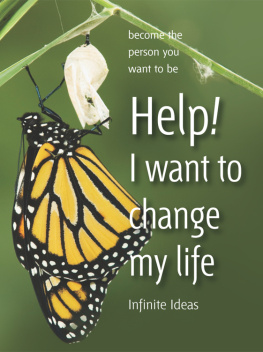

Lessons on Change,

Loss, and Spiritual

Transformation

Broadway Books New York

LETTING GO OF

THE PERSON YOU

USED TO BE

Lama Surya Das

Contents

To the long life of the Dalai Lama and

the freedom and well-being of

the people of Tibet

Introduction:

Gaining Through Loss

W herever I go lately, people ask how I deal with fear, anger, and pain; they want advice on healing painful wounds caused by trauma and shock in their lives. It seems as though I am speaking and writing constantly about the need for learning to grieve, to learn the lessons, to let go and forgive and move on; and for prayerful reflection, more historical learning, and cross-cultural global perspectives. Many of us are seeking a common ground and higher spiritual principles to adhere to during troubled times. I firmly believed that deep down everyone truly wants peaceful coexistence in this world in our lifetime. But we must first learn how to deal with anger and hatred in ourselves, to soften and disarm our own hearts, before we can effectively work to resolve conflicts and create peace with others.

Many men and women are reeling emotionally from recent traumas, whether these traumas represent personal disappointment and loss or global chaos. Too frequently, the common advice we hear for dealing with our feelings of grief and pain falls short of really helping. Retaliation, revenge, and anger, while they might seem initially satisfying, are not the answers. Neither are despair and helplessness. But there is a middle-way approach, in which suffering can be transformed into understanding, compassion, wisdom, and even peace. This is possible for all of us if we apply ourselves to such a transformation, no matter who we are, where we live, or what we believe. Reverend Martin Luther King said that we have only two choices: to live together as brothers or perish together as fools. It is inevitably in our higher self-interest to pull together, if we don't want to be pulled apart.

Buddha taught that without any difficulties and problems, we cannot really grow in inner strength, patient forbearance, emotional maturity, and vision. Everything changes, yet what is most true and real always remains. This has been brought home to me in recent years. I have learned that If you truly want to grow as a person and learn, you should realize that the universe has enrolled you in the graduate program of life, called loss, as Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross says.

There is a story about a seeker who travels to the Himalayas, looking for an enlightened Buddha in order to receive personal teachings. This seeker wants the last word on the subject of enlightenment. Walking and trekking for days, he begins to drop his heavy gear as he makes his way to the top of a high peak in Nepal. He drops his tent, his camping equipment, and his heavy backpack. Stripped of almost everything and having breathed so many hundreds of thousands of breaths, he has finally forgotten about his worldly preoccupations. He is very ready to arrive and very ready to listen. He pulls himself up over the final rim of the mountain and looks into the mouth of a cave. Amazingly enough, the Buddha-like master is sitting right there. Stunned, relieved, and overjoyed, the seeker asks the Sage, What is the first principle? What is your most important truth and teaching?

The seeker thinks this is going to be his big moment and that he is about to become enlightened. He is going to discover the one essential thing for him to ponder. And then the Buddha replies: Dukkha. Life is suffering, life is fraught, life is difficult. And the seeker is totally disappointed! He looks around wildly and shouts, Is there anyone else up here that I can talk to?!!

I love that story. What do we do when we experience something that isn't quite what we had hoped for, or worse, when we experience something that is truly difficult? Fortunately, within the Buddhist canon there are many wonderful teachings that provide guidance for us. The teachings help us deal intelligently with loss, change, and fear; they help us with the big questions, like the meaning of life and the keys to happiness; and they teach us about death and suffering, and how to utilize everything as grist for the mill and as the means for transformation.

A Buddhist wise guy's rendition of the First Noble Truth of dukkha (dissatisfaction) is that in life pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional. How much we suffer depends on us, our internal development, and our spiritual understanding and realization. Our pain and suffering point out to us where we are most attached to ourselvesour body, for example, or our loved ones; it shows us what we are holding on to the most. By recognizing this, we can learn to use loss and suffering in ways that help us to grow wiser and become more at peace with ourselves and the universe.

I believe that this is the time to become warriors for peace and dialogue, not warmongers or mere worriers. We must learn the hard lesson that without the pain of inner irritation, the pearls of wisdom will not be produced within us. I lovingly call this The Pearl Principle: no pain, no transformative gain.

Inside an oyster, it takes an irritantlike a grain of sand or a bit of shellto stimulate the oyster to produce the mucous juices that engulf and surround the irritant, eventually hardening into a precious pearl. It is the same for us, regardless of how much we wish it to be otherwise. Difficulties and suffering produce the aspiration for spiritual enlightenment, and it is this aspiration which is needed to motivate us along the path of awakening and liberation. There is no growth without growing painsand the labor pains of giving birth to a new world and a new way of being can be the most painful yet rewarding of all.

I find that the Buddhist virtue, or paramita (transcendental perfection), that is most essential, most helpful for dealing with pain, difficulty, and suffering, is patience. The fourth paramita, Shanti, advocates patience, forbearance, acceptance, tolerance, forgiveness, and allowing. It requires a certain kind of expansion, a generous embracing and merging, rather than retracting and separating. It takes a lot of time, patience, and fortitude, but I think Shanti helps me the most to bear pain and sorrow. It takes courage and stamina to hang in there, but it's worth it in the long run.

Face your difficulties realistically, rather than withdrawing from them, and riches can be yours. When faced with pain and misfortune, simply stop and center yourself in the present moment, here and now; take a deep breath, sit down and concentrate; pray. Or try to laugh, one way or another. Laugh the cosmic laugh, lighten up, and be en-lightened.

Lama Surya Das

Cambridge, Massachusetts

January 2003

CHAPTER ONE

Making Sense of

the Madness

Why does God allow guns? Why did Jonathan's daddy have to die? Why was Margaret born blind?

AMELIA,

four years old

W hy is there illness, death, and suffering? Why are we separated from those we love? Why is there pain? Why do bad things happen? Why do people hurt each other? Why is life so filled with loss? And the universal question: Why do bad things happen to me? Stuff happenseveryone knows thatbut why does it happen to me, why am I so often in the midst of it!

Next page