Copyright 2000 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-09259-1

eISBN 978-0-691-21411-5

www.pup.princeton.edu

Preface

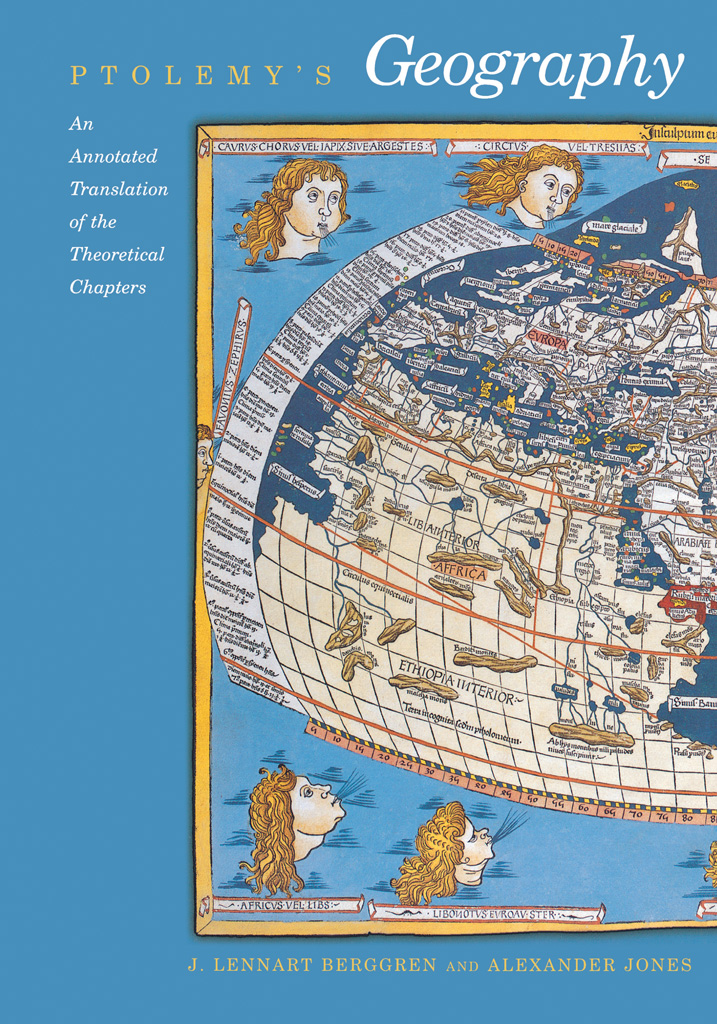

On any list of ancient scientific works, Ptolemys Geography will occupy a distinguished place, and Ptolemys contributions to ancient, medieval, and Renaissance geography receive respectful notice in books devoted to the history of science.

It is, however, the respect usually reserved for the dead, and one who wishes to examine the sources firsthand will soon come to an impasse. No complete edition of the Greek text has appeared since C.F.A. Nobbes of 1843-1845; and while good translations of parts of the Geography have been produced in German and French, the only version in English has been the nearly complete, but in all other respects very unsatisfactory, translation by E. L. Stevenson.

The centerpiece of Ptolemys book is an enormous list of place names and coordinates that were intended to provide the basis for drawing maps of the world and its principal regions. A reliable translation of this part, and of another long section consisting of descriptions (or, as we prefer to call them, captions) of the regional maps, is unattainable in our present defective state of knowledge of the manuscript tradition of the Geography. These passages are in any case not designed for continuous reading, and we believe that most readers will not be disappointed to find them represented here by a description and a representative excerpt.

The remaining chapters of the Geography, which we have translated in their entirety, may be read as a series of essays of varying length dealing with aspects of scientific cartography. The work has, however, a unity of purpose and design that is possibly easier to grasp when these theoretical sections are not overshadowed by the geographical catalogue.

In our introduction and notes, we have assumed that our likely readers will be varied: historians of science (and their students) wanting familiarity with a classic of science; historians of the ancient world, hitherto lacking convenient access to the work of its greatest mathematical geographer; and, finally, those geographers who are interested in the origins of their discipline. We are well aware, however, that the line between pleasing and offending these disparate groups is a thin one, and we can only take comfort in the closing words of Samuel Johnsons introduction to his edition of Shakespeare:

It is impossible for an expositor not to write too little for some and too much for others. He can only judge what is necessary by his own experience: and how longsoever he may deliberate, will at last explain too many lines which the learned will think impossible to be mistaken, and omit many for which the ignorant will want his help. These are censures merely relative, and must be quietly endured.

This book had its beginnings at a time when one of us (AJ) was a student in the History of Mathematics Department at Brown University and the other (JLB) was there for a short visit. In the intervening years, the book took shape as each of us tested his contributions against the friendly skepticism of his coauthor. In addition, a number of individuals and institutions have helped over this time, and it is a pleasure to thank them here: Gerald Toomer, for suggesting the project and encouraging the authors to believe that they could handle it; Asger Aaboe, who, when he heard of the project, gave JLB his copy of Nobbes text of the work; Sarah Pothecary, for critically reading our early drafts; the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, the British Library, the Bodleian Library, the Houghton Library (Harvard University), the John Hay Library (Brown University), and the Newberry Library, for supplying microfilms and photographs of manuscripts; the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, for grants that made it possible for JLB to visit Brown University and to obtain photocopies of a number of rare printed editions of the Greek text of Ptolemys work; our home institutions, for unfailing support of our scholarly endeavors over many years; and our wives, for not only gracefully surrendering family time so that the work might progress, but also hosting visits by the co-authors for periods of concentrated work.

Note on Citations of Classical Authors

Where a standard division of a Greek or Latin author into books and chapters exists, we have used it, providing just the authors name when only one work is in question. For authors who have more than one established system for referencing, we have chosen the one that is in most common use. Thus passages of Strabos Geography are cited by book number, chapter, and section number, e.g., Strabo 2.5.5, rather than by the page numbers of Casaubon or Almaloveen that appear in some editions. For the readers convenience we have added page references to the translation in the Loeb Classical Library where one exists, and in the case of Ptolemys Almagest, to Toomers translation. Quotations are our own translations unless otherwise noted.

PTOLEMYS

Geography

Introduction

Ptolemys Geography is a treatise on cartography, the only book on that subject to have survived from classical antiquity. Like Ptolemys writings on astronomy and optics, the Geography is a highly original work, and it had a profound influence on the subsequent development of geographical science. From the Middle Ages until well after the Renaissance, scholars found three things in Ptolemy that no other ancient writer supplied: a topography of Europe, Africa, and Asia that was more detailed and extensive than any other; a clear and succinct discussion of the roles of astronomy and other forms of data-gathering in geographical investigations; and a well thought out plan for the construction of maps.

Ptolemy himself would not have claimed that the Geography was original in all these aspects. He tells us that the places and their arrangement in his map were mostly taken over from an earlier cartographer, Marinos of Tyre. Again, Ptolemy comprehended fully the superior value of astronomical observations over reported itineraries for determining geographical locations, but in this he was, on his own admission, anticipated by other geographers, notably Hipparchus three centuries earlier. Even so, he was too far ahead of his time in maintaining this principle to be able to follow it in practice, because he possessed reliable astronomical data for only a handful of places.