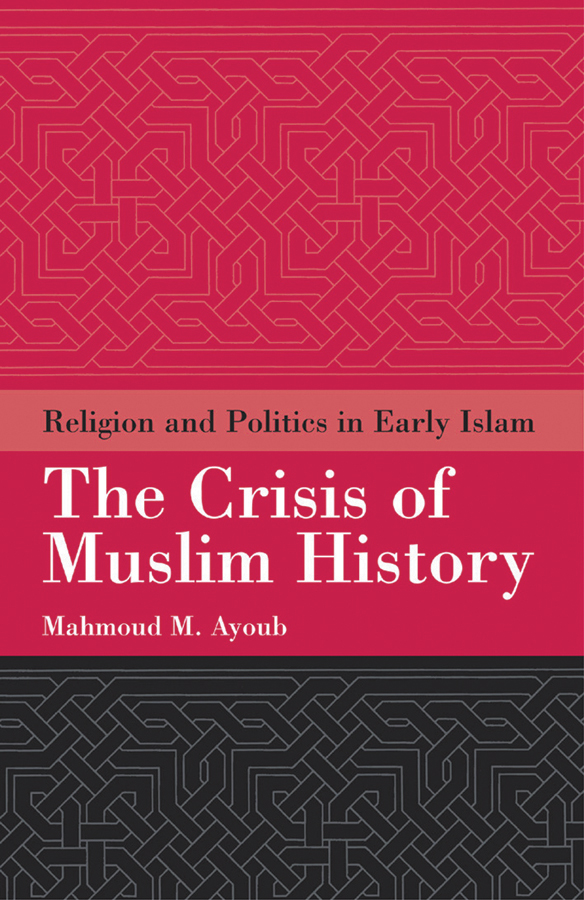

The Crisis of

Muslim History

Religion and Politics in Early Islam

The Crisis of

Muslim History

Religion and Politics in Early Islam

Mahmoud M. Ayoub

A Oneworld Book

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

First published by Oneworld Publications, 2003

Copyright Mahmoud M. Ayoub 2003

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781851683963

ISBN 9781780746746 (ebook)

Cover design by Saxon Graphics, Derby UK

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London

WC1B 3SR

England

www.oneworld-publications.com

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Contents

Appendix I The Four Rightly Guided Caliphs in their

Own Words

Preface

This monograph is the result of a larger research work, which is yet to be completed, dealing with the life and time of the Imm Jafar al-diq. The aim of both works is to study the interaction of religion with politics in early Islam. The present study, however, is limited to the period of the first four caliphs, which is believed by the majority of Muslims to represent the Divinely Guided caliphate.

The period of Prophetic rule in Madnah belongs to sacred history. This is because, in the view of Muslims, it was guided not by human wisdom but Divine revelation, and hence can never be duplicated. Thus Muslim history, properly speaking, begins not with the career of the Prophet, nor even with his migration (hijrah), but with his death. It begins with the communitys faltering steps towards building a concrete abode (dr) for Islam, whose foundations were laid by the Prophet and his intimate Companions. It begins with the rule of the four Rightly Guided caliphs, with which this study is concerned.

An adequate understanding of this formative period is crucial for our understanding of subsequent Islamic thought and history, yet it has been the subject of only a few specialized studies which are not readily accessible to the student of religion. The aim of this work therefore, is to fill this gap, not only for students of religion in general, but also for students of Islam. This small volume is intended to supplement the information usually presented in general introductions to Islam used by both graduate and undergraduate students in colleges and universities where English is the medium of instruction. A list of further readings in English translations of primary sources, when available, are referenced with the originals in the bibliography appended to this monograph.

This work was begun several years before the appearance of Professor Madelungs seminal book, The Succession to Muammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate,on the same subject. It is different in both scope and purpose. For, while Madelungs work ends with the consolidation of Umayyad power under the able Marwanid Caliph Abd al-Malik b. Marwn (r. A.H. 6586/684705 C.E.), the present volume will conclude with the death of Al, the end of whose rule was coterminous with the period of the normative or Rightly Guided caliphate.

It remains for me to acknowledge with gratitude some of the organizations and people who helped in one way or another in the making of this study. My first indebtedness is to the Muhammadi Islamic Trust of Great Britain and its late director Commander Qasim Husayn who started me on this research venture. I am also indebted to the Iranian United Nations Mission, and particularly his Excellency, former Ambassador and present Foreign Minister Dr. Kamal Kharrazi for a generous grant which enabled me to complete the research for the book on the Imm al-diq, on which this study is based. I am also grateful to Ms. Rose Ftaya for her patient and thorough editing of the book.

I undertook this work fully aware of the sensitivity of its subject and my own inadequacy for such a task. I have done my best to let the sources themselves tell the story of this crisis of Muslim history. This meant that little attention is paid to Western scholarship, not because I am not cognizant of the great contributions Western scholars have made to a better understanding of Islam and its civilization, but because I wish to let classical Muslim historians and traditionists give their own account of their own formative history. My intention is not to offend, defend, or apologize for anyone, any idea, legal school, or doctrine. My only hope is that this book will fulfill its stated purpose, which is to provide a useful introduction to the study of a crucial period of the history of Islam and its people.

Mahmoud M. Ayoub

Department of Religion

Temple University

Philadelphia

Rab al-Awwal, 1424 / May, 2003

Introduction

No, by God, be of good cheer, for God would never disgrace you! You surely treat your next-of-kin with kindness. You always speak the truth and endure weariness patiently. You receive the guest hospitably and lend assistance in times of adversity.

Islam came into a society governed by moral principles based, not on faith in a sovereign God to whom all beings must answer on a day of judgment, but on time-honored customs which embodied certain values capable of holding society together and preserving its moral fabric. The words quoted above with which Khadjah, the Prophets wife, sought to reassure him in his moment of deep spiritual and psychological crisis do not invoke religious piety or right belief, but moral values of kindness, patience, hospitality, and reliability. Islam affirmed these values, gave them a broader moral framework of social responsibility, and deepened their religious meaning. It enjoined kindness not only to ones next-of-kin but to the orphan, the needy, and the wayfarer. It called for patience and steadfastness not only in times of misfortune, but also in resisting oppression and wrongdoing whenever it might be found. Through obligatory alms (zakt) Islam made social responsibility a religious duty and an act of worship and purification.

Muammad ruled the first Muslim commonwealth which he founded in 622, twelve years after his prophetic call primarily as a prophet. His role as a statesman was only a means of realizing a sociopolitical order based on a revealed law (sharah). To this end, he struggled for a base of operation until he secured a safehaven in Madnah. From that secure base the Prophet, his fellow Immigrants (muhjirn), and Supporters (anr) waged a continuous battle against his own recalcitrant people for the spread of the new faith with its community and power. That being the ultimate objective, all hostilities were forgotten as soon as the goal was achieved. The Prophets aim was to establish a faith-community rather than an empire. He died, therefore, without leaving a clear and concrete political model or apparatus that could sustain the vast empire which arose with amazing rapidity following his death.

The two primary frameworks within which the Islamic social order was constructed were the life-example (sunnah