Shi i Islam

A Beginners Guide

Shii Islam

A Beginners Guide

Moojan Momen

A Oneworld Paperback Original

Published by Oneworld Publications 2016

This ebook edition published in 2016

Copyright Moojan Momen 2016

The right of Moojan Momen to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781780747873

eISBN 9781780747880

Typeset by Jayvee, Trivandrum, India

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London, WC1B 3SR

England

Contents

Prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, few people in the West were conscious that a separate sect of Islam called Shii Islam existed and even those who were aware of this were not very clear who the Shiis were, where they lived, what they believed or what made them different to the majority Sunni community. Even in academic circles, there were very few who had studied Shii Islam and there was little literature that dealt with the central concerns of this group. Given this level of ignorance, it is perhaps not surprising that the Islamic Revolution left many bewildered. Where had this revolutionary fervour come from? Why had almost no one been able to predict it? What was the best way of dealing with the new power in the Middle East?

It was not only the West that the Iranian Revolution caught by surprise. Many Muslims were just as mystified by what had occurred. For centuries, Sunni Muslims had been used to discounting the Shiis, considering them an irrelevance to the politics and economics of the Middle East. In only one country, Iran, did Shii Islam seem to be of any importance and even there, the religion appeared to be taking a back seat to political concerns.

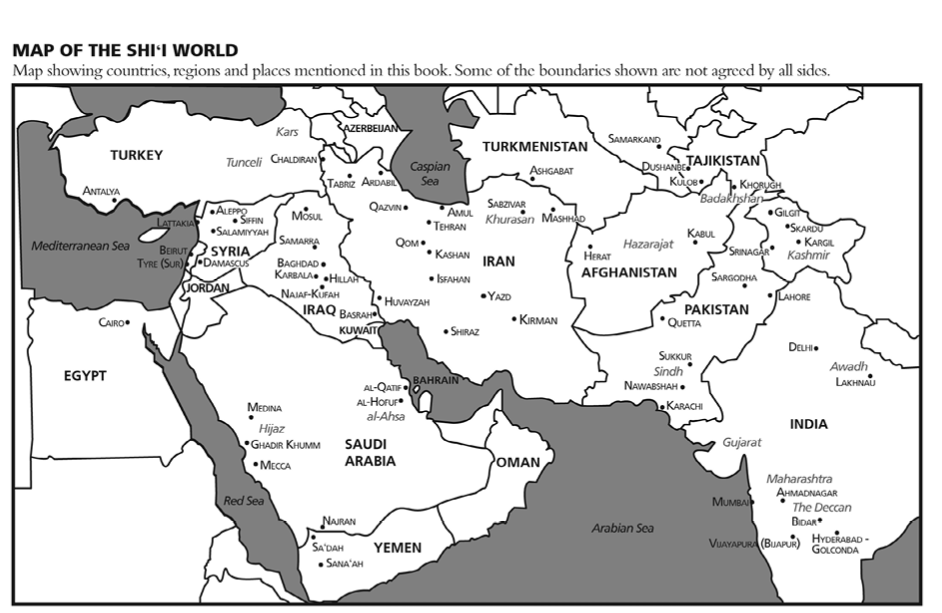

The Revolution was enough to put Shi i Islam on the map but further upheavals arose from the newly-discovered phenomenon of Shi i Islam. Suddenly people discovered that the destabilization of Lebanon was being caused by a militant Shi i group; unrest in Iraq against Saddam Hussein was due to a Shi i movement; turmoil in Syria was found to be due to Sunni opposition to a minority Shi i government; political unrest in the oil-rich province of Saudi Arabia was also noticed to be coming from Shi is; and civil strife and violence in Pakistan and India were now being described as due to Sunni-Shi i animosity. All this unrest had existed before 1979 but had been attributed to political and economic factors. Now everyone was seeing a religious dimension to these conflicts.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, a slew of experts promptly appeared and opinions were given about how Shi i Islam was inherently revolutionary and destabilizing and how oppressed Shi i masses were now demanding a voice and power in proportion to their numbers. These explanations were not incorrect but were often superficial and failed to provide an understanding of what was actually going on and the variations in Shi i Islam among countries, regions and groups. To make matters worse, political decisions were then based on these explanations, leading to errors by Western statesmen and a widening of the gulf of misunderstanding between the West and the Shi i world.

Relations between Shii Islam and the West since 1979 have been marked by a continuing series of surprise moves on the Shii side and paralysis and errors of judgement by the West. Every time people think the situation in Iran and in the Shii world is starting to settle and become more understandable, and therefore more predictable in terms of the sort of theories and mechanisms by which the West usually explains social and political affairs, the Iranian government or some other Shii group comes up with a surprise that requires fresh explanations and new models. The 1979 Iranian Revolution left many governments floundering in ignorance, not knowing how to approach the new government in Iran; but just as people were getting used to the idea of the Islamic Revolution and contemplating negotiating with the new government, in a break with the norms of international affairs, students seized the American embassy in Tehran and took 65 Americans hostage. A year later, the Iran-Iraq war began and again the West was badly informed and took the side of Saddam Hussein in the conflict, despite evidence of his war crimes (his use of chemical weapons). When Americas intervention in the Lebanese Civil War culminated in the first major episode of suicide bombing against the United States (when the Beirut embassy and the American barracks were bombed in 1983), the attacks took everyone in the West by surprise and induced such a state of panic that within four months all American troops had been withdrawn from Lebanon. The unexpected twists have continued with the strong Green Movement that rose in protest against the 2009 election victory of President Ahmadinejad and the rise of the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Iran is, in fact, a country full of paradoxes and these extend to other Shii communities as well. For example, people think they know that women are oppressed by the Islamic regime in Iran and while that is true, women in Iran have the vote, have levels of literacy comparable with women in the Western world, and make up 65% of university students (70% of science and engineering students) and 40% of the countrys salaried workers.

There is thus a great deal of room for improvement in the Wests knowledge of Shii Islam and this improvement is vital if Western policy decisions and initiatives in the area are to be more coherent and constructive. Although this book cannot claim to remedy this situation completely, it is hoped that it will at least shed some light on the complexities of Shii Islam and its role in the world.

This book is intended to be a brief introduction to the Shi i branch of Islam for the general reader. In a short book such as this, it is not possible to give a detailed account of all the Shi i sects and sub-groups. I have, therefore concentrated on the main grouping of Shi is, the Usuli School of the Ithna- Ashari (Twelver) sect of Shi i Islam, which represents some 80% of the worlds Shi is. When reference is made to Shi is or to Twelvers in this book, therefore, it is this group that is intended unless specifically designated otherwise. The early history of the other Shi i groupings is included in Chapter 2 and a brief account given in Chapter 8. Also, when writing about doctrines and practices, I have concentrated on those areas where Shi i Islam differs most from Sunnism, rather than attempting a comprehensive coverage.

In writing this book, there has been some question over what terminology to use. One problem has how to describe the main grouping of Shiis in the world today. Some authors have called this group the Imamiyyah, but that is only used of them in the early histories and can be regarded as also being an accurate designation of another grouping of the Shiis, the Ismailis. They are also sometimes, and in some areas, called Jafari Shiis and Matawilah. Most call themselves the Ithna-Ashariyyah to signify that they hold to a succession of Twelve Imams and so in this book I have followed this designation and translated this directly as the Twelvers. The next problem relates to the adjective to use in relation to Shiism. In Arabic, the word Shiah is a collective noun and should be used only for a group of the followers of the religion. However, in Persian, Shiah is pronounced Shieh and is frequently also used as an adjective (and therefore also as a noun for a person of this group). This usage is also common among Shiis of the Indian subcontinent because of the historic predominance of Persianate culture there. Since this usage is foreign to Arab Shiis, however, I have used the word Shii as the adjective from Shiism and only use Shiah as a collective noun.