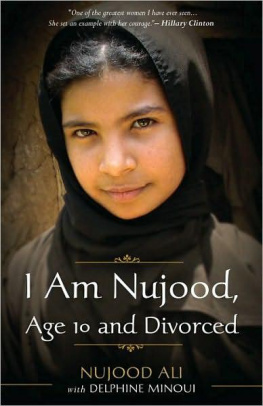

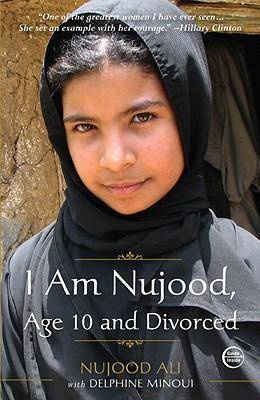

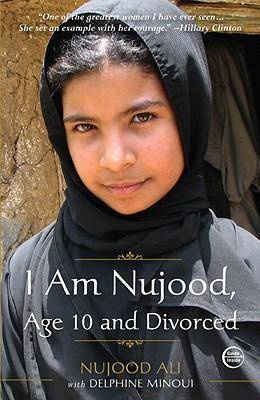

Nujood Ali, Delphine Minoui

I Am Nujood, Age 10 and Devorced

Translation copyright 2010 by Nujood Ali and Delphine Minoui

Nujood, a Modern-Day Heroine

Once upon a time there was a magical land with legends as astonishing as its houses, which are adorned with such delicate tracery that they look like gingerbread cottages trimmed with icing. A land at the southernmost tip of the Arabian Peninsula, washed by the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. A land steeped in a thousand years of history, where adobe turrets perch on the peaks of serried mountains. A land where the scent of incense wafts gaily around the corners of the narrow cobblestone streets.

This country is called Yemen.

But a very long time ago, grown-ups gave it another name: Arabia Felix, Happy Arabia.

For Yemen inspires dreams. It is the realm of the Queen of Sheba, an incredibly strong and beautiful woman who inflamed the heart of King Solomon and left her mark in the sacred pages of the Bible and the Koran. It is a mysterious place where men never appear in public without curved daggers worn proudly at their waists, while women hide their charms behind thick black veils.

It is a land that lies along an ancient trade route, a country crossed by merchant caravans laden with fine fabrics, cinnamon, and other aromatic spices. These caravans journeyed on for weeks, sometimes months, never stopping, persevering through wind and rain, and the weakest travelers, the stories say, never came home again.

To see Yemen in your minds eye, imagine a country a little larger than Syria, Greece, and Nepal all rolled into one, and diving headlong into the Gulf of Aden. Out there, in those tempestuous seas, pirates from many lands lie in wait for merchant ships plying their trades in India, Africa, Europe, and America.

In centuries past, many invaders succumbed to the temptation to claim this lovely land for themselves. Ethiopians came ashore armed with their bows and arrows, but were swiftly driven away. Next came the Persians, with their bushy eyebrows, who constructed canals and fortresses and recruited various native tribes to fight off other invaders. The Portuguese then tried their luck, and set up trading outposts. The Ottomans, who later took up the challenge, held sway in the country for more than a hundred years. Still later, the British, with their white skin, put into port in the south, in Aden, while the Turks set up shop in the north. And then, once the English were gone, Russians from colder climes set their sights upon the south. Like a cake fought over by greedy children, the country gradually split in two.

Grown-ups say that this Arabia Felix has always been the object of envious desire because of its thousand and one treasures. Foreigners covet its oil; its honey is worth its weight in gold; the music of Yemen is captivating, its poetry gentle and refined, its spicy cuisine endlessly pleasing. From around the world, archeologists come to this country to study the architecture of its ruins.

It has been years and years now since the invaders packed up their bags and left, but ever since their departure, Yemen has experienced a series of civil wars too complicated for the pages of childrens books. Unified in 1990, the nation still suffers from the wounds left by these many conflicts, like a sick old man, trying to get well, who has lost his bearings and must learn to walk again. Sometimes you even wonder who makes the law in this strange land, where many girls and boys beg in the streets instead of going to school.

Yemens head of state is a president whose photograph often decorates the display windows of shops, but power in this country lies also with tribal chiefs in turbans who wield enormous authority in the villages, whether its a question of arms sales, marriage, or the commerce and culture of khat. Then there are those explosions in the capital, Sanaa, in the chic neighborhoods where the diplomatic representatives of foreign nations live, people who drive big cars with tinted windows. And in Yemeni homes, of course, the real law is laid down by fathers and older brothers.

It was in this extraordinary and turbulent country, barely ten years ago, that a little girl named Nujood was born.

A tiny wisp of a thing, Nujood is neither a queen nor a princess. She is a normal girl with parents and plenty of brothers and sisters. Like all children her age, she loves to play hide-and-seek and adores chocolate. She likes to make colored drawings and fantasizes about being a sea turtle, because she has never seen the ocean. When she smiles, a tiny dimple appears in her left cheek.

One cold and gray February evening in 2008, however, that appealing and mischievous grin suddenly melted into bitter tears when her father told her that she was going to wed a man three times her age. It was as if the whole world had landed on her shoulders. Hastily married off a few days later, the little girl resolved to gather all her strength and try to escape her miserable fate

DELPHINE MINOUI

April 2, 2008

My head is spinning-Ive never seen so many people in my whole life. In the yard outside the courthouse, a crowd is bustling around in every direction: men in suits and ties with bunches of yellowed files tucked under their arms; other men wearing the zanna, the traditional ankle-length tunic of the villages of northern Yemen; and then all these women, shouting and weeping so loudly that I cant understand a word.

Id love to read their lips to find out what theyre saying, but the niqabs that match their long black robes hide everything except their big, round eyes. The women seem furious, as if a tornado had just destroyed their houses. I try to listen closely.

I can catch only a few words-childcare, justice, human rights-and Im not really sure what they mean. Not far away from me is a broad-shouldered giant wearing his turban jammed down to his eyes; hes carrying a plastic bag full of documents and telling anyone who will listen that he has come here to try to get back some land that was stolen from him. Hes dashing around like a frantic rabbit, and he almost runs right into me.

What chaos It must be like Al-Qa Square, the one in the heart of Sanaa where out-of-work laborers go, the place Aba-Papa-often talks about. There its every man for himself, and they all want to be the first to snag a job for the day at dawn, just after the first azaan, the traditional summons to prayer called out five times a day by the muezzins from the minarets of their mosques. Poor people are so hungry theyve got stones where their hearts should be, and no time to feel pity for the fates of others. Still, Id like so much for someone here to take my hand, to look at me with kindness. Wont anyone listen to me, for once? Its as if I were invisible. No one sees me: Im too small for them; I barely come up to their tummies. Im only ten years old, maybe not even that. Who knows?

Id imagined the courthouse differently: a calm, clean place, the great house where Good battles Evil, where you can fix all the problems of the world. Id already seen some courtrooms on my neighbors television, with judges in long robes. People say theyre the ones who can help people in need. So I have to find one and tell him my story. Im exhausted. Its hot under my veil, I have a headache, and Im so ashamed Am I strong enough to keep going? No. Yes. Maybe I tell myself its too late to turn back; the hardest part is over, and I have to go on.

When I left my parents house early this morning, I promised myself not to set foot there again until Id gotten what I wanted.

Next page