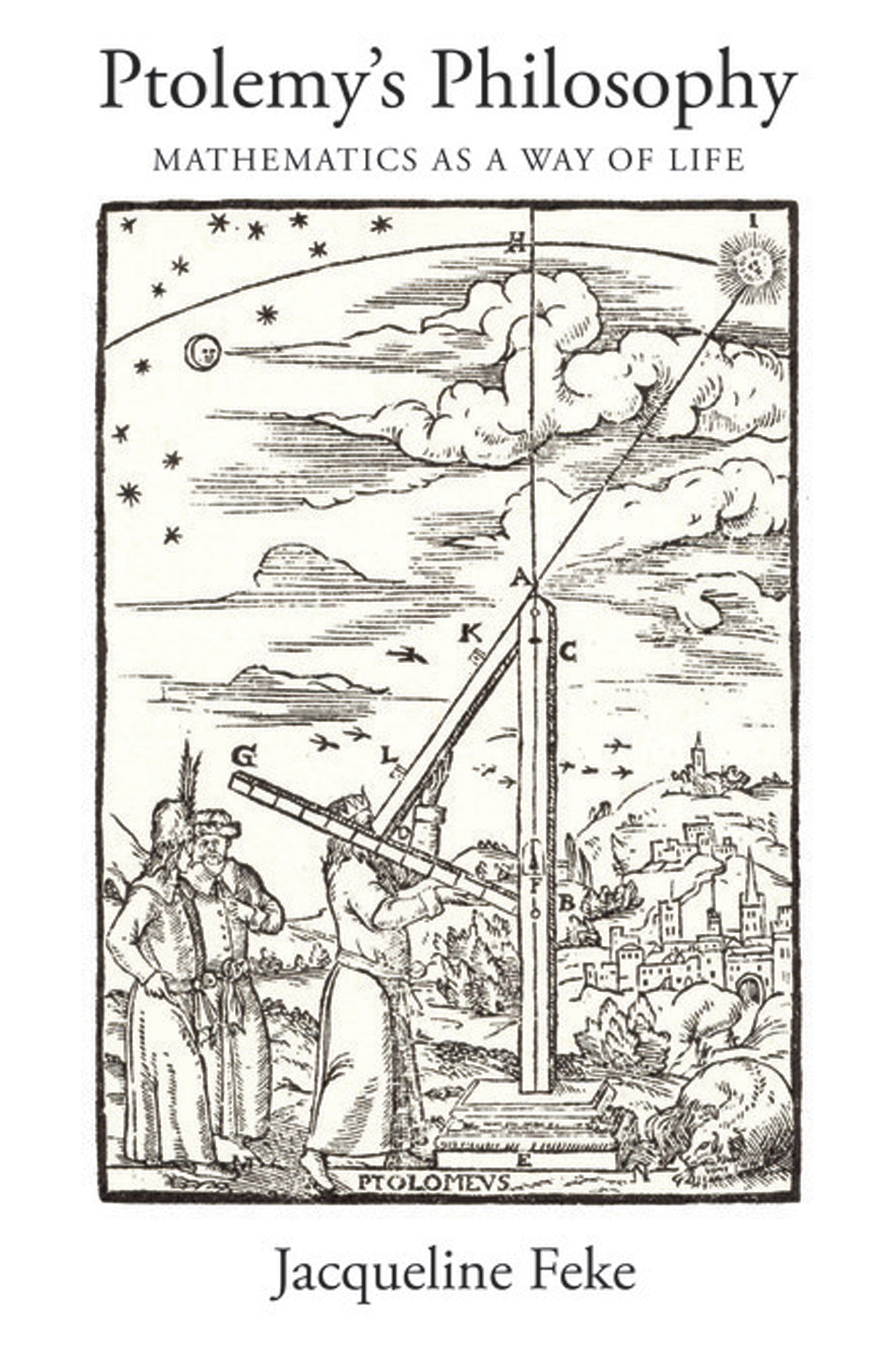

PTOLEMYS PHILOSOPHY

Ptolemys Philosophy

MATHEMATICS AS A WAY OF LIFE

JACQUELINE FEKE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017962530

ISBN 978-0-691-17958-2

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Al Bertrand and Kristin Zodrow

Production Editorial: Jenny Wolkowicki

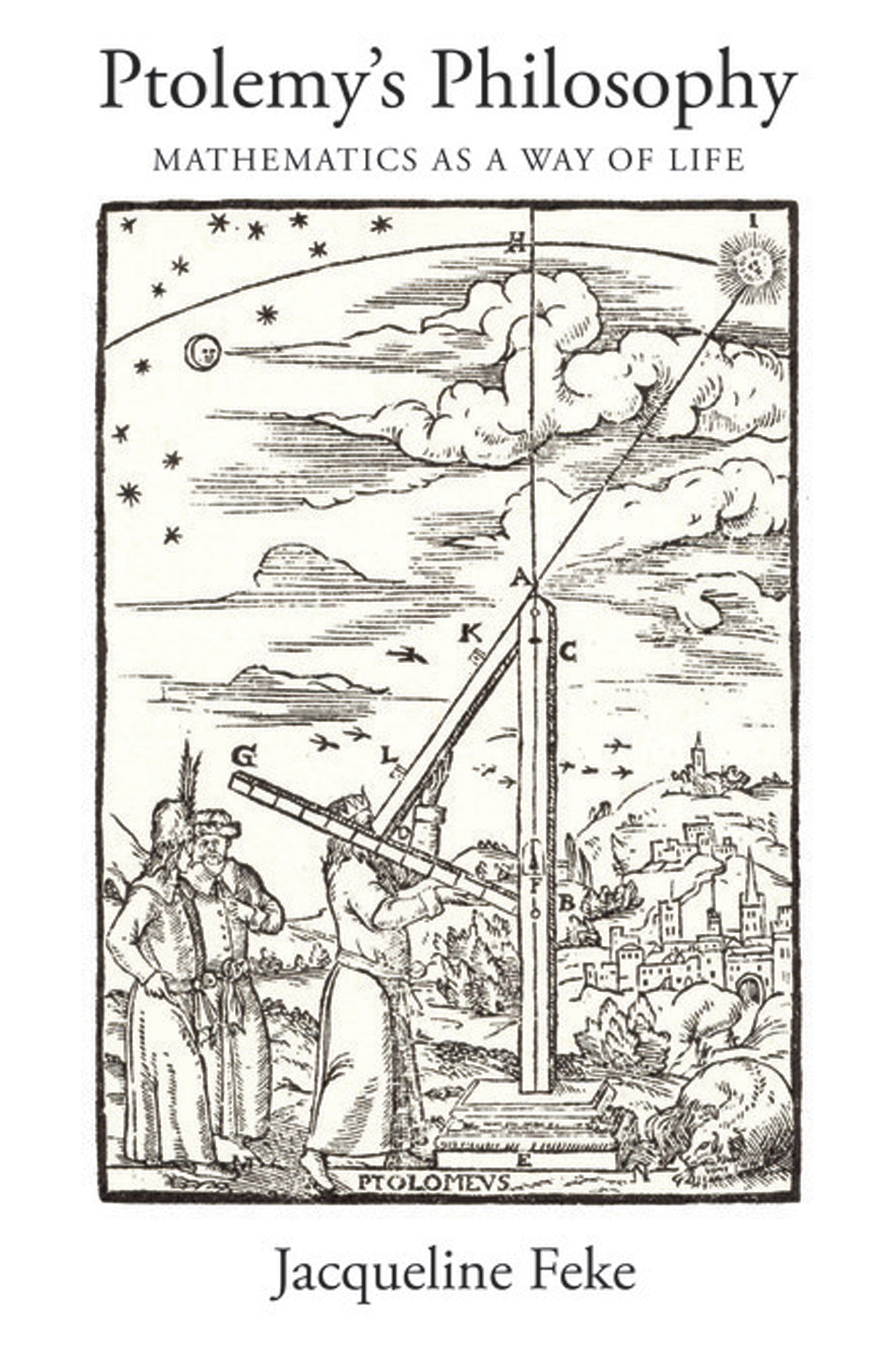

Jacket image: Ptolemys triquetrum (or parallactic instrument) according to William Cunninghams The Cosmographical Glasse, conteinying the Pleasant Principles of Cosmographie, Geographie, Hydrographie, or Navigation (London: John Day, 1559)

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford

Copyeditor: Maia Vaswani

This book has been composed in Arno Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Carol and Gilbert T. Feke

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN 2002 as an undergraduate student at Brown University, I was encouraged by Debby Boedeker, my then honors thesis supervisor, to meet David Pingree. I asked him where I could go to get a PhD studying the history of ancient science, and he gave me a simple answer. He told me that there was only one place to go in North America and that was the University of Toronto to study under Brown alumnus Alexander Jones. To this day, I dont know if Pingree was exaggerating or if he really believed that Uof T was the only place to be, but I followed his wise counsel. Alex Jones taught me how to be a historian. Brad Inwood guided my research in ancient philosophy and encouraged me to make my mark by focusing my research on Ptolemy. Craig Fraser mentored my research in the history of mathematics more broadly. The result, so many years later, is this book.

I am grateful to more people than I can mention for their instruction, mentorship, and friendship. In addition to Debby, David, Alex, Brad, and Craig, without whom this book would not be possible, I would like to thank Vincenzo De Risi for funding my research at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; Orna Harari for her professional and scholarly support; Stephan Heilen for giving feedback, especially on my analysis of Ptolemys astrology; Alain Bernard for motivating me to ask new questions about Ptolemys philosophy; Nathan Sidoli for showing me that success as an emerging scholar of ancient mathematics is possible; Vicky Albritton, Fredrik Albritton Jonsson, Daryn Lehoux, Patricia Marino, and Paul Thagard for coaching me through the early stages of book publishing; and all of the colleagues and friends from whom Ive learned and on whom Ive leaned from the University of Toronto, Stanford University, the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, the University of Chicago, and now the University of Waterloo. I am grateful to the many scholars who have asked questions and made comments on my work at numerous conferences and colloquia over the years, and I also would like to thank the anonymous referees for their suggestions. Above all, Id like to thank my parents, Carol and Gilbert T. Feke. It is to them that I dedicate this book.

PTOLEMYS PHILOSOPHY

Introduction

CLAUDIUS PTOLEMY is one of the most significant figures in the history of science. Living in or around Alexandria in the second century CE, he is remembered most of all for his contributions in astronomy. His Almagest, a thirteen-book astronomical treatise, was authoritative until natural philosophers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries repudiated the geocentric hypothesis and appropriated Nicolaus Copernicuss heliostatic system of De revolutionibus. Ptolemy also composed texts on harmonics, geography, optics, and astrology that influenced the study of these sciences through the Renaissance.

Ptolemys contributions in philosophy, on the other hand, have been all but forgotten. His philosophical claims lie scattered across his corpus and intermixed with technical studies in the exact sciences. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries development of discrete academic disciplines let the study of Ptolemys philosophy fall through the cracks. When scholars do make reference to it, they tend to portray Ptolemy as either a practical scientistmostly unconcerned with philosophical matters, as if he were a forerunner to the modern-day scientistor a scholastic thinker who simply adopted This monograph is the first ever reconstruction and intellectual history of Ptolemys general philosophical system.

Concerning Ptolemys life we know nothing beyond approximately when and where he lived. In the Almagest, he includes thirty-six astronomical observations that he reports he made in Alexandria from 127 to 141 CE. Another unaccredited observation from 125 CE may be his as well. Therefore, Ptolemy completed the Almagest sometime after 146/147 CE. In addition, Ptolemy makes reference to the Almagest in several of his later texts. The life span that this chronology requires is consistent with a scholion attached to the Tetrabiblos, Ptolemys astrological text, indicating that he flourished during Hadrians reign and lived until the reign of Marcus Aurelius, who became Roman emperor in 161 CE but ruled jointly with Lucius Verus until 169 CE. Thus, we can estimate that Ptolemy lived from approximately 100 to 170 CE.

Concerning any philosophical allegiance, Ptolemy says nothing. In his texts, he does not align himself with a philosophical school. He does not state who his teacher was. He does not indicate in what his education consisted or even what philosophical books he read. In order to discern where his philosophical ideas came from, one must mine his corpus, extract the philosophical content, and, with philological attention, relate his ideas to concepts presented in texts that are contemporary with his own or that were authoritative in the second century. Unfortunately, what survives of the ancient Greek corpus is but a fraction of what was written and we have very little from Ptolemys time. It is impossible to determine what exactly he read or even where he read it, as it is dubious that the great Alexandrian library was still in existence. At best we can place Ptolemys thought in relation to prevailing ancient philosophical traditions.

The first century BCE to the second century CE is distinguished by the eclectic practice of philosophy. The Greek verb eklegein means to pick or choose, and the philosophers of this period selected and combined concepts that traditionally were the intellectual property of distinct schools of thought. Mostly, these philosophers blended the Platonic and Aristotelian traditions, but they also appropriated ideas from the Stoics and Epicureans. The label eclecticism has long held a pejorative connotation in philosophy, as if eclectic philosophers were not sufficiently innovative to contribute their own ideas, and the philosophy of the periods before and after this seemingly intermediate chapter in ancient philosophy were comparatively inventive, with the development of the Hellenistic movements, including the Stoic, Epicurean, and Skeptic, and the rise of Neoplatonism, respectively. Nevertheless, John Dillon and A. A. Long revitalized the study of eclectic philosophy. So-called middle Platonism and the early Aristotelian commentary tradition have received more attention in recent years, and their study has demonstrated that the manners in which these philosophers integrated authoritative ideas are themselves noteworthy.

Next page