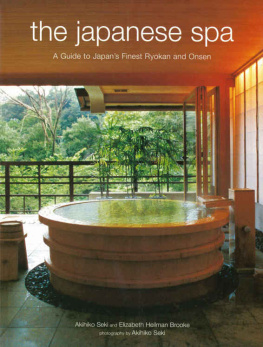

the Japanese Spa

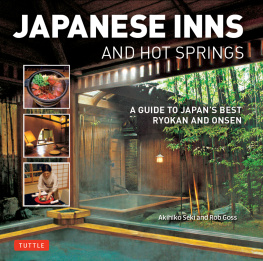

A Guide to Japan's Finest Ryokan and Onsen

Akihiko Seki and Elizabeth Heilman Brooke

photography by Akihiko Seki

contents

Around Tokyo

Gora Kadan

Tsubaki

Atami Sekitei

Kona Besso

Yagyu-no-Sho

Seiryuso

Senjyuan

Bankyu Ryokan

Sanraku

Kyoto and Nara

Hiiragiya

Seikoro Inn

Kikusuiro

Central Japan

Ryugon

Yumoto Choza

Wanosato

Kayotei

Araya Totoan

Houshi

Northern Japan

Mukaitaki

Saryo Soen

Tsuru-no-Yu

Kuramure

Southern Japan

Sekitei

Yamatoya Besso

Murata

Miyazaki Ryokan

Yusai

Gajoen

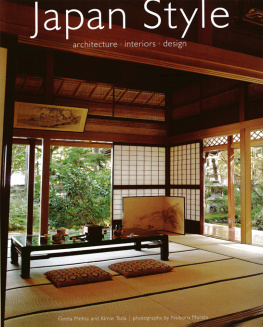

The Japanese Ryokan: A Timeless Retreat

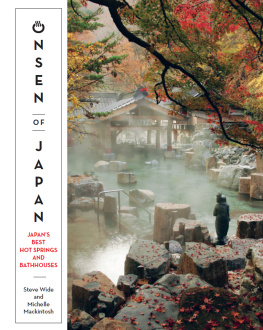

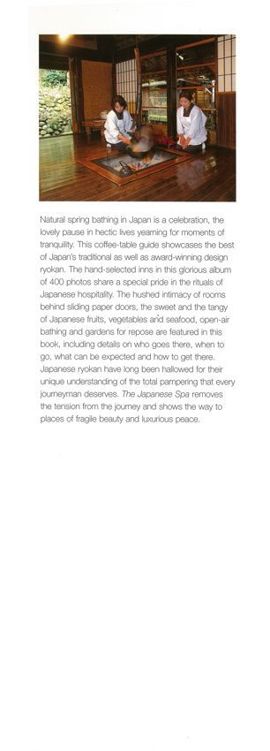

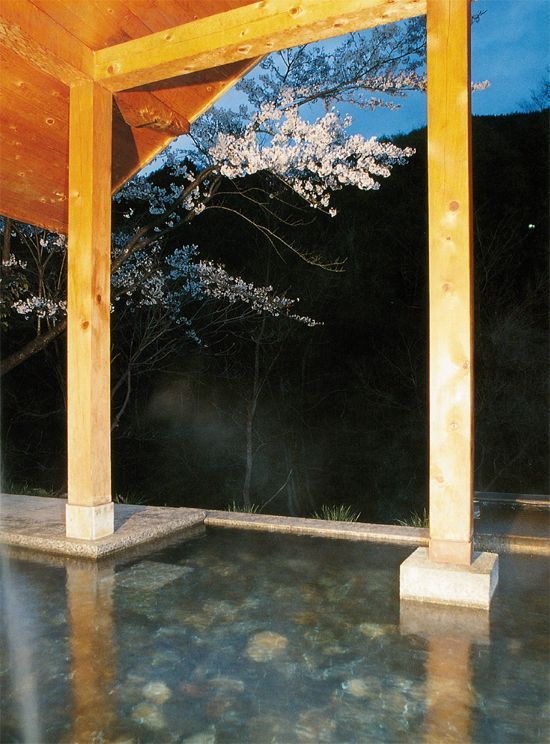

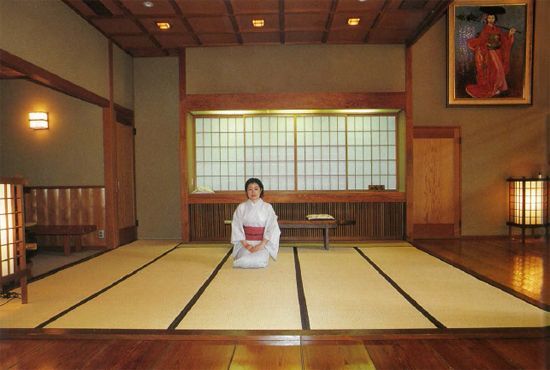

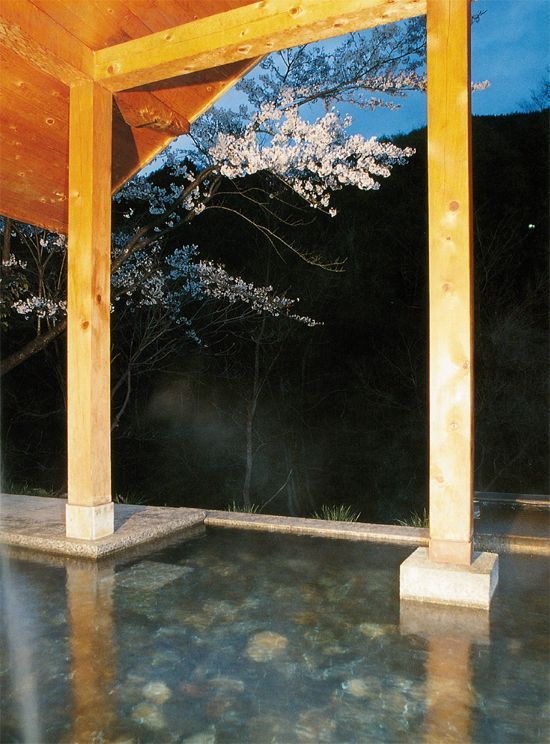

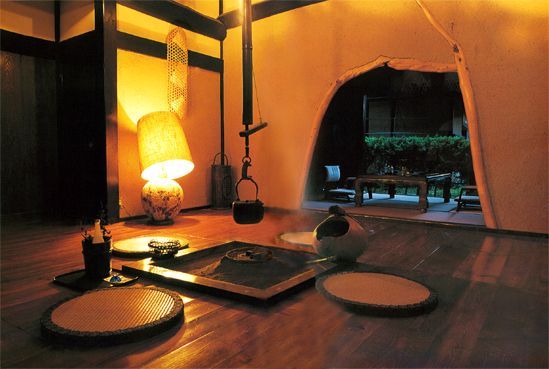

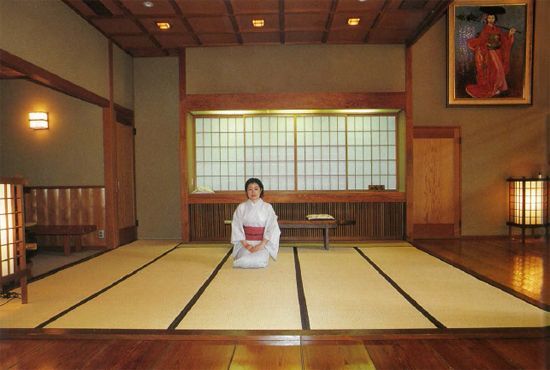

Slip off your shoes and enter a world that is distinctly Japanese. Cherry blossoms. Zen. Foamy green tea. Warm water meditations one might call, simply, a bath. Hospitality of honor. Ritualized routines to quiet, to sooth the mind, the spirit.

The philosophers, the potters, the tea masters and the poets of Japan, who, thousands of years ago halted the elaborate evolutions of beauty in all its sumptuous gold-leaf manifestations, have attracted generations of humbled aesthetics. Van Gogh, Picasso and Frank Lloyd Wright are among the many painters, architects and creative iconoclasts who have looked to Japan for inspiration. Free spirits have marveled at Japans studied serenity and heightened awareness of the beauty of a single blade of grass, a single flower petal, a single wave, a single volcanic mountain. They have studied wood, earth and stones, lines, planes and space, and mans daily interaction with the impermanence of nature.

A Japanese Zen monk once described absolute beauty as "pure white snow in a silver dish." This crystalline perception of beauty, the distilled, asymmetrical, modest interpretations of Japanese art and architecture that now are emulated around the world are no longer easy to find in Japan. A 21st century traveler to Tokyo must visually edit telephone wires, construction cranes, a wealth of concrete box buildings, concrete mountain faces, neon, plastic and florid representations of nature in ersatz form.

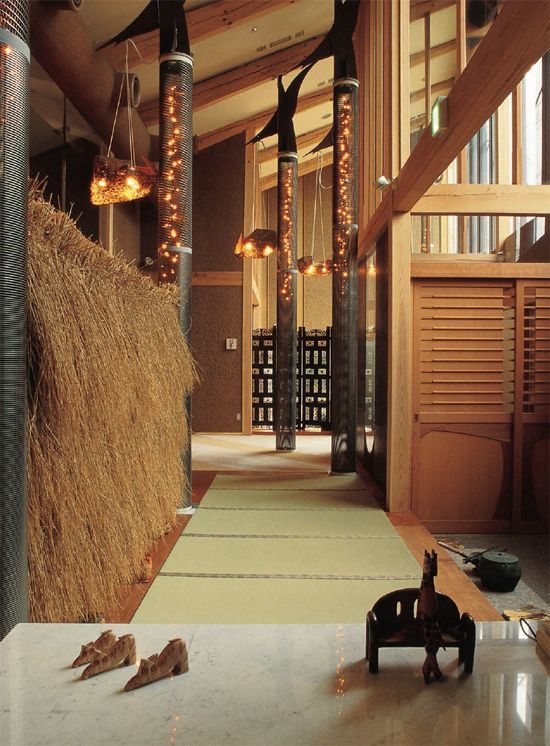

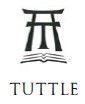

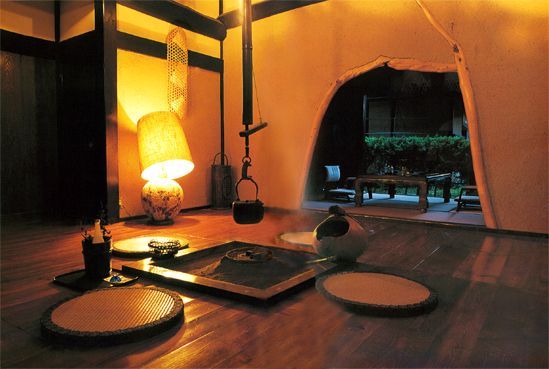

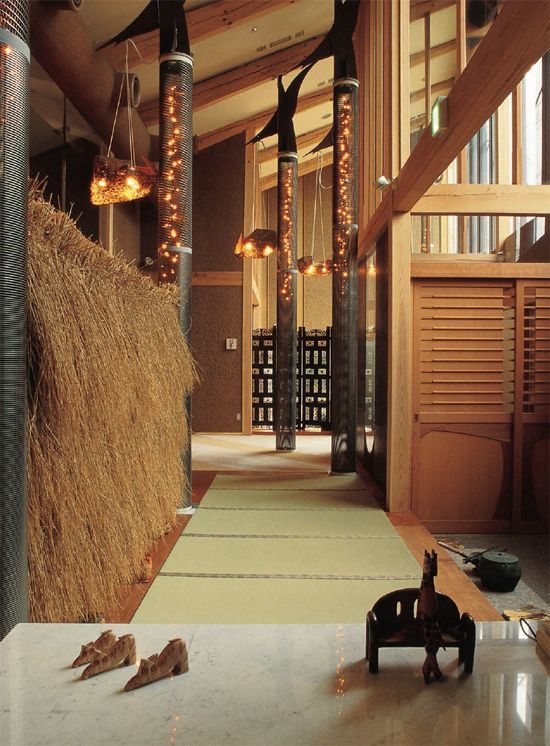

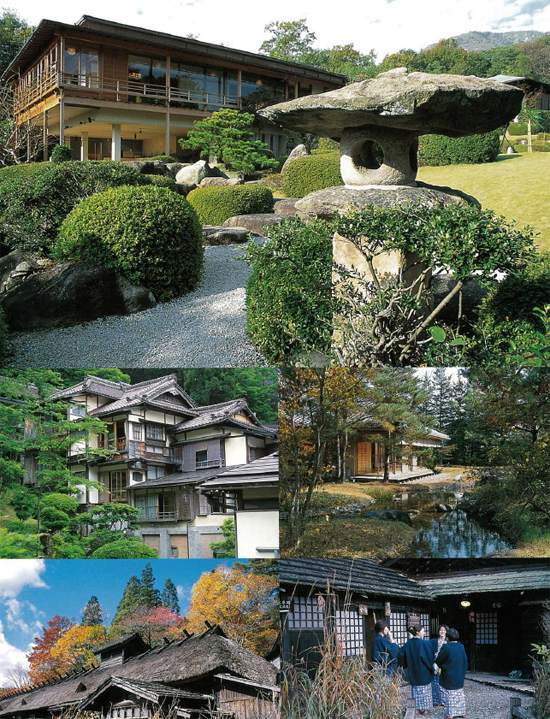

The good news is that even the Japanese have begun to look for spaces that are authentic, organic, human, historic, refined and natural. There are classic inns throughout Japan that have maintained and refreshed their thatched roofs, their bold wood beams, their fragrant tatami floors. And there are innkeepers, who, thankfully, have saved farmhouses, samurai and lordly residences, sometimes moving them and adapting them to accommodate modern-day guests. There are also recently built inns that are prize-winning in design, progressive in their reverence for the use of natural materials, old-world traditional in their concern for showing foreign visitors the unique rituals of a night spent at a Japanese inn.

It long has been lamented that Japan is still backward in opening doors and receiving foreign guests in a way that does not offend host and guest alike. That too is changing. The rigid formality, the total inability to communicate in any language other than Japanese and the abstruse dance of shoes and slippers and bowing and bathing costumes are no longer the norm in Japan. At last, self-conscious Japan recognizes that the international community treasures all that is special about Japanese hospitality and culture, yet requires more interpretation to access Japans less traveled paths. The Japanese government has launched a multi-million-dollar campaign, Yokoso! Japan, to welcome overseas visitors and encourage Japanese innkeepers and restaurateurs to translate some of Japans mysteries for a wider audience.

With an eye for the beauty of shadow, color and texture, bilingual photographer Akihiko Seki has spent two years traveling Japan in order to select and visually capture his favorite Japanese inns and spas. He has tried to visit each inn with the wide-eyed anticipation of a foreigner, who might speak little Japanese and know little of the context of Japanese inn-keeping and hot spring visiting.

Sekitei, across from Miyajima, is a garden of peace overlooking the Inland Sea; Saryo-Soen in Sendai, a boutique ryokan on six-and-a-half acres in the Akiu Onsen region; Edo elements remain alive at Tsuru-no-Yu in Akita, an inn popular with hikers, history buffs and bathers; Tsuru-no-Yu is one of Japans most refreshingly authentic retreats; Built in 1873, Mukaitaki in Aizu-Wakamatsu makes guests feel like their futon are floating among the trees.

Murata, on the east coast of Kyushu at Yufuin Onsen, a "petit" onsen ryokan of century-old farmhouses with open, airy spaces of Western and Eastern comfort.

The Kayotei Inn in Ishikawa offers highly attentive service and Sukiya-style beauty at its most understated elegance.

Light-years away from a hotel, a motel, a love hotel, or a capsule hotel, a ryokan is a traditional Japanese inn that can be found nearly anywhere in Japan. Ryokan are most often found in settings of historic significance or luxuriant natural beauty. They have clung to history, architecture, art and ways of doing things, and are thus usually preferred by foreign guests as excellent backdrops for studying and experiencing all that is different about Japan.

Peddlers, couriers, pilgrims and loyal lords to the Tokugawa shogunate of the 17th century were among the first streams of travelers in need of a roof and a hearth for the night. Every other year, daimyo ("local lords") were required to verify their commitment to the shogun by presenting themselves in what was then called Edo, Tokyo. Understandably, lodgings along the Tokaido highway linking Kyoto to Tokyo popped up, and soon there was a class system regulations for them as well. For court nobles and highly regarded samurai, there were honjin with formal gardens, decorated rooms, tatami-covered daises for visiting lords and hidden exits for guests in need of quick escapes from their enemy. Waki-honjin and hatagoya were for less-esteemed samurai, servants and other wayfarers of the day.

Check-in involved some bowing and tying up of one's horses. Guests usually went into the nearest town for dinner and female "companionship." The Tokugawa shoguns decided that it was time for some regulating of the night and declared that inns must serve dinner. There went the excuse to prowl around town. So, female courtesans began to bring their demure entertainments to the inns. Breakfast became another inn service, and the tradition of including dinner and breakfast with a nights lodging has remained a unique element of ryokan hospitality to this day.