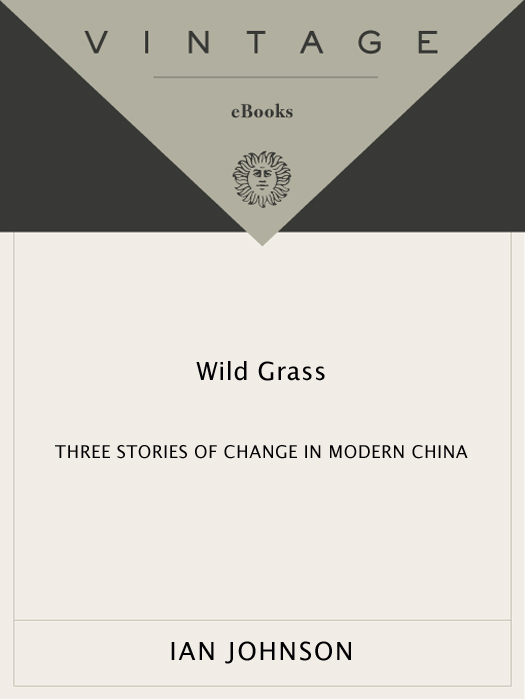

Acclaim for Ian Johnsons

wild grass

A gripping tale of a very few ordinary people and their extraordinary courage in fighting for their rights against the Communist Party leviathan.

The Washington Post Book World

Elegantly written. Poignant. Insightful, well-crafted. Likely to find a broad readership.

Boston Review

Cause for hope for Chinas future. In vivid detail, [Johnson] recounts cases that show that individual Chinese at last have hope that the legal system can help.

Foreign Affairs

Gripping taut, perceptive writing. Reads in parts like a John Grisham legal thriller.

Houston Chronicle

Johnson is a wonderful storyteller. His book is filled with evocative passages. He captures the resilient spirit of many Chinese people.

The Christian Science Monitor

Johnson writes well, wielding a remarkably gentle pen against the grossest injustices or when describing the most remarkable instances of personal bravery. The people written about here could wish for no better chronicler.

The Asian Review of Books

This years best general book on China.

China Economic Quarterly

IAN JOHNSON

wild grass

Ian Johnson is the Berlin bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal. In 2001, when he was the Journals Beijing correspondent, he won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Falun Gong. He lives in Berlin.

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, MARCH 2005

Copyright 2004 by Ian Johnson

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2004.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Some of the material previously appeared in slightly different form in The Wall Street Journal.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows:

Johnson, Ian, [date]

Wild grass : three stories of change in modern China / Ian Johnson.

p. cm.

1. Political activistsChina. 2. Government, Resistance toChina. 3. DissentersChina. 4. Civil rightsChina. 5. ChinaPolitics and government1976. I. Title.

JQ1516.J642004

323.040951dc22

2003058082

eISBN: 978-0-307-43025-0

Author photograph Otto Pohl

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

T O J EAN AND D ENIS

Wild grass strikes no deep roots,

has no beautiful flowers and leaves,

yet it imbibes dew,

water and blood and the flesh of the dead,

although all try to rob it of life.

LU XUN , Wild Grass, 1926

Contents

Prologue:

One Hundred Battles a Day

Prologue:

One Hundred

Battles a Day

Chinas rulers have developed a bad case of the nerves. Unemployment is high, corruption permeates daily life and relations with the outside world result in recurring crises. Often these tensions erupt in small protests, sometimes against the government, other times against outsiders. They usually end after a few days, often crushed, sometimes petering out when a few ringleaders are arrested and the protesters demands partly met. But they are never resolved, surfacing like a corpse that wont stay under.

When the anniversaries of these protests come around a year later, commemorations are held and petitions delivered. Some of these grudge dates are intensely local: a familys memory of its house torn down to make way for a corrupt real estate project, or a village that commemorates a local leader arrested for standing up to abuse. Other commemorations are shared by millions: the killing of students or the banning of a popular religion.

The government, ever watchful for challenges to its rule, tries to keep track of them all. Protests, arrests, detentions: each year the victims try to commemorate these disasters, and each year the government tightens up around these dates. Slowly, the countrys mental calendar has become a series of overlapping scabs and sores.

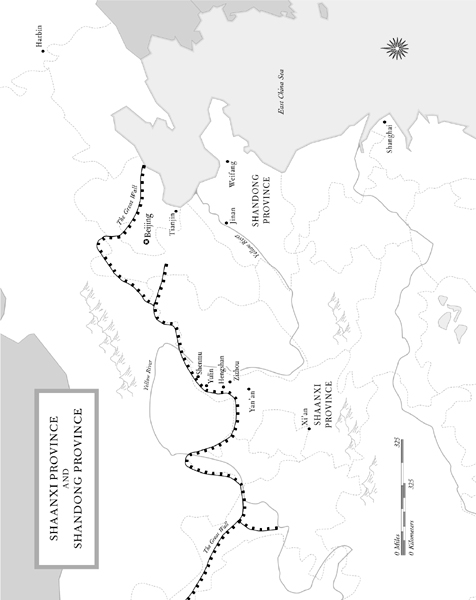

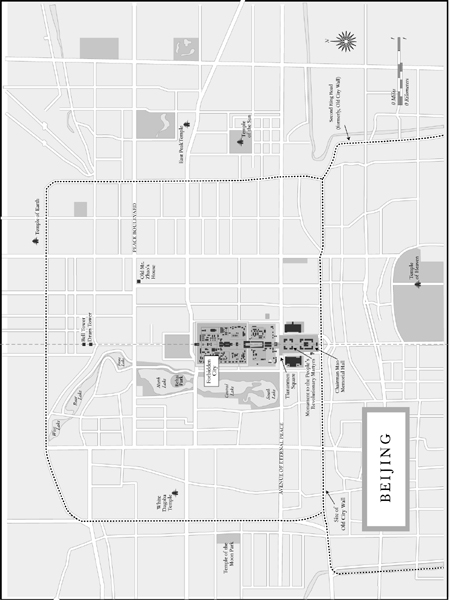

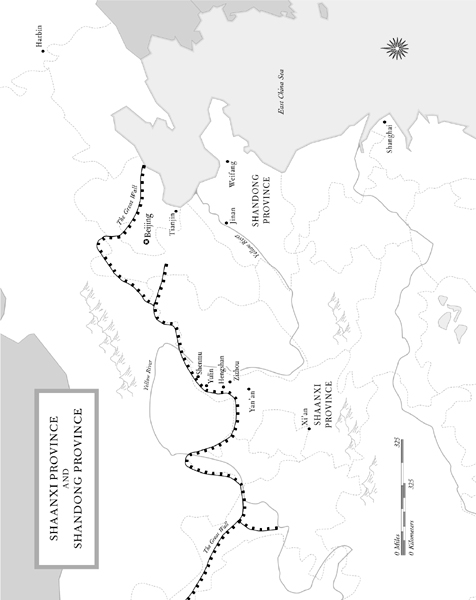

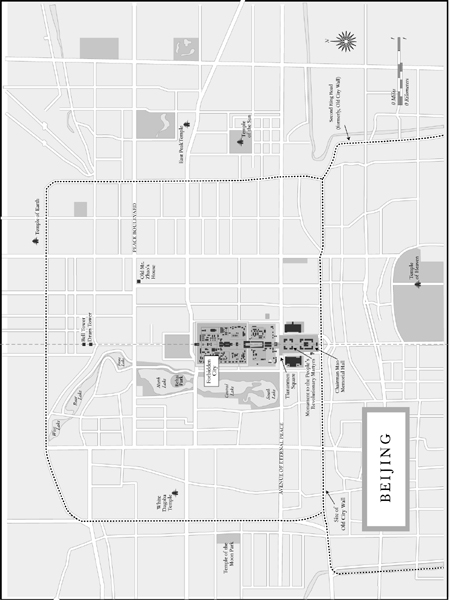

Beijing, the countrys political and spiritual capital, where most protests take place, is especially affected because petitioners from around the vast republic ultimately make their way there. Each sensitive date is accompanied by increased police patrols, roundups of dissidents and tapped phones. The signs are not always obvious, but once they are known, they are unmistakable: the triple-teamed soldiers that cordon off diplomatic compounds, late-night police roadblocks, roving patrols on trains heading for Beijing, the sealing off of the cavernous Tiananmen Square, accessible only to those who present their identity cards for inspection.

Chinas government wasnt always so unsure of itself. Shortly after taking power in 1949, the Communist Party enjoyed some popular success. It united China for the first time in a century, put people to work and redistributed land. Even when the disasters cameand they came fastthe party didnt have to worry too much about unrest. Famines and persecution were regular occurrences during the partys first three decades in power. But China was frozen by totalitarian rule. Even small protests to mark these misdeeds were difficult.

Then, the totalitarian dictatorship of Chairman Mao Zedong collapsed with his death in 1976. Weakened by thirty years of failed policies, the party tried to win back popular support by withdrawing its control over peoples personal lives and by allowing capitalist-style economic reforms. Over the past decades this looser form of control has succeeded in raising living standards but hasnt helped the party win deep-rooted legitimacy.

With the government no longer micromanaging their daily lives, people now have time to travel, to reflect and, slowly, to demand more. With prosperity and better education, Chinese people have begun forming independent centers of power outside government controltrade unions, religious organizations and clubs. It was the development of this civil society that helped bring about the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe late last century. Now, these groups are eroding the power of Chinas Communist Party.

It would be unfair to say that this cacophony of demands has paralyzed Chinas leaders. On key economic issues, which they view as vital to their survival, the mandarins can push through reforms. Hence, Chinas admission into the World Trade Organization, a sign that whatever its name, the Peoples Republic of China practices little in the way of communist economics. China now has stock markets, labor markets and a more open economic system than some developed countries.