Table of Contents

Ghalib

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

Editorial Board

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

Burton Watson

Wei Shang

GHALIB

Selected Poems and Letters

Edited and translated by

Frances W. Pritchett and Owen T. A. Cornwall

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Pushkin Fund in the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Frances W. Pritchett and Owen T. A. Cornwall

All rights reserved

EISBN 978-0-231-54400-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ghalib, Mirza Asadullah Khan, 1797-1869, author. | Pritchett, Frances W., 1947- editor, translator. | Cornwall, Owen T. A., editor, translator. | Ghalib, Mirza Asadullah Khan, 1797-1869. Works. Selections. | Ghalib, Mirza Asadullah Khan, 1797-1869. Works. Selections. English.

Title: Ghalib : selections from his Urdu poetry and prose / edited and translated by Frances W. Pritchett and Owen T.A. Cornwall.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2017. | Series: Translations from the Asian classics | English translation and Urdu text. | Includes bibliographical references, appendices, glossary, and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028955 (print) | LCCN 2016048551 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231182065 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231182065 (electronic)

Classification: LCC PK2198.G4 A2 2017 (print) | LCC PK2198.G4 (ebook) | DDC 891.4/3913dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028955

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Contents

Ghalib loved and cherished his friends, and we want to offer a toast to ours. We owe to Shamsur Rahman Faruqi a larger debt than we can describe. We thank Aftab Ahmad, Allison Busch, Arthur Dudney, Satyanarayana Hegde, Pasha M. Khan, C. M. Naim, Sean Pue, Dalpat Rajpurohit, and Zahra Sabri for their advice, help, and moral support; we also offer a libation to the memory of Aditya Behl. We thank Sheldon Pollock for encouraging us to undertake this project. Finally, Jennifer Crewe and the staff of Columbia University Press have been a pleasure to work with, and we are greatly in their debt.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Mughal empire, once in control of almost the entire Indian subcontinent, was hanging by a thread. The repeated invasions by Iranians, Afghans, and Marathas in the course of the eighteenth century had left the Mughal emperors in possession of little beyond the imperial Red Fort in Delhi and their title. In 1803, the British East India Company officers with their Indian sepoy army captured Delhi and consolidated their hold on North India. From then on, the Mughal emperors were British pensioners.

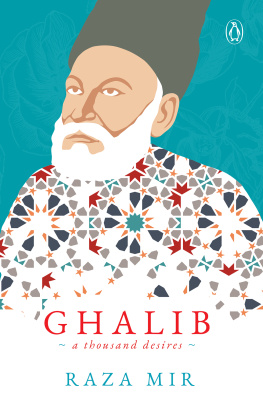

The traditional date of Ghalibs birth is 1797, in Agra, into a family of Turkish descent and military background. Ghalibs father died when the boy was only five, and the family was supported by an uncle, Nasrullah Beg Khan. This uncle, having surrendered the Agra fort to the British in 1803, joined the East India Company army. When he died in 1806, Ghalib was entitled to a significant portion of his British pension, but another, better-connected relative diverted much of it. For decades Ghalib petitioned the indifferent British bureaucracy for his rightful share, even making an arduous but ultimately vain journey to the East India Companys capital in Calcutta in 1828. His financial circumstances were always precarious, but he nevertheless aspired to live in a style befitting a late-Mughal aristocrat.

The young Ghalib was precocious, talented, and hardworking. In 1813 he moved permanently from Agra to Delhi. At nineteen he compiled his first collection of poetry, and during his twenties he continued to compose ghazals in the highly Persianized Urdu that had begun to supplant Persian itself in the literary life of Delhi. His middle decades were devoted chiefly to poems and letters in Persian.

Persian was the great tradition on which he wanted to leave his mark. Although he felt little or no nostalgia for the political achievements of the Mughal empire, he cultivated the aesthetics of the sixteenth-century Persian poets who had migrated between the Safavid and Mughal empires in pursuit of patronage. In this respect, he might properly be considered the last great writer of the classical Indo-Persian poetic tradition, before the devastating social and cultural ruptures of 1857, when a rebellion against the British was met with ferocious reprisals. But to Ghalibs regret, Persian was increasingly on the wane in North India during his lifetime.

Late in life he composed additional ghazals in Urdu, at the behest of Bahadur Shah Zafar (r. 18371858), the last Mughal emperor, and other patrons. But he always insisted that he was really a Persian poet, for whom Urdu was only a secondary poetic language. Some evidence of his pride in his Urdu poetry can be found in his letters (and in the closing-verse of ghazal 19, though it is early), but only enough for a kind of minority report. Ironically, it was his Urdu poetry and letters that brought him fame, while his work in Persian has received very little attention.

As part of his aristocratic self-image, Ghalib took pride in his position of honor at the East India Companys durbar, where as a member of a prominent family he was accorded an elaborate title and a ceremonial robe of honor. His pension, even when supplemented by stipends from rich admirers of his poetry, was barely enough to support his household. He had been married at the age of thirteen to Umrao Begam, a distant relative from a richer branch of the family; they had a number of children, all of whom died in infancy or early childhood. The couple adopted two orphaned boys from his wifes side of the family and raised them affectionately. Relations between Ghalib and his wife were always correct, in the formal style of the time, but the two seem not to have been particularly compatible in temperament. His biographer and one-time pupil Altaf Husain Hali reports that Ghalib was a dutiful husband: he lived in the mens quarters, but his wife duly looked after his food and other needs, and he never failed to go once a day to the womens quarters at an appointed time to see her; he was very kind to her relatives as well.