ABOUT THE BOOK The hermit-monk Ryokan, long beloved in Japan both for his poetry and for his character, belongs in the tradition of the great Zen eccentrics of China and Japan. His reclusive life and celebration of nature and the natural life also bring to mind his younger American contemporary, Thoreau. Rykans poetry is that of the mature Zen master, its deceptive simplicity revealing an art that surpasses artifice. Although Ryokan was born in eighteenth-century Japan, his extraordinary poems, capturing in a few luminous phrases both the beauty and the pathos of human life, reach far beyond time and place to touch the springs of humanity. JOHN STEVENS is Professor of Buddhist Studies and Aikido instructor at Tohoku Fukushi University in Sendai, Japan. He is the author or translator of over twenty books on Buddhism, Zen, Aikido, and Asian culture.

He has practiced and taught Aikido all over the world. Sign up to receive weekly Zen teachings from Shambhala Publications.  Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes. ONE ROBE, ONE BOWL The Zen Poetry of Rykan translated and introduced by John Stevens

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes. ONE ROBE, ONE BOWL The Zen Poetry of Rykan translated and introduced by John Stevens

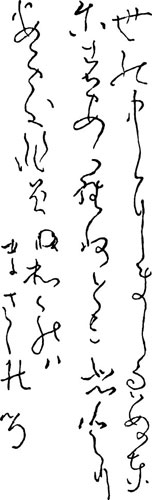

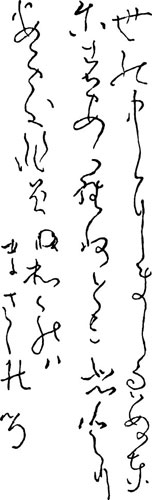

Weatherhill Boston London 2014 WEATHERHILL An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union. The cover design incorporates calligraphy by Rykan reading Mind, Moon, Circle, carved on the cedar lid of a rice pot.

Weatherhill Boston London 2014 WEATHERHILL An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union. The cover design incorporates calligraphy by Rykan reading Mind, Moon, Circle, carved on the cedar lid of a rice pot.

Courtesy of the Kera family, Niigata Prefecture. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUES THE PREVIOUS EDITION OF THIS BOOK AS FOLLOWS: Rykan, 17581831. / One robe, one bowl. / I. Title. / PL797.6.A281977 / 895.613 / 77-2405/eISBN 978-0-8348-2496-6/ ISBN 978-0-8348-0570-5 (pbk.) / ISBN 978-0-8348-0125-7/ISBN 978-0-8348- 0126-4 (pbk.) FOR JOYCE  Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems. / PL797.6.A281977 / 895.613 / 77-2405/eISBN 978-0-8348-2496-6/ ISBN 978-0-8348-0570-5 (pbk.) / ISBN 978-0-8348-0125-7/ISBN 978-0-8348- 0126-4 (pbk.) FOR JOYCE

Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems. / PL797.6.A281977 / 895.613 / 77-2405/eISBN 978-0-8348-2496-6/ ISBN 978-0-8348-0570-5 (pbk.) / ISBN 978-0-8348-0125-7/ISBN 978-0-8348- 0126-4 (pbk.) FOR JOYCE  Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems.

Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems.

After you know my poems are not poems, Then we can begin to discuss poetry! And, in autograph lines on a self-portrait sketch (see previous page): It is not that I do not wish to associate with men, But living alone I have the better Way. CONTENTS What will remain as my legacy? Flowers in the spring, The hototogisu in summer, And the crimson leaves of autumn. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1968, the late Yasunari Kawabata Both Kawabata and Suzuki felt that Rykan represents something very special in the Japanese character and that therefore all who wish truly to understand Japan should study the life and poetry of this eighteenth-century hermit-monk. From a religious standpoint also, Rykan is exceptional, exemplifying as he does the Zen Buddhist idea of attaining enlightenment and then returning to the world with a serene face and gentle words. In his life he was indeed Daigu, the Great Fool (the literary name he gave himself), one who had gone beyond the limitations of all artificial, man-made restraints. Rykan was born some time around 1758 (the exact date of his birth is unknown) in the village of Izumozaki in Echigo province on the west coast of Japan.

This area, now known as Niigata Prefecture, is rather remote even today, far removed from the commercial and cultural centers of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto. It is snow country and bitterly cold in winter. Rykans family was well established in the area, and his father, Tachibana Inan, was the village headman, the local Shinto priest, and a prosperous merchant. Rykans father was a complex person with a sensitive and passionate nature. He was a haiku poet of some note, with a certain following, but also an ardent imperial supporter and opponent of the bakufu, the military government in Edo. The reason for his unhappiness with the government is not clear (perhaps in his duties as village headman he had some clashes with bakufu officials), but when his son Yoshiyuki succeeded him (Rykan was the oldest son but turned his inheritance over to his brothers and sisters when he became a monk), Inan left home and spent many years wandering around Japan before settling in Kyoto.

He again declared his support of the emperor and, evidently feeling intolerably oppressed by the bakufu, committed suicide in 1795 by throwing himself into the Katsura River in Kyoto as a protest; he was sixty years of age. Little is known of Rykans mother, but it is clear from his poems concerning her that she was a very gentle and loving person. She died in 1783, and Inan left the village forever three years later. Rykans childhood name was Eiz. He was a quiet and studious boy who often spent long hours reading the Analects of Confucius. His family was well off, and the atmosphere in his home was a literary and religious onetwo brothers and one sister also entered the Buddhist priesthood.

His youth was calm and sheltered, and passed uneventfully until his eighteenth year. Rykan was to succeed his father as village headman when he turned eighteen. While training for the post, he found it especially trying. He was honest and conciliatory by nature and hated contention or discord of any kind, but was forced to deal with many conflicts and troublesome cases. In addition to those burdensome duties, he seems to have been undergoing some inner, spiritual crisis. Previously he had been a fun-loving young man, generous with his money and the center of attention at the local geisha parties, but he started to become withdrawn and silent in the midst of festivities.

Clearly something was troubling him, and he decided to become a Buddhist monk. In 1777 he shaved his head and entered Ksh-ji, the local Zen temple, where he took the name Rykan (ry means good; kan signifies generosity and largeheartedness). After he had trained there for about four years, a famous Zen priest known as Kokusen came to deliver a lecture. Kokusen was the abbot of Ents-ji temple at Tamashima in Bitch province (present-day Okayama Prefecture). Rykan was greatly impressed with Kokusen and decided to become his disciple and return with him to Ents-ji. Rykan was then twenty-two.

He trained under Kokusen at Ents-ji for almost twelve years. During this time he continued his studies of waka; Chinese poetry; linked verse, or renga; and calligraphy, becoming skilled in all of them. He was appointed Kokusens chief disciple and was given a document certifying his enlightenment in 1790. The following year Kokusen died and Rykan left Ents-ji to begin a series of pilgrimages that would last almost five years. After learning of his fathers suicide in 1795, Rykan went to Kyoto and held a memorial service for him. He then decided to return to his native village.

After searching for a time, he found an empty hermitage halfway up Mount Kugami, about six miles from his ancestral home. He named it Gog-an.

Next page

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes. ONE ROBE, ONE BOWL The Zen Poetry of Rykan translated and introduced by John Stevens

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes. ONE ROBE, ONE BOWL The Zen Poetry of Rykan translated and introduced by John Stevens

Weatherhill Boston London 2014 WEATHERHILL An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union. The cover design incorporates calligraphy by Rykan reading Mind, Moon, Circle, carved on the cedar lid of a rice pot.

Weatherhill Boston London 2014 WEATHERHILL An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union. The cover design incorporates calligraphy by Rykan reading Mind, Moon, Circle, carved on the cedar lid of a rice pot. Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems. / PL797.6.A281977 / 895.613 / 77-2405/eISBN 978-0-8348-2496-6/ ISBN 978-0-8348-0570-5 (pbk.) / ISBN 978-0-8348-0125-7/ISBN 978-0-8348- 0126-4 (pbk.) FOR JOYCE

Rykan has said: Who says my poems are poems? My poems are not poems. / PL797.6.A281977 / 895.613 / 77-2405/eISBN 978-0-8348-2496-6/ ISBN 978-0-8348-0570-5 (pbk.) / ISBN 978-0-8348-0125-7/ISBN 978-0-8348- 0126-4 (pbk.) FOR JOYCE