ALSO BY IAN JOHNSON

A Mosque in Munich: Nazis, the CIA, and the Rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in the West

Wild Grass: Three Stories of Change in Modern China

Copyright 2017 by Ian Johnson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Owing to limitations of space, permissions to reprint previously published material can be found following the bibliography.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Johnson, Ian, [date].

Title: The souls of China : the return of religion after Mao / Ian Johnson.

Description: First Edition. | New York: Pantheon Books, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036412 (print) | LCCN 2016044144 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101870051 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781101870068 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ChinaReligion20th century. ChinaReligion21st century.

Classification: LCC BL1803 .J645 2017 (print) | LCC BL1803 (ebook) | DDC 200.951/09051dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2016036412

Ebook ISBN9781101870068

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover images: (bottom left and middle) Sim Chi Yin /VII Photo / Redux; (upper left) courtesy of the author

Cover design by Janet Hansen

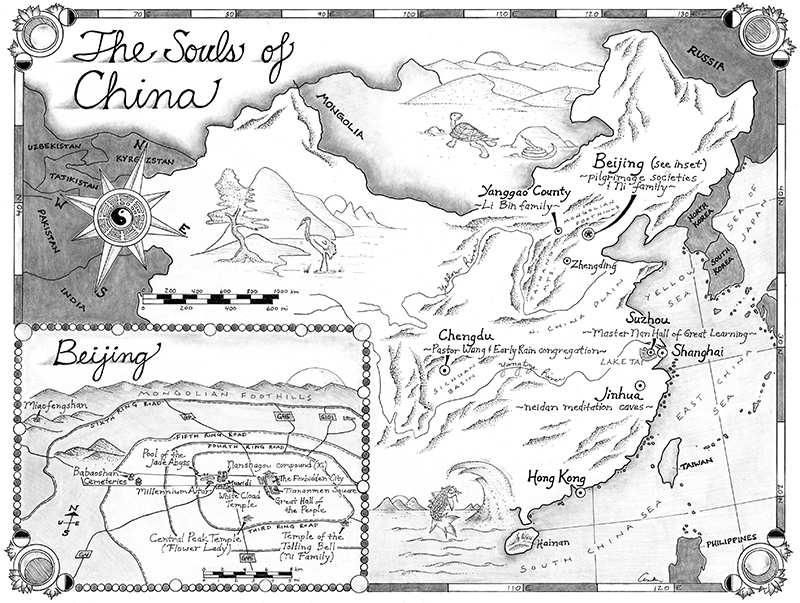

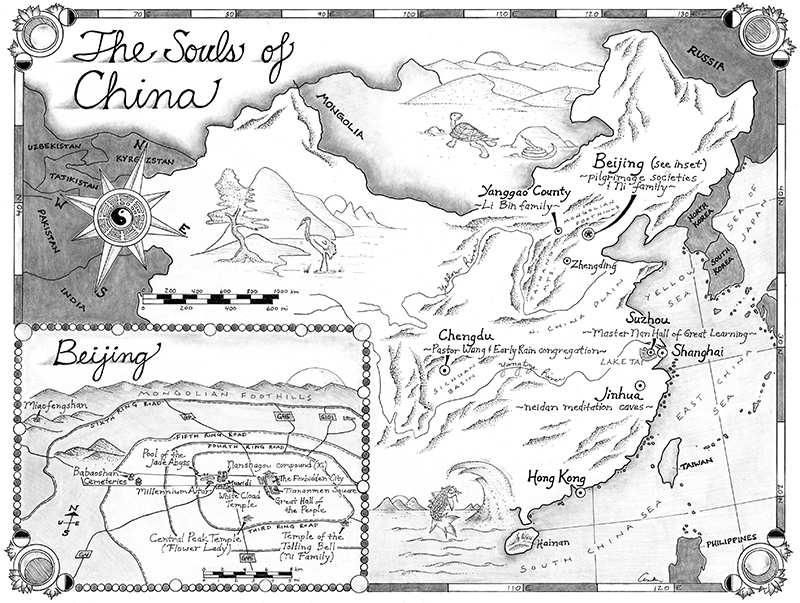

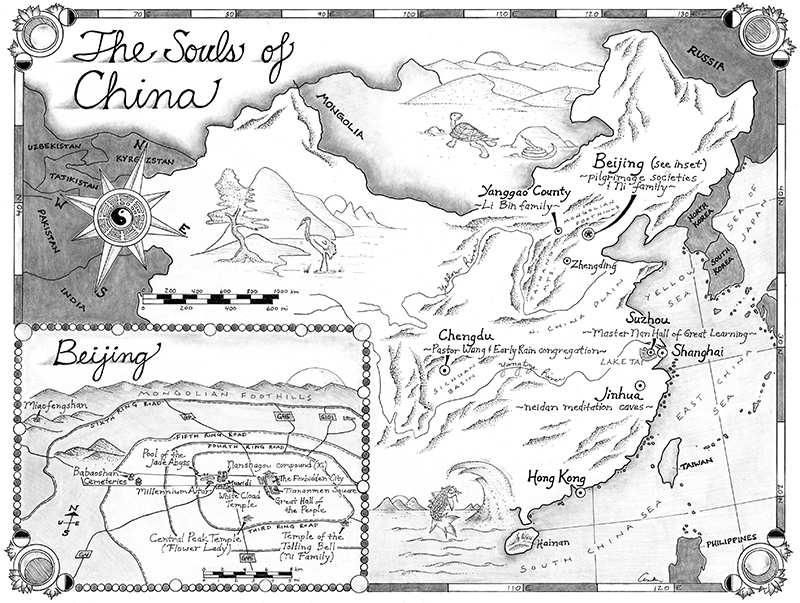

Map by Angela Hessler

v4.1

ep

Contents

Heaven sees as my people see. Heaven hears as my people hear.

BOOK OF DOCUMENTS

But now they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared for them a city.

HEBREWS 11:16

Cast of Characters

THE BEIJING PILGRIMS

Ni Zhenshan, or Old Mr. Ni: the family patriarch and head of a pilgrimage association that runs a shrine on Miaofengshan, Beijings holiest site.

Ni Jincheng: the older son who becomes a reclusive Buddhist.

Ni Jintang: the younger son who helps run the pilgrimage association.

Qi Huimin: the tough manager of the association and devout believer.

Wang Defeng: the Communist Party official who led the reconstruction of Miaofengshan and remains its influential manager.

Chen Deqing, or Old Mrs. Chen: founder of a shrine on Miaofengshan and patron saint of a summertime pilgrimage to the Temple of the Central Peak.

THE SHANXI DAOISTS

Li Bin: the ninth-generation Daoist yinyang man, or funeral master, fortune-teller, and geomancer. He moves into the city against his fathers wishes.

Li Manshan, or Old Mr. Li: the father of Li Bin, he stays in the familys ancestral village.

Li Qing: the Li familys late patriarch, who revived traditions after the Cultural Revolution.

THE CHENGDU CHRISTIANS

Wang Yi: the former human rights lawyer and pastor of Early Rain Reformed Church.

Jiang Rong: Wang Yis wife and early convert to Christianity.

Zhang Guoqing: Early Rains liaison to marginal groups in society.

Zha Changping: the cerebral pastor of the Spring of Life Reformed Church.

Peng Qiang: former entrepreneur and Communist Youth League member who runs the Grace and Blessings Reformed Church.

Ran Yunfei: Bandit Ran, a mercurial essayist and Chengdus best-known public thinker, who is drawn to Christianity.

THE MASTERS

Nan Huai-chin: Buddhist meditation guru and interpreter of Chinese classics, he lives in a hermitage on Lake Tai.

Wang Liping: charismatic practitioner of a Daoist meditation technique called neidan, or internal alchemy, who teaches courses in the caves of southern China.

Qin Ling: Wangs chief disciple in Beijing.

Xiao Weijia: Qins husband and scion of an important Communist Party family.

T he Moon Year begins with no moon. The sky is black but for the stars; the moon lies unlit on the other side of the earth, invisible to our eyes. The Chinese call this the Lunar New Year, but it is best known as the Spring Festival, the celebration of a new season. The name seems wrong: the holiday falls in the winter month of January or February. It is cold and dark; the days still short. In northern China, snows can blanket the land. In the south, chilly rains penetrate every room, every layer of clothing. We feel gripped by the hopelessness of winter and wonder how this calendar ever functioned: How did it order time in one of the worlds oldest continuous civilizations?

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Chinese patriots had similar questions. They worried that their country was so backward that it would be torn apart by foreign powers. One of these reformers chief targets was Chinas traditional culture, especially its systems of belief, which they thought were superstitious relics that dulled people to the potential of science and progress.

The old-style calendar was an easy target. Few practices are as important to a society as how it measures time. In traditional China, calendars were made by artisans who used wood-block printing on tissue-thin paper to create colorful pieces of art decorated by gods and saints. They listed key holidays and reminders when certain ceremonies had to be carried out. On Chinese New Years Eve, the old calendar was scraped off the wall and the new one pasted up.

The traditional calendar was based on the moons orbit around the earth. It started on the second new moon after the Winter Solstice, which meant the traditional year began in late January or early February. Each month was one orbit of the moon around the earth. To Chinas modernizers, all of this seemed ridiculously out of date. By 1929, the forces for change were so strong that the government formally discarded the lunar calendar and replaced it with the Western Gregorian calendarthe solar calendar, based on the earths orbit around the sun. Since then, the year in China begins on January 1 and has 365 days, just like elsewhere.

And yet, with time, you notice that the lunar calendar still underpins how many Chinese dress, eat, worship, and pray. Even Chinese New Years other name, the Spring Festival, begins to make sense. In the West, spring starts on the Vernal Equinoxthe date in mid-March when day and night are about equally long. But in China, events are anticipated earlier; here, the buildup is the key. Late January or early February might seem too early to welcome spring, but in fact the days are warming. In January, Beijingers will tell you that if you want to skate on one of the citys lakes, you had better go now: after the start of the Moon Year, the ice will melt.