`I'1

ne

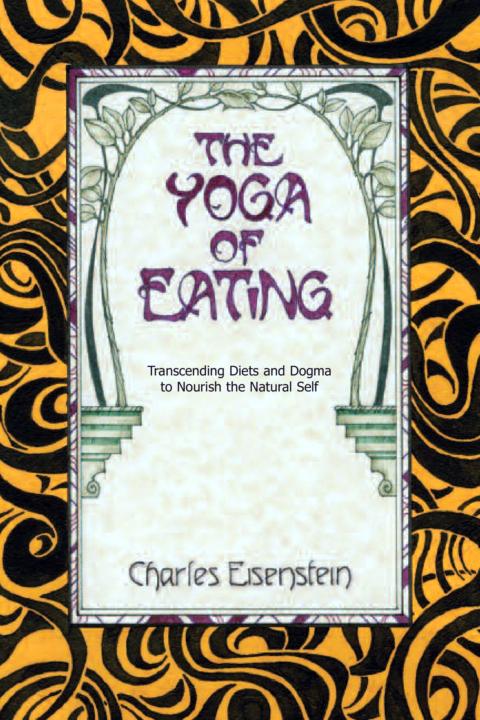

`Yalta af'Tating

Tie

`Yalta af'Tating

Transcending Diets and Dogma

to Nourish the Natural Self

Charles Eisenstein

I must have been incredibly simple or drunk or insane To sneak into my own house and steal money, To climb over the fence and take my own vegetables. But no more. I've gotten free of that ignorant fist That was pinching and twisting my secret self.

Jelaluddin Rumi

Yueh: "to please" or "to delight in." The leftmost three strokes comprise the symbol for heart, while the symbol on the right means to redeem, whether cashing a check or fulfilling a promise. Together they mean to redeem what's in the heart, to appropriately match what's outside with what's inside, and thereby to take delight in the world.

Contents

Chapter 1 3

Chapter 2 7

Chapter 3 11

Chapter 4 15

Chapter 5 27

Chapter 6 31

Chapter 7 41

Chapter 8 49

Chapter 9 57

Chapter 10 63

Chapter 11 71

Chapter 12 77

Chapter 13 83

Chapter 14 89

Chapter 15 95

Chapter 16 103

Chapter 17 109

Chapter 18 117

Chapter 19 123

Chapter 20 131

Chapter 21 135

Chapter 22 139

Chapter 23 143

Introduction

If you are like most people, at some point in your life you will decide to improve your diet. Inspired perhaps by a health crisis or a spiritual awakening or a new relationship, you decide to eat in a healthier or more ethical way.

Unfortunately, sooner or later you are bound to discover that "improving your diet" is not as straightforward as you imagined. Buy any book on diet or nutrition and you'll find plenty of persuasive advice on what we should and should not eat. Pick up another book and you'll find equally persuasive advice in direct opposition to the first. What to do?

One book might tout the wonders of soy; another will warn us of its dangers. One book might advocate a diet consisting primarily of raw foods, rich in enzyme vitality; another advises to limit intake of raw foods, so as not to dampen the digestive fire. One book will champion honey as a super-food; another says honey is just as harmful as any other sugar. Most mainstream books on nutrition advise us limit intake of fat, particularly saturated fat; an increasingly prominent minority contends that actually, traditional animal fats are good for you. Some authorities say that supplements are absolutely essential for good health; others say they just give you "expensive urine." One philosophy might advocate a diet based on your blood type; another, based on your ayurvedic type; another, on your Chinese medicine element. Some ethical systems are based on vegetarianism, others on localism, others on specific social or environmental issues.

The examples are endless. The hapless health-food explorer faces a bewildering thicket of contradictory advice, all coming from authoritative sources. Is there one diet among them that represents the True Gospel of health-choose rightly and you are saved, choose wrongly and you'll go to health Hell? If so, how do we distinguish it from among the hundreds of other diets on offer? Or maybe they are all correct, somehow, despite their blatant contradictions. Or maybe none of them are right.

Faced with this dilemma after a decade of dietary exploration and self-experimentation, I decided to try something different. Instead of trusting any outside authority, I would trust my own body-no matter what it led me to. This decision opened up whole realms of realization and discovery: about the untapped potential of the body and its senses, about the relationship between our manner of eating and manner of being, and about the spiritual aspects of our corporeal selves. Most importantly, my practice, which I call the Yoga of Eating, freed me to enjoy, for the first time in memory, the uninhibited pleasure of food accompanied by a growing wellness and physical vitality.

I use the word "yoga" in a very general sense, to mean a practice that brings one into greater wholeness or unity. The Yoga of Eating I describe is quite distinct from "yogic diets" advocated in popular books on Hatha Yoga. I will not tell you what to eat and not to eat.

This book, then, is not a diet book, nor is it a book on nutrition. Such books have their value, of course, but they must not be taken on anyone's authority-not even if this authority represents the full weight of scientific opinion. The purpose of this book is to introduce the reader to a higher authority: your own body. But why trust your body when it seems so often to lead you astray? How can we discern what our bodies are telling us? With these questions in mind, let us now explore the philosophy and practice of the Yoga of Eating.

Chapter 1

The Fallacy of Willpower

Those who restrain desire, do so because theirs is weak enough to be restrained; and the restrainer or Reason usurps its place & governs the unwilling.

- William Blake

See how many envelopes you can lick in an hour and in the next hour try to beat that record!

- Principal Skinner, The Simpsons

Many people despair at the prospect of improving their eating habits, because they think they just don't have enough willpower.

Not enough willpower. How else to explain destructive dietary habits even in full knowledge of the consequences? How else to explain pigging out all day after a week of disciplined eating? How else to explain snacking on donuts after having made an earnest, well-motivated pledge to give up donuts? It appears that willpower has failed, allowing a momentary compulsion to betray us.

Our society's appeal to willpower goes far beyond diet, of course. Often we seem to think that without willpower, we'd lounge around doing nothing all day, except to fulfill our nearest needs and pleasures. "What would you do tomorrow," I ask people, "if all of a sudden you lost all your willpower?" Most people imagine sleeping in, missing work, eating a big breakfast, and after that, a vague never-ending spiral of indulgence, indolence, and apathy.

Reliance on willpower reveals a profound distrust of one's self. We seem to think that what we really want to do must be bad, indulgent; therefore we must exercise willpower to enforce better behavior. Life becomes a constant regimen of "shoulds" and "shouldn'ts." But maybe this distrust is misplaced. Let's think about it more carefully: What if you really did lose your willpower tomorrow? Yes, maybe you would sleep in-but is that laziness, or a genuine need for rest? Maybe you would miss work-but couldn't that mean your work is not your soul's true work, and no longer do you force yourself to do it? You might stay in bed until ten, even until twelve, but eventually the bed would become uncomfortable. You might sit around doing nothing for a while, eating chocolate bon-bons and watching television, but eventually you'd become restless. Without work and chores to do, escapism loses its appeal. Maybe you'd feel free to catch up on neglected areas of your life. Maybe you would spend all day with your child, or a friend, or in nature. Maybe you would take up a creative project you'd never had time and energy to do. Maybe this creative project would turn into a new career, a job that you are excited to wake up to. Maybe, just maybe, life without willpower would be more creative, more abundant, more productive, and more dynamic than the life of shoulds and shouldn'ts.