Quelle que soit la dure de votre sjour sur cette petite plante, et quoi quil vous advienne, le plus important cest que vous puissiez de temps en temps sentir la caresse exquise de la vie.

(However long your stay on this small planet lasts, and whatever happens during it, the most important thing is that from time to time you feel lifes sweet caress.)

Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, Avis de passage (1957)

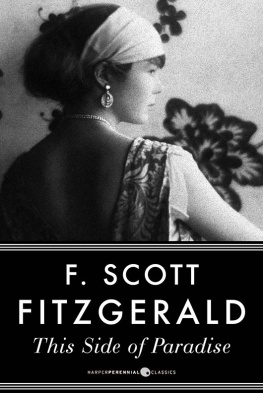

Amory Clay in 1928.

What drew me down there, I wonder, to the edge of the garden? I remember the summer light the trees, the bushes, the grass luminously green, basted by the bland, benevolent late-afternoon sun. Was it the light? But there was the laughter, also, coming from where a group of people had gathered by the pond. Someone must have been horsing around making everyone laugh. The light and the laughter, then.

I was in the house, in my bedroom, bored, with the window open wide so I could hear the chatter of conversation from the guests and then the sudden arpeggio of delighted laughter came that made me slip off my bed and go to the window to see the gentlemen and ladies and the marquee and the trestle tables laid out with canaps and punchbowls. I was curious why were they all making their way towards the pond? What was the source of this merriment? So I hurried downstairs to join them.

And then, halfway across the lawn, I turned and ran back to the house to fetch my camera. Why did I do that? I think I have an idea, now, all these years later. I wanted to capture that moment, that benign congregation in the garden on a warm summer evening in England; to capture it and imprison it forever. Somehow I sensed I could stop times relentless motion and hold that scene, that split second with the ladies and the gentlemen in their finery, as they laughed, careless and untroubled. I would catch them fast, eternally, thanks to the properties of my wonderful machine. In my hands I had the power to stop time, or so I fancied.

THERE WAS A MISTAKE MADE on the day I was born, when I come to think of it. It doesnt seem important, now, but on 7 March 1908 such a long time ago, it seems, threescore years and ten almost it made my mother very cross. However, be that as it may, I was born and my father, sternly instructed by my mother, placed an announcement in The Times. I was their first child, so the world the readers of the London Times was duly informed. 7 March 1908, to Beverley and Wilfreda Clay, a son, Amory.

Why did he say son? To spite his wife, my mother? Or was it some perverse wish that I wasnt in fact a girl, that he didnt want to have a daughter? Was that why he tried to kill me later, I wonder. .? By the time I came across the parched yellow cutting hidden in a scrapbook, my father had been dead for decades. Too late to ask him. Another mistake.

Beverley Vernon Clay, my father but no doubt best known to you and his few readers (most long disappeared) as B. V. Clay. A short-story writer of the early twentieth century stories mainly of the supernatural sort failed novelist and all-round man of letters. Born in 1878, died in 1944. This is what the Oxford Companion to English Literature (third edition) has to say about him:

Clay, Beverley Vernon

B. V. Clay (18781944). Writer of short stories. Collected in The Thankless Task (1901), Malevolent Lullaby (1905), Guilty Pleasures (1907), The Friday Club (1910) and others. He wrote several tales of the supernatural of which The Belladonna Benefaction is best known. This was dramatised by Eric Maude (q.v.) in 1906 and ran for over three years and 1,000 performances in the West End of London (see Edwardian Theatre).

Its not much, is it? Not many words to summarise such a complicated, difficult life, but then its more than most of us will receive in the various annals of posterity that record our brief passage of time on this small planet. Funnily enough, I was always confident nothing would ever be written about me, B. V. Clays daughter, but it turned out I was wrong. .

Anyway, I have memories of my father in my very early childhood but I feel I only began to know him when he came back from the war the Great War, the 191418 war when I was ten and, in a way, when I was already well down the road to becoming the person and the personality that I am today. So it was different having that gap of time that the war imposed, and everyone has since told me he was also a different man himself, when he came back, irrevocably changed by his experiences. I wish I had known him better before that trauma and who wouldnt want to travel back in time and encounter their parents before they become their parents? Before mother and father turned them into figures of domestic myth, forever trapped and fixed in the amber of those appellations and their consequences?

The Clay family.

My father: B. V. Clay.

My mother: Wilfreda Clay (ne Reade-Hill) (b.1879).

Me: Amory, firstborn. A girl (b.1908).

Sister: Peggy (b.1914).

Brother: Alexander, always known as Xan (b.1916).

The Clay family.

*

THE BARRANDALE JOURNAL 1977

I was driving back to Barrandale from Oban in the evening in the haunted gloaming of a Scottish summer when I saw a wild cat pick its way across the road, not 200 yards from the bridge to the island. I stopped the car at once and switched off the engine, watching and waiting. The cat halted its deliberate progress and turned its head to me, almost haughtily, as if Id interrupted it. I reached, without thinking, for my camera my old Leica and held it up to my eye. Then put it down. There are no photographs more boring than photographs of animals discuss. I watched the brindled cat the size of a cocker spaniel finish its pedantic traverse of the road and slip into the new conifer plantation, promptly becoming invisible. I started the engine and drove on home to the cottage, strangely exhilarated.

I call it the cottage, however its true postal designation is 6 Druim Rigg Road, Barrandale Island. As to where numbers 15 are, I have no idea, because the cottage sits alone on its small bay and Druim Rigg Road ends with it. Its a solid, two-storey, thick-walled, mid-nineteenth-century, small-roomed house with two chimney stacks and one-storey outbuildings attached on either side. I assumed somebody farmed here a hundred years ago, but all thats gone, now. It has mossy tiled roofs and walls of concrete cladding that had aged to an unpleasant, bilious grey-green and that I had painted white when I moved in.

It fronted the small, unnamed bay and if you turned left, west, you could see the southern tip of Mull and the wind-worked grey expanse of the vast Atlantic beyond.

I came in the front door and Flam, my dog, my black Labrador, gave his one glottal bass bark of welcome. I put away my shopping and then went through to the parlour, my sitting room, to check on the fire. I had a big stove with glass doors set in the chimney recess in which I burned peat bricks. The fire was low so I threw some bricks on it. I liked the concept of burning peat, rather than coal as if I were burning ancient landscapes, whole eons, whole geographies were turning into ash as they heated my house, heated my water.

The cottage on Barrandale Island, before renovations and repainting, c.1960.