101 Things to Learn in Art School

101 Things to Learn in Art School

Kit White

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Kit White

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142.

This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Gotham Condensed by the MIT Press. Printed and bound in China.

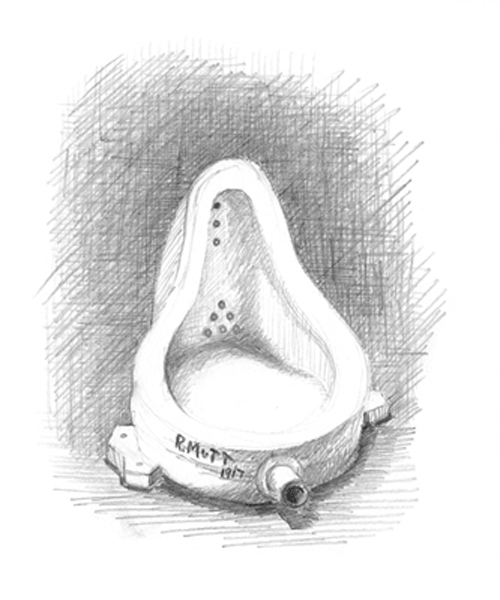

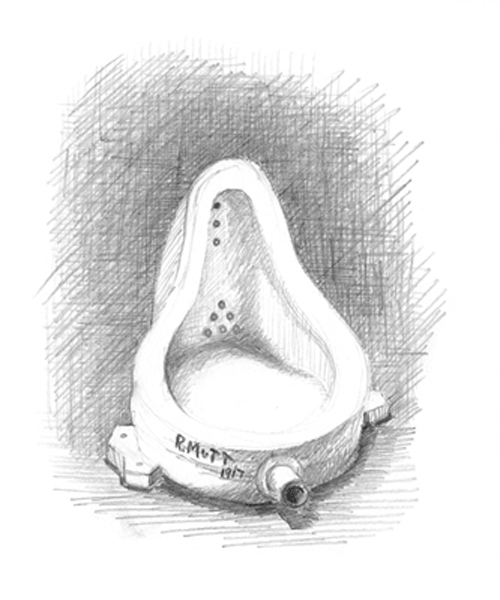

Cover illustrations based on Jeff Koons, Puppy, Bilbao, 19921994, and Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Kit, 1951

101 things to learn in art school / Kit White.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-01621-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-30013-1 (retail e-book)

1. ArtistsTraining of. 2. Art studentsPsychology. 3. Art schools. I. Title. II. Title: One hundred one things to learn in art school. III. Title: One hundred and one things to learn in art school.

N325.W49 2011

707.1dc22

2010047667

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Andrea and Philippa, who light up my days.

Author's Note

Art is an idea that belongs to everyone. It is found in every culture. Whatever physical form it might take, whatever emotional, aesthetic, or psychological challenge it may offer, it is vital to every cultures sense of itself. I have tried to keep this thought in mind as I developed the content of this book, for although art students and teachers might be its most natural readers, the practice of art, per se, is not a prerequisite to reading this book. Lessons learned in pursuit of art are lessons that pertain to almost everything we experience. Art is not separate from life; it is the very description of the lives we lead. And so, this book is really for everyone who cares about art and the way it enriches our being.

Humans have been producing art objects for tens of thousands of years, but art schools are a relatively recent phenomenon. Traditionally, artists received their training as apprentices to working artists or in ateliers presided over by a master. But the contemporary art school, as part of a larger liberal arts education, is an altogether different experience, reflecting the ways in which we have come to understand art as an extension of our daily culture. Art is everywhere. The way we make it, look at it, and analyze it is ever-evolving. It is that constant, ceaseless, becoming and transformation of art that has determined this books content; some of the lessons have to do with ways of making and representing, but just as many remind us of the necessity of searching, knowing, and doubting.

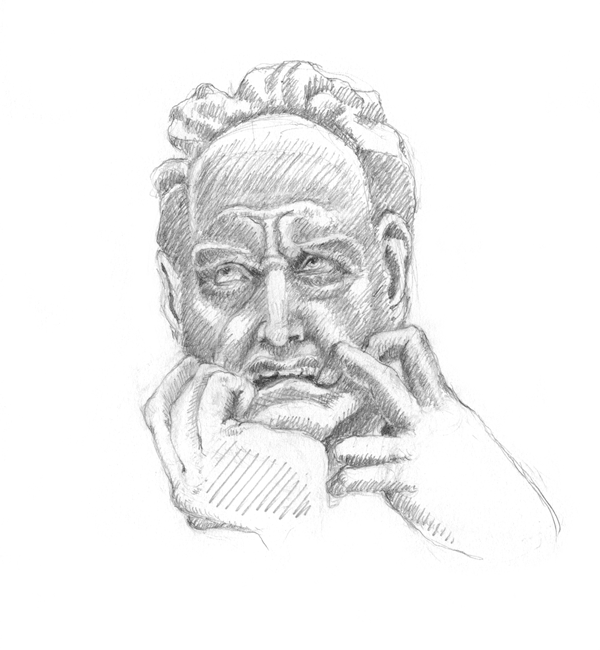

As a teacher, I still believe that technique has an important place in art education because artists are, at their core, makers. One has a different understanding of an image or object, how it does what it does, if one knows the details and processes of its creation intimately. This is one reason imitation has always been a part of artistic training. Artists assimilate a whole range of psychological, aesthetic, political, and emotional data points, and they then make forms to organize and give meaning to them. That takes skill and practice, working in tandem with intelligence and keen observation. But without the tools to fashion the form, it is like trying to capture air with a netand often about as effective. Basic form-giving skills help the student make the bridge between thought and embodiment. Because existing art is the best manifestation of artistic ideas, I chose to illustrate the lessons in this book with images based on historical and contemporary works of artto give each idea, lesson, or conceptual thing a visual correlative or apposite image. These drawings, with their imperfections and distortions, are mine, and as such they serve as demonstrations of what the words are largely about: how we learn through observing and attempting to capture ideas that were often originally and successfully executed by others. If my allusive drawings illustrate just how difficult it is to replicate the subtlety and nuance of another artists image, this should be taken as a humble acknowledgement of the difference between what a real work of art does and what an imitation accomplishes. These images are in no sense meant to be substitutes for the originals on which they are based, except for those that are my own work, or to imply agreement by the artists with the statements I have made. They are simply visual referrals to artists, ideas, and works that I believe art students should know and others might want to consider. Notwithstanding these qualifications, I am grateful that so many artists whose works I represented expressed their understanding and approval of my intent, and I appreciate their willingness to be my collaborators, in that sense.

When I was an art student, I never imagined becoming a teacher. I was focused only on becoming a maker. My feelings then mirrored the sentiment attributed to George Bernard Shaw, He who can, does; he who cannot, teaches. I discovered after a couple of decades of practice, however, that all of those critical, initial discussions that rose out of the need to know and the passion to do became increasingly less a part of the conversations I was having with my fellow artists. I missed the exercise of going back to the beginning, reexamining basic premises, asking first questions. As the ability to gain new perspectives at each turn in the road became more difficult, more distant, I began to reflect on the things we discussed in art school and on why those conversations should never stop. The issues we encounter as students of art are life lessons and should always stay with us. Without them, we are not students of life.

Kit White

March 2011

Acknowledgments

I had not entertained the idea of writing this book until Roger Conover suggested it to me. At first, the idea struck me as both impossible and challenging. I remained reticent until, after a few months of making notes, the project took on a life of its own, and I became intrigued by its possibilities. This book is a product of numerous conversations and debates with Roger, in person and at a distance, over several years. Throughout, his persuasion and support made this a true collaboration. My special thanks to Andrea Barnet, whose steadfast ear was always with me; William Fasolino, who showed me by example what it meant to be a dedicated teacher and who gave me my first opportunity to teach; Donna Moran, who opened many doors for me; my readers: Kurt Andersen, Jack Barth, Pier Consagra, Patricia Cronin, Rochelle Gurstein, Deborah Kass, Dana Prescott, and David True; William Strong, who guided me through the finer points of copyright; Deborah Cantor-Adams, whose diligence and careful eye assured the integrity of my text; Yasuyo Iguchi for her elegant design; Janet Rossi, who managed this books production; Anar Badalov, who responded to all queries before I could finish them; and especially all of my students, who have taught me far more than I have taught them.

After Marcel Duchamp

Art can be anything.

It is not defined by medium or the means of its production, but by a collective sense that it belongs to a category of experience we have come to know as art.