To all those who fight for justice

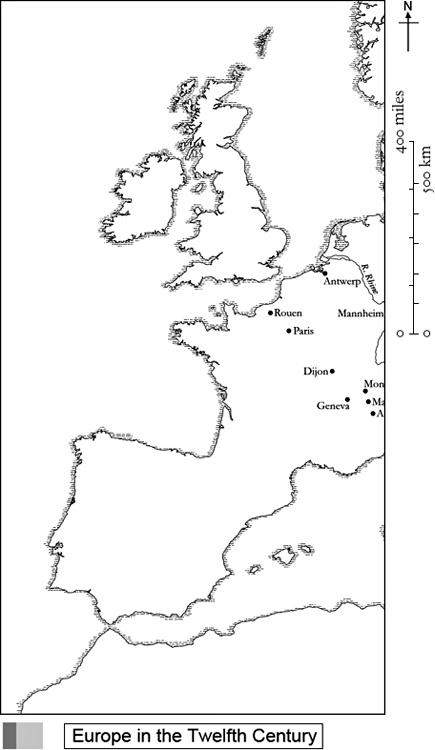

MAP I

England in the Twelfth Century

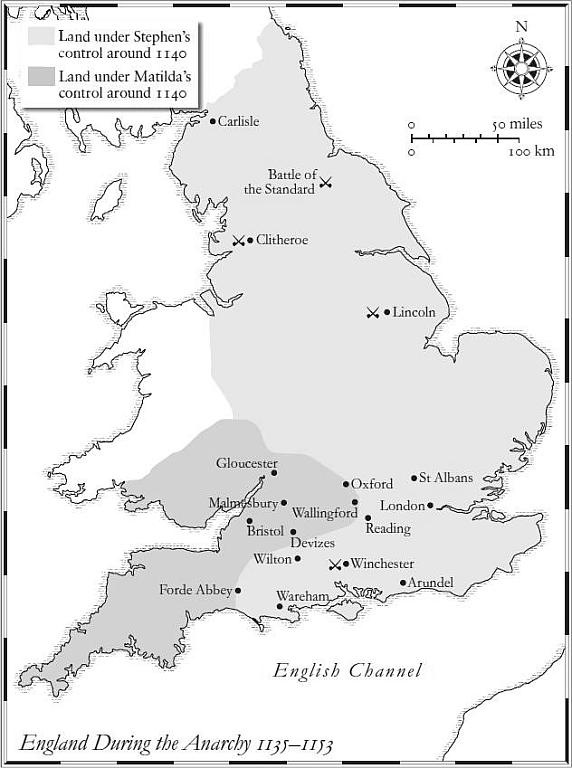

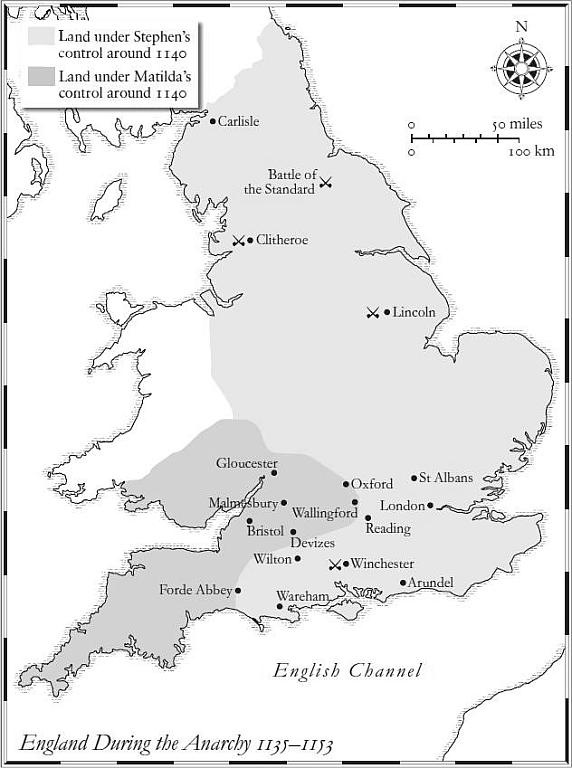

MAP II

England during the Anarchy, 11351153

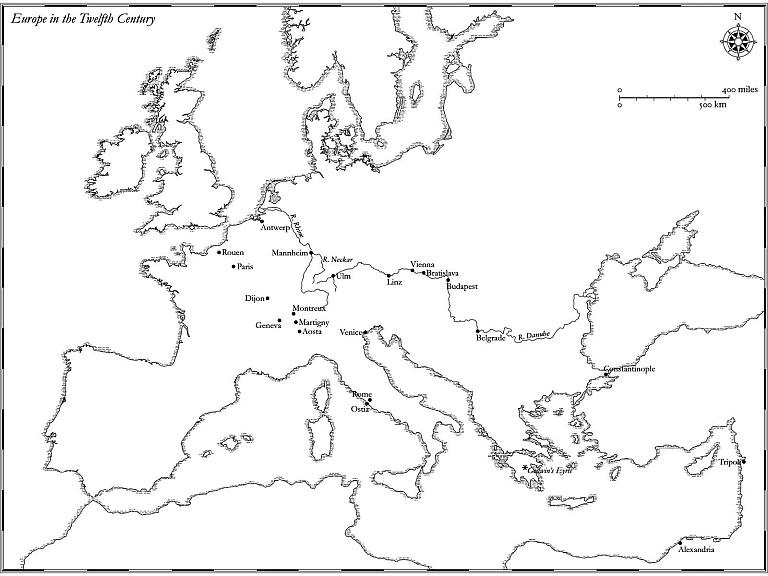

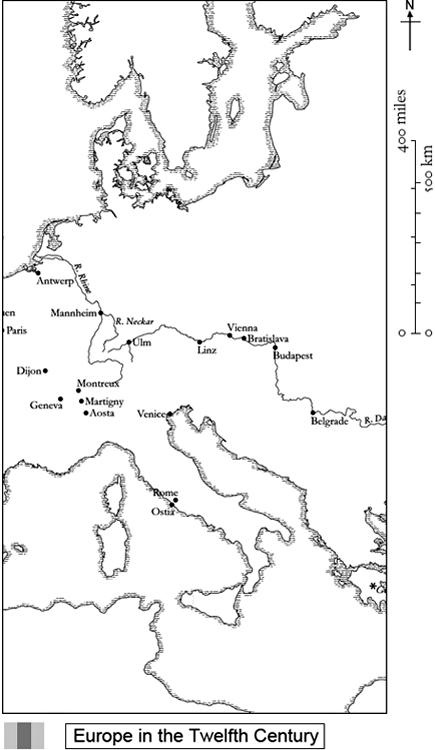

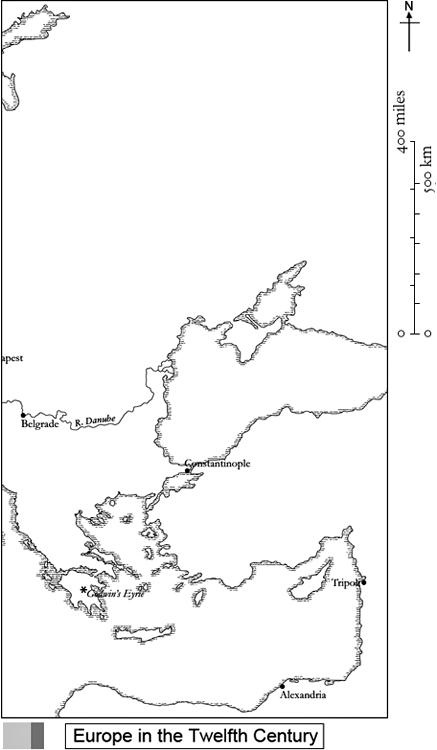

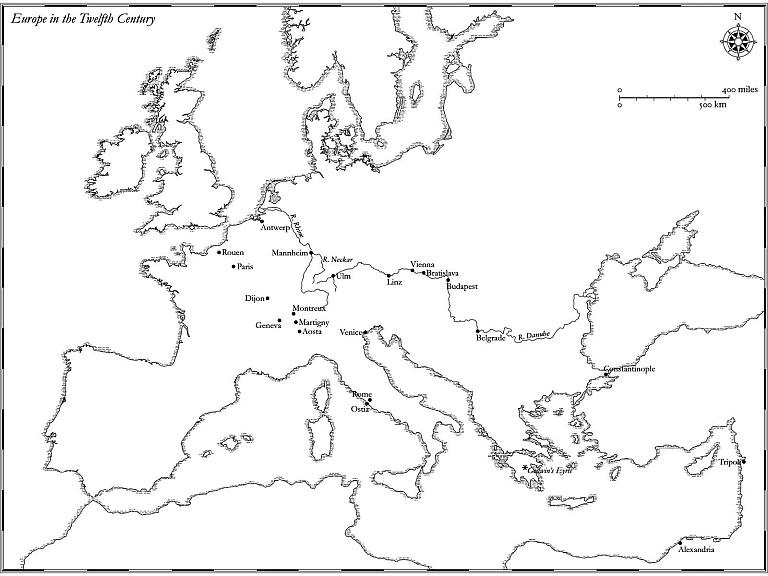

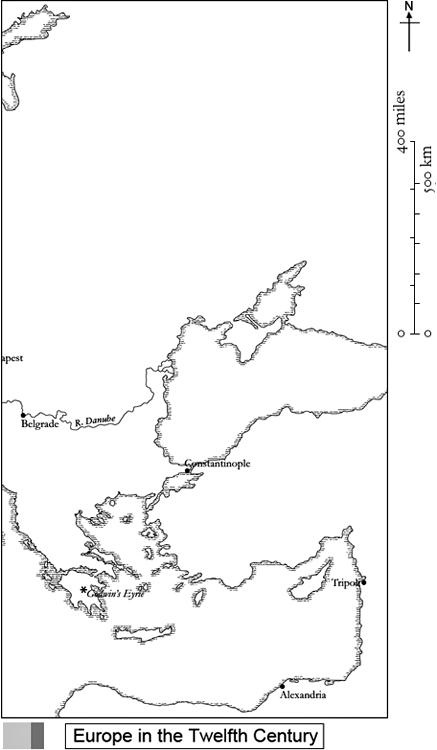

MAP III

Europe in the Twelfth Century

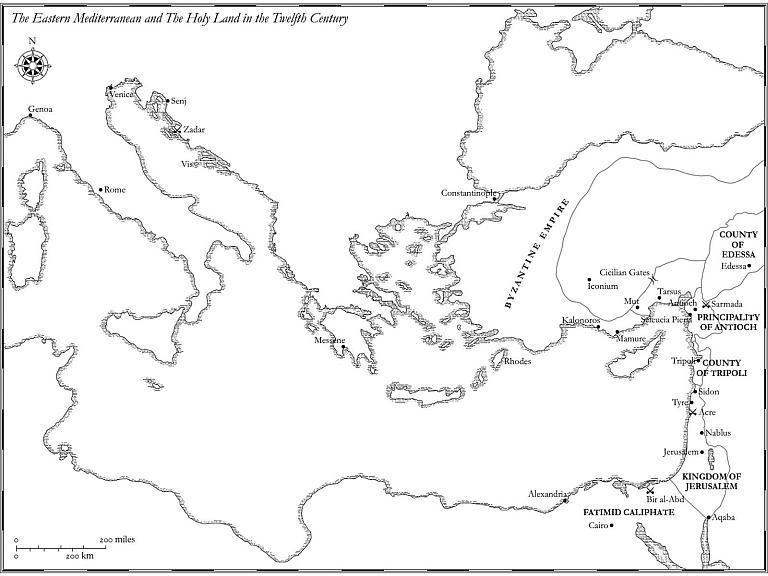

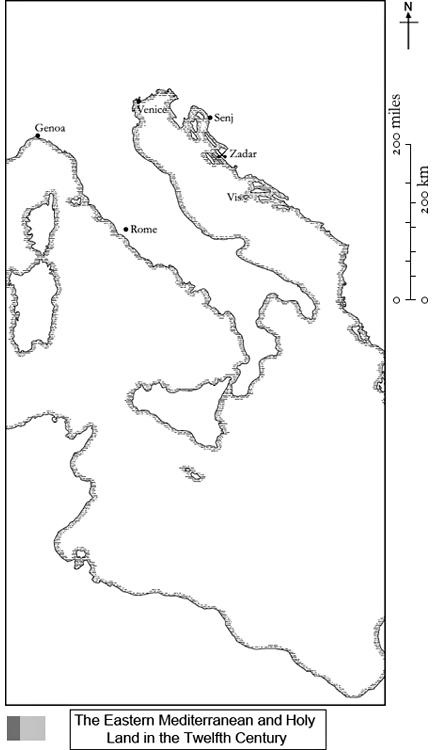

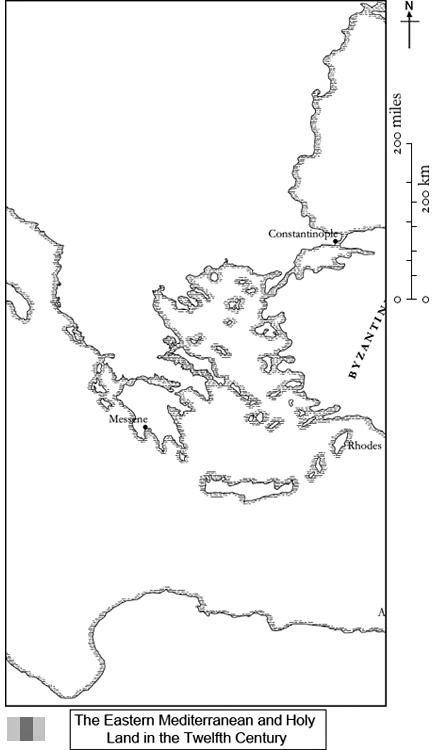

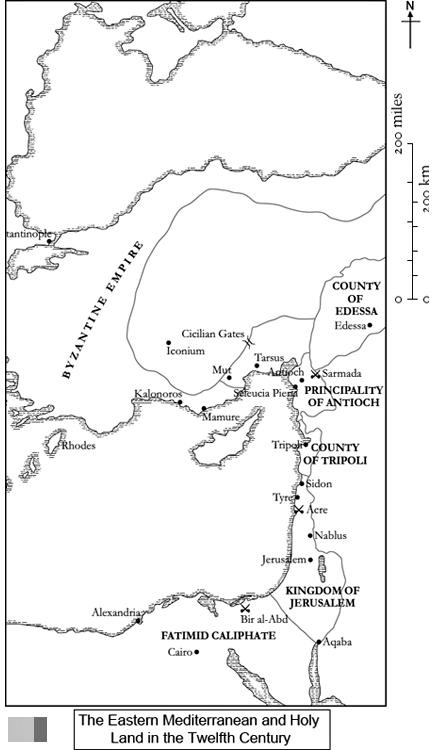

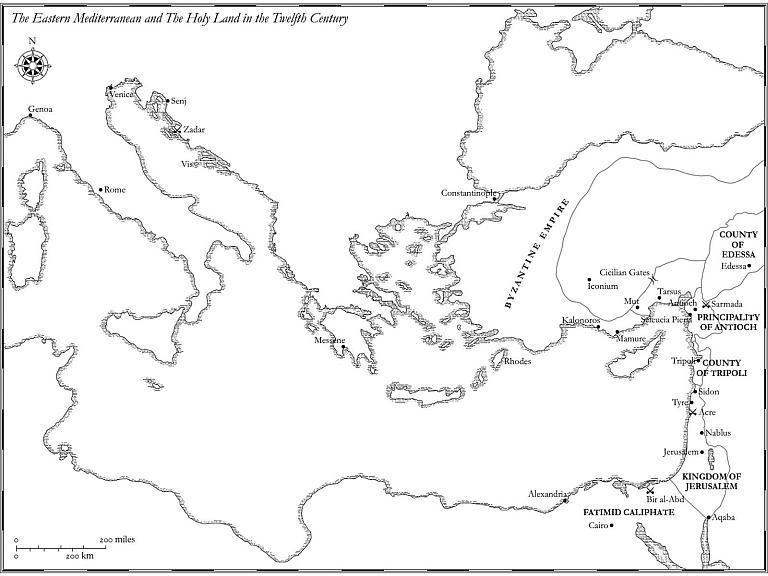

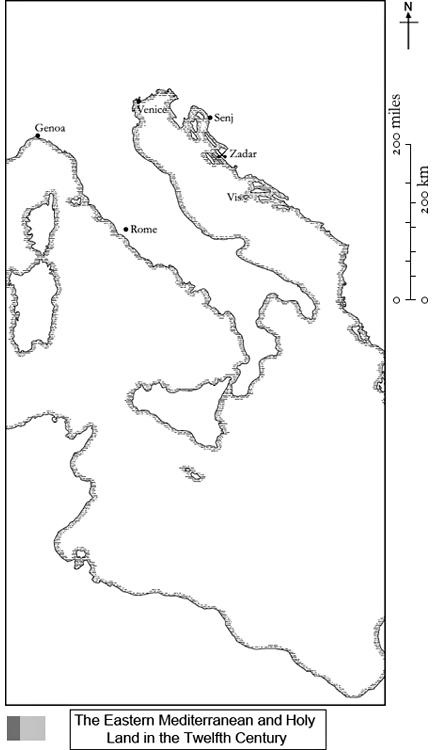

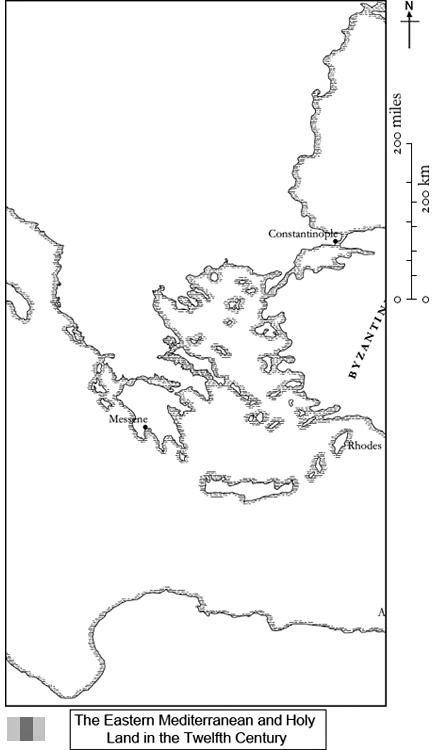

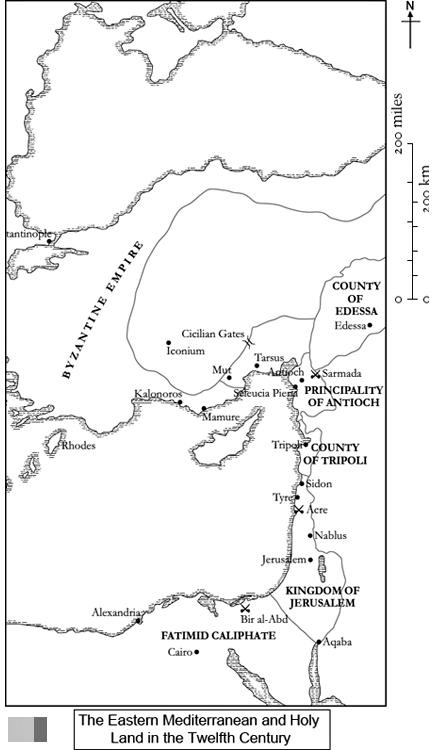

MAP IV

The Eastern Mediterranean and Holy Land in the Twelfth Century

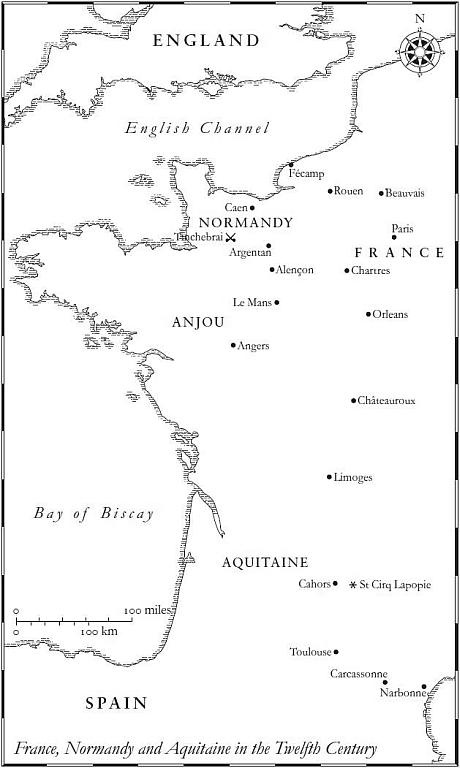

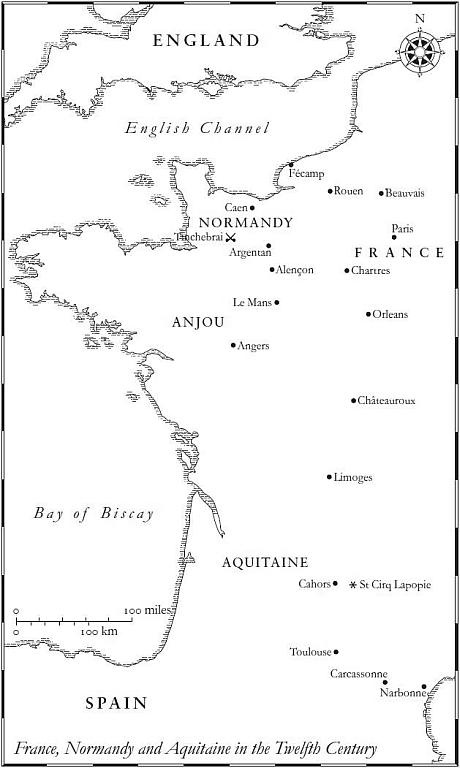

MAP V

France, Normandy and Aquitaine in the Twelfth Century

When Henry Beauclerc, King of England and Duke of Normandy, died in 1135, the powerful Norman dynasty that had conquered England in 1066 still held the English and its own Norman heartland in the iron gauntlet of its daunting rule. Henry was the fourth son of his formidable father, William the Bastard, Conqueror of the English. Henry had grabbed the English throne when his elder brother, William Rufus, was killed by an arrow while hunting in the New Forest in 1100. He then seized the Dukedom of Normandy from his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, who had been fighting in the First Crusade when Rufus died. Henry defeated Robert at the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106 and imprisoned him for almost thirty years until he died in Cardiff Castle, in 1134.

There was little room for brotherly love in the harsh world of Norman kings.

Henry Beauclerc ruled his domain as came to be expected of a Norman warlord: efficiently and harshly. The conquered English had been cowed into submission by their ruthless Norman masters, but bitter resentment lay not far beneath the surface.

Henry produced a huge brood of children by almost as many women, but only two of them were legitimate. His second child, William Adelin, was groomed to be his successor: he would be William II, his mighty grandfathers namesake. But William was drowned in the disaster of the White Ship in 1120. Carelessly, Henry was left without a male heir and, try as he might, he could not produce a replacement for William even with a young and fertile second wife. He turned to his firstborn, his daughter, Matilda, who he had already married off to Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor. But she was also childless.

Then fate played an unexpected card: Henry V died suddenly in 1125, making it possible for the Empress Matilda to marry again and give Henry his grandson and heir. Geoffrey, the son of the Count of Anjou, a handsome young man who would bring Normandy an important strategic alliance as well as the fruits of his loins, was chosen. Henry was delighted, but not so Matilda: Geoffrey was only fourteen years old, Matilda was twenty-five. The marriage was not happy and the Kings anticipated heir did not appear. But Henry was patient and named Matilda as his successor in the hope that a grandson would eventually be conceived and that Matilda would act as Queen Regent until the boy was old enough to inherit.

Two years before his death, Henry Beauclercs patience was rewarded when Matilda gave birth to a son. Dutifully, she called the boy Henry In her fathers honour. All seemed well, but all was not well: what appeared to be a happy conclusion to a crisis of succession was just the beginning of a tragic tale. Matilda was not only the daughter of a Norman king, she was also the daughter of Edith, a Scottish princess. Edith not only carried Celtic royal blood but, through her mother, Margaret, was a direct descendent of the vanquished kings of England. Thus, the Empress Matilda and her baby son embodied the hopes not only of a Norman dynasty, but also of every Celt and Englishman.

When King Henry died in 1135, fate dealt another rogue card. Matildas cousin, Stephen of Blois, the son of Adela William the Conquerors youngest daughter and the ninth child of his large brood emulated his uncle Henrys audacious move in 1100 and dashed across the Channel to grab the English crown.

But fate had also played a third card: a wild one, a joker, which changed the game completely. It brought another family into the saga, an English family not one of royal pedigree, but one that had already played a crucial role in Englands destiny and could trace its lineage back to a man whose heroic deeds were almost lost in legend: the mighty Hereward of Bourne.

Chaos followed Stephen of Blois impudent move in 1135, not just a short interlude of dynastic warfare, but a long and bitter feud that lasted almost twenty years and brought England and Normandy to their knees. So terrible were the times that the chroniclers called them The Anarchy.

One such chronicler was Gilbert Foliot, one of the great minds of twelfth-century Europe. Born into an ecclesiastical family in Normandy in 1110, he entered the great Abbey of Cluny at the age of twenty. A typically ambitious and determined member of the Norman elite which ruled England after the Conquest of 1066, he became Abbot of Gloucester in 1139, Bishop of Hereford in 1148 and Bishop of London in 1163. He was thus witness to one of the most tumultuous periods in English history: the Anarchy of Stephen and Matilda, the troubled reign of the mighty Henry Plantagenet and the trauma of the murder of Thomas Becket. Fluent in French, English and Latin, he was the most prolific letter-writer of his age; almost 300 of his letters have survived into modern times.

As a young man at Cluny, Gilbert befriended Thibaud de Vermandois. It was an amity that would last a lifetime. Vermandois became Abbot of Cluny in 1180 and when Pope Lucius III named him Cardinal Bishop of Ostia e Velletri the ancient port of Rome and a sub-diocese of the Bishopric of Rome in 1184, he became one of the most powerful men in the Church and signatory of all Papal Bulls.

In 1186, Foliot, who was now almost blind, increasingly frail with old age and fearing his imminent death, felt compelled to begin a long series of letters to Vermandois.

This is the story of the turbulent events he chronicled.

Fulham Palace, 1 September 1186

My Dearest Thibaud,

Forgive me, perhaps I should not be so familiar now that you wear the blue cape of a cardinal of Rome. I imagine it tempts ones vanity to be addressed as Eminence. I am accorded Lord Bishop, which is quite enough for the son of a steward, although I have been greeted as Beatitude a few times and even Holiness on one famous occasion in front of the entire Chapter of St Pauls, which found it difficult to contain itself for several minutes.