Contents

S HAMBHALA P UBLICATIONS , Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2018 by William Scott Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: The kamon of the Taira samurai clan, one of the eminent class of the Heian period (7941185).

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING-IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Names: Daidji, Yzan: 16391730, author.

Title: Budshoshinsh: essential teachings on the way of the warrior /

Daidji, Yzan; translated by William Scott Wilson.

Other titles: Bud shoshinsh. English

Description: Boulder: Shambhala, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018007794 | ISBN 9781611805680 (hardback)

eISBN9780834841703

Subjects: LCSH : BushidoEarly works to 1800. | BISAC: SPORTS & RECREATION / Martial Arts & Self-Defense. | PHILOSOPHY / Eastern. RELIGION / Confucianism.

Classification: LCC BJ971 . B8 D3513 2018 | DDC 170/.440952dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018007794

v5.3.2

a

L ord Somas family genealogy, called the Chiken marokashi, was the best in Japan. One year, when his mansion suddenly caught fire and was burning to the ground, Lord Soma said, I feel no regret about losing the house and all its furnishings, even if they burn to the very last piece, because they are things that can be replaced later. I only regret that I was unable to take out the genealogy, which is my familys most precious treasure.

There was one samurai among those attending him who said, I will go in and take it out. Lord Soma and all the others laughed and said, The house is already engulfed in flames. How are you going to take it out?

Now this man had never been loquacious, nor had he been particularly valuable, but he had been engaged as an attendant because he saw things through. At this point he said, I have never been of use to my master because Im so careless, but I have lived resolved that someday my life should be of use to him. This seems to be that time. And he leaped into the flames.

After the fire had been extinguished, the master said, Look for his remains. What a pity! Looking everywhere, they found his burned corpse in the garden adjacent to the living quarters. When they turned it over, blood flowed out of the stomach. The man had cut open his stomach and placed the genealogy inside, and it was not damaged at all. From this time on it was called the Blood Genealogy.

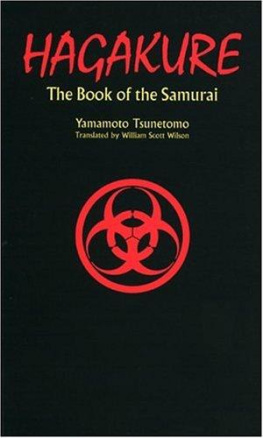

Y AMAMOTO T SUNETOMO , Hagakure, chapter 10

CONTENTS

PREFACE

B udshoshinshu and Hagakure are the most influential treatises on samurai philosophy from the Edo period. The two books were written at about the same time, and both addressed the warriors role in times of peace. While Hagakure was mostly a secret book of the Nabeshima clan until the twentieth century, Budshoshinshu was widely available almost from the start. Yamamoto Tsunetomo, the author of Hagakure, was an obscure samurai-turnedZen Buddhist priest and an avid student of poetry; his penchant for poetical style and themes can be observed throughout the book. By contrast, Daidoji Yzan, the author of Budshoshinshu, was descended from a long line of prominent warriors and was a well-known and sought-after teacher.

The writing of Tsunetomo, who entered the priesthood after retiring as a samurai, was clearly influenced by Zen Buddhism. Although Tsunetomo dwells as much on death as on the warriors duty, the connotation is that death of the ego is what allows the warrior to live and serve selflessly. Daidoji Yzan was a Confucian scholar, and although Budshoshinshu begins with a meditation on death, it is imbued with classic Confucian philosophy, centered on living ones life with sincerity and loyalty. The concept of living selflessly is the common thread that winds through both mens writings.

Many scholars consider Hagakure to be the most radical and romantic of samurai texts, while Budshoshinshu, owing to its heavy Confucian influence, is more measured and practical. Both texts are still widely available both in the original eighteenth-century Japanese and in modern Japanese renderings, attesting to their enduring appeal despite the enormous changes that have taken place in Japanese culture and society. Taken in tandem, they provide a range of insights on the role of the individual within the order.

W hat interest do discourses about samurai times and culture hold for todays reader? First, for those interested in Japanese and samurai history, primary sources such as these permit direct and valuable insight into the thoughts, ambitions, successes, and failures of these warriors of antiquity. The story of a castles destruction may read as just another lost battle, but the generals last letter to his son, explaining why the castle must fall and the general with it, brings to life the ideals that inspired his course of action. A feudal lords last testimony reveals the rationale for succession that ensured his clans longevity. These writings offer not just glimpses but sustained and enriching perspectives inside the events and politics of the day.

Second, although the warrior class eventually succumbed to the inexorable advance of mercantile spirit, samurai philosophy has persisted in Japanese consciousness up to the present. It is evident in many spheres of society, most obviously in the world of business. Those who have worked for Japanese companies will attest to this, though some might say that the warrior philosophy has been appropriated and adapted by the captains of industry to manipulate the workforce. But it is still one of the keys to understanding Japanese society and its impressive economic success.

Finally, the life of a samurai was imbued with meaning and purpose that often seem to be lacking from our own lives. The materialism and consumerism that are hallmarks of the contemporary world offer no vision or guidance for living, whether or not one aspires to the warriors life. Treatises on samurai thought impart ideals and values that seem to have been lost, and they offer reassurance about the significance of our lives and our choices.

H and-copied manuscripts of Budshoshinshu seem to have circulated to a number of clans not long after Daidoji Yzans death in 1730. It was first edited and published in woodblock print in 1834 by the Matsushiro clan. In 1943, Furukawa Tesshi published a new edition, based on a different manuscript, which is generally agreed to hew closer to Daidojis original. These two publications are organized differently, and the Matsushiro version tones down or eliminates some sections that contain radical notions. This translation is based on the Furukawa manuscripts.

My sincerest gratitude to the late Professor Noburu Hiraga, who originally guided me in this project; to John Siscoe, Tom Levidiotis, Gary Haskins, and Kate Barnes for their constant encouragement; to my wife, Emily, who reviewed the manuscript and offered helpful suggestions; and to Beth Frankl, John Golebiewski, and Jonathan Green at Shambhala Publications for helping to bring about this new edition.

INTRODUCTION

B etween the city of Nagoya and Mount Ibuki, there is a large plain called Sekigahara. Today it is scattered with rice fields and vegetable gardens, and skirted by the crowded Meishin Highway, which runs between Nagoya and Osaka. In the autumn, heavy mists collect over the area, making visibility poor, and cold winds are already tumbling down the mountain.