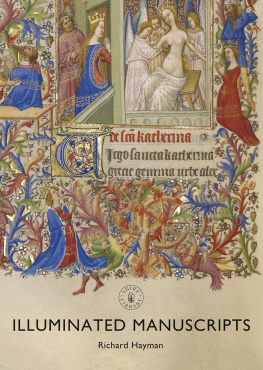

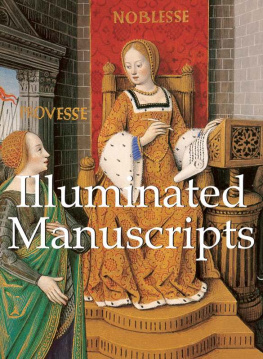

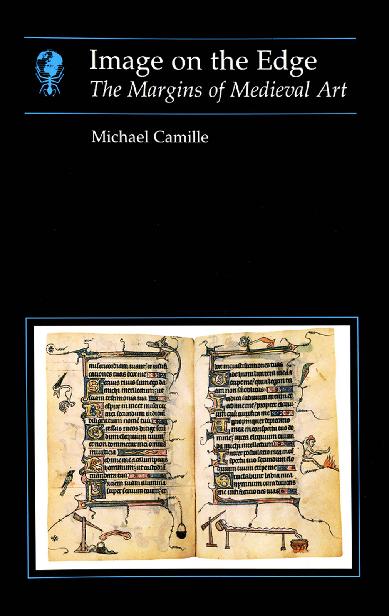

About this book This is the first book to deal historically and critically with the marginal art of the Middle Ages. For medieval people the margins were places of transformation and paradox, pun and perversity, areas in which social and psychological conflicts could be played out. From the often impudent antics pictured on the edges of prayer-books to the obscene, mocking gargoyles on the exteriors of churches, medieval image-makers focused attention on the excluded, the ejected and the antithetical.

After describing how the marginal art of both devotional and secular manuscripts served to gloss, parody or in other ways problematize the authority of the written word, Michael Camille explores the edges of the major social spaces of the time those of the monastery, the cathedral, the court and the city. By looking at the way marginality functioned in medieval culture, the author shows how these irruptive forms of marginal art were sustained by the absolute hegemony of the system they sought to subvert.

About the author Michael Camille has been an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Chicago since 1986, before which he was a Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. His book on The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art was published in 1989. He is currently at work on a book about images of the body in medieval society.

ESSAYS IN ART AND CULTURE

In the same series

The Landscape Vision of Paul Nash

by Roger Cardinal

Looking at the Overlooked:

Four Essays on Still Life Painting

by Norman Bryson

Charles Sheeler and the Cult of the Machine

by Karen Lucic

Portraiture

by Richard Brilliant

C. R. Mackintosh:

The Poetics of Workmanship

by David Brett

Image on the Edge

The Margins of Medieval Art

Michael Camille

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Limited

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC V DX , UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 1992

Copyright Michael Camille 1992

All rights reserved

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgments and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Designed by Humphrey Stone

Photoset by Rowland Phototypesetting Limited

Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Jolly and Barber Limited

Rugby, Warwickshire

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Camille, Michael

Image on the edge: the margins of medieval art. (Essays in art and culture) I. Title II. Series 709.02 e ISBN : 9781780232508 Contents

Acknowledgments

In addition to all the staff of those manuscript libraries and museums in Europe and the United States in which I have spent days on end on the edge, I would like to thank those friends, colleagues and students who have discussed the periphery with me: Lilian Randall, Lucy Sandler, Robert Nelson, Linda Seidel, Eugene Vance, Stephen G. Nichols, R. Howard Bloch, Malcolm Jones, Jonathan Alexander, Ross G. Arthur, Nurith Kenaan-Kedar, Jerry Dodds, Paula Gerson, Sarah Hanrahan, Ben Withers and Rita McCarthy. A special thanks to Mitchell Merback for help with compiling the Bibliography.

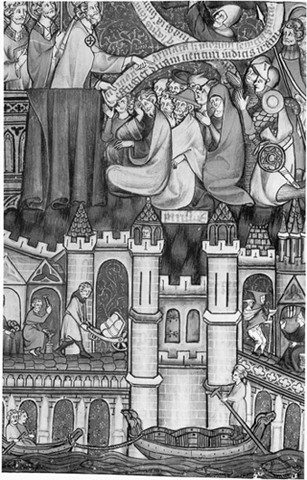

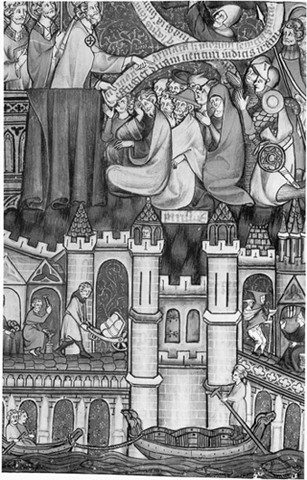

1 Beggars on the bridges of medieval Paris (detail of )

Preface

I could begin, like St Bernard, by asking what do they all mean, those lascivious apes, autophagic dragons, pot-bellied heads, harp-playing asses, arse-kissing priests and somersaulting jongleurs that protrude at the edges of medieval buildings, sculptures and illuminated manuscripts? But I am more interested in how they pretend to avoid meaning, how they seem to celebrate the flux of becoming rather than being, something I am able to suggest only in the completed sentences and sections of these essays. Nevertheless, my heteroclite combination of methodologies, aping those of literary criticism, psychoanalysis, semiotics and anthropology, as well as art history, is an attempt to make my method as monstrous (which means deviating from the natural order) as its subject. As was noted by Arnold Van Gennep, one of the first anthropologists of the edge, the attributes of liminality are necessarily ambiguous since [they] elude or slip through the network of classifications that normally locate states and positions in cultural space.

My opening chapter examines the cultural space of the margins and explores how it came to be constructed and colonized with such creaturely combinations during the thirteenth century. Images in the margins of Gothic manuscripts have been studied before, most notably by Lilian Randall. But rather than looking at the meaning of specific motifs, which are often reproduced as isolated details, I shall focus on their function as part of the whole page, text, object or space in which they are anchored.

The subsequent chapters focus on the margins of specific sites of power in medieval society monastery, cathedral, court and city. These spaces, although controlled by specific groups monks, priests, lords and burghers served more than a single audience. They were arenas of confrontation, places where individuals often crossed social boundaries. At a monastery or cathedral, for example, the fringes are where we find ejected forms, taboos sculpted in stone that seem to intensify the very desires they delimit. In courtly society, where the same bodily impulses were to some extent legitimated by a class ethos of pseudo-sacred chivalry and idealized in new genres, such as Romance, the marginal was rather a mode of entertainment or a means of subjugating the lower orders.

My chapter on the medieval city focuses on the visual representation of the subjugated rabble of urban marginals beggars and prostitutes. It also raises the crucial question of whether or not medieval artists, who increasingly worked in an urban context and portrayed themselves in the margins of their own images, were ever able to do more than play at subversion. Do the margins represent the beginnings of autonomous artistic selfconsciousness, as many have claimed? Finally, I will glance at the demise of the Gothic tradition of marginal image-making, which coincided with the rise of illusionistic space in fifteenth-century manuscript painting.

While an examination of marginal art is timely, considering current critical debates over centre and periphery, high versus low culture and the position of the other or minority discourse in elitist disciplines such as art history, we must be careful not to think of the medieval margins in Postmodern terms. During the Middle Ages the term marginal denoted, above all, the written page. The efflorescence of marginal art in the thirteenth century has to be linked to changing reading patterns, rising literacy and the increasing use of scribal records as forms of social control. Things written or drawn in the margins add an extra dimension, a supplement, that is able to gloss, parody, modernize and problematize the texts authority while never totally undermining it. The centre is, I shall argue, dependent upon the margins for its continued existence. For this reason I hope my book will stimulate many annotations, additions, queries and even, perhaps, one or two doodles of disagreement from its readers, eager to make images on the edge.

1 Making Margins

The men of the Middle Ages participated in two lives: the official and the carnival life. Two aspects of the world, the serious and the laughing aspect, co-existed in their consciousness. This co-existence was strikingly reflected in thirteenth and fourteenth-century illuminated manuscripts... Here we find on the same page strictly pious illustrations... as well as free designs not connected with the story. The free designs represent chimeras (fantastic forms combining human, animal and vegetable elements), comic devils, jugglers performing acrobatic tricks, masquerade figures, and parodical scenes that is, purely grotesque carnivalesque themes... However, in medieval art a strict dividing line is drawn between the pious and the grotesque; they exist side by side but never merge.

Next page