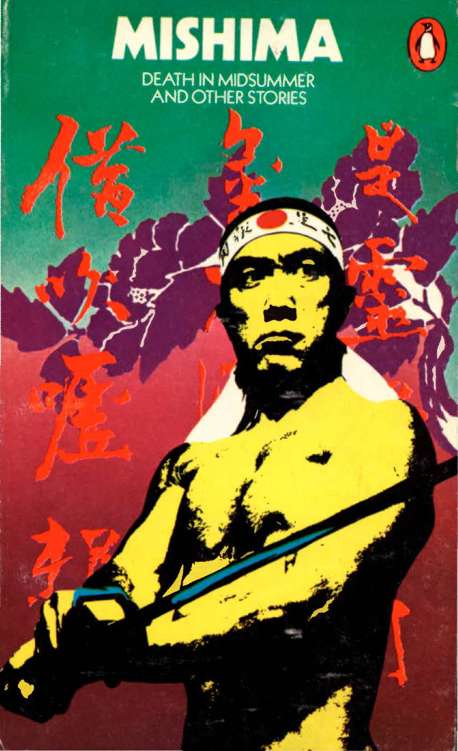

Yukio Mishima

Death in Midsummer

and Other Stories

Penguin Books

in association with Martin Seeker & Warburg Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth,

Middlesex, England

Penguin Books, 625 Madison Avenue,

New York, New York 10022, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood,

Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 41 Steelcase Road West, Markham, Ontario, Canada

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published in the U.SJL 1966

Published in Great Britain by Martin Seeker & Warburg 1907

Published in Penguin Books 1971

Reprinted 1977

Copyright New Directions, 1966

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Cox & Wyman Ltd, London, Reading and Fakenham Set in Intertype Times

Some of these stories have appeared previously in Cosmopolitan, Esquire,Harper's Bazaai, Japan Quarterly, and Today's Japan. The Priest of Shiga Temple and His Love' was published in the UNESCO collection ModemJapanese Stories by Eyre & Spottiswoode This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of landing or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

To Philippe and Pauline de Rothschild

Contents

Death in Midsummer 9

Three Million Yen 39

Thermos Flasks 52

The Priest of Shiga Temple and His Love 68

The Seven Bridges 85

Patriotism 102

Dojoji 128

Onnagata 145

The Pearl 168

Swaddling Clothes 181

Death in Midsummer

La mort... nous affecte plus profondement sous le rbgnepompeux de I'ete.

Baudelaire: Les Paradis Artificiels

A. Beach, near the southern tip of the Izu Peninsula, is still unspoiled for sea bathing. The sea bottom is pitted and uneven, it is true, and the surf is a little rough; but the water is clean, the slope out to sea is gentle, and conditions are on the whole good for swimming. Largely because it is so out of the way, A. Beach has none of the noise and dirt of resorts nearer Tokyo. It is a two-hour bus ride from Ito.

Almost the only inn is the Eirakuso, which also has cottages to rent. There are only one or two of the shabby refreshment stands that clutter most beaches in summer. The sand is rich and white, and half-way down the beach a rock, surmounted by pines, crouches over the sea almost as if it were the work of a landscape gardener. At high tide it lies half under water.

And the view is beautiful. When the west wind blows the mists from the sea, the islands off shore come in sight, Oshima near at hand and Toshima farther off, and between them a little triangular island called Utoneshima. Beyond the headland of Nanago lies Cape Sakai, a part of the same mountain mass, throwing its roots deep into the sea; and beyond that the cape known as the Dragon Palace of Yatsu, and Cape Tsumeki, on the southern tip of which a lighthouse beam revolves each night.

In her room at the Eirakusd Tomoko Ikuta was taking a nap. She was the mother of three children, though one would never have suspected it to look at the sleeping figure. The knees showed under the one-piece dress, just a little short, of light salmon-pink linen. The plump arms, the unworn face, and the slightly curled hps gave off a girl-like freshness. Perspiration had come out on the forehead and in the hollows beside the nose. Flies buzzed dully, and the air was like the inside of a 9

heated metal dome. The salmon linen rose and fell so slightly that it seemed the embodiment of the heavy, windless afternoon.

Most of the other guests were down on the beach. Tomoko's room was on the second floor. Below her window was a white swing for children. There were chairs on the lawn, as well as tables and a peg for quoits. The quoits lay scattered over the lawn. No one was in sight, and the buzzing of an occasional bee was drowned out by the waves beyond the hedge. The pines came immediately up to the hedge, and gave way beyond to the sand and the surf. A stream passed under the inn. It formed a pool before spilling into the ocean, and fourteen or fifteen geese would splash and honk most indelicately as they fed there every afternoon.

Tomoko had two sons, Kiyoo and Katsuo, who were six and three, and a daughter, Keiko, who was five. All three were down on the beach with Yasue, Tomoko's sister-in-law.

Tomoko felt no qualms about asking Yasue to take care of the children while she had a nap herself.

Yasue was an old maid. In need of help after Kiyoo was born, Tomoko had consulted her husband and decided to invite Yasue in from the provinces. There was no real reason why Yasue had remained unmarried. She was not particularly alluri ing, indeed, but then neither was she homely. She had declined proposal after proposal, until she was past the age for marrying.

Much taken with the idea of following her brother to Tokyo, she leaped at Tomoko's invitation. Her family had plans for marrying her off to a provincial notable.

Yasue was far from quick, but she was very good-natured.; She addressed Tomoko, younger than she, as an older sister, and was always careful to defer to her. The Kanazawa accent had almost disappeared. Besides helping with the children and the housework, Yasue went to sewing school and made clothes for herself, of course, and for Tomoko and the children too.

She would take out her notebook and sketch new fashions in downtown shop windows, and sometimes she would find a shop-girl glaring at her and even reprimanding her.

She was down on the beach in a stylish green bathing suit.

This alone she had not made - it was from a department store.

Ver

11 y proud of her fair north-country skin, she showed hardly a trace of sunburn. She always hurried from the water back to her umbrella. The children were at the edge of the water building a sand castle, and Yasue amused herself by dripping the watery sand on her white leg. The sand, immediately dry, fell into a dark pattern, sparkling with tiny shell fragments. Yasue hastily brushed at it, as if from a sudden fear that it would not wash off. A half-transparent little insect jumped from the sand and scurried away.

Stretching her legs and leaning back on her hands, Yasue looked out to sea. Great cloud masses boiled up, immense in their quiet majesty. They seemed to drink up all the noise below, even the sound of the sea.

It was the height of summer and there was anger in the rays of the sun.

The children were tired of the sand castle. They ran off kick*

ing up the water in the shallows. Startled from the safe little private world into which she had slipped, Yasue ran after them.

But they did nothing dangerous. They were afraid of the roar of the waves. There was a gentle eddy beyond the line where the waves fell back. Kiyoo and Keiko, hand* in hand, stood waist-deep in the water, their eyes sparkling as they braced against the water and felt the sand at the soles of their feet.

'Like someone's pulling,' said Kiyoo to his sister.

Yasue came up beside them and warned them not to go in any deeper. She pointed at Katsuo. They shouldn't leave him there alone, they should go up and play with him. But they paid no attention to her. They stood hand in hand, smiling happily at each other. They had a secret all their own, the feel of the sand as it pulled away from their feet.

Yasue was afraid of the sun. She looked at her shoulder and her breasts, and she thought of the snow in Kanazawa. She gave herself a little pinch high on the breast. She smiled at the warmth. The nails were a little long and there was sand under them - she would have to cut them when she got back to her room.

Next page