Goldstine Herman H. - The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann

Here you can read online Goldstine Herman H. - The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1972, publisher: Princeton University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann

- Author:

- Publisher:Princeton University Press

- Genre:

- Year:1972

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Adele | But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, |

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

Copyright 1972 by Princeton University Press

New preface 1993 Princeton University Press

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Card No. 70-173755

ISBN 0-691-08104-2 (hardback)

ISBN 0-691-02367-0 (paperback)

First Princeton Paperback printing, 1980

Fifth paperback printing, with a new preface, 1993

Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free

paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability

of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book

Longevity of the Council on Library Resources

10 9 8 7 6

Printed in the United States of America

(following page 120)

1. Reconstruction of machine designed and built in 1623 by Wilhelm Schickard of Tbingen. (PHOT: IBM)

2. Calculating machine built by Blaise Pascal in 1642. (PHOT: IBM)

3. Calculator invented by the philosopher Leibniz in 1673. (PHOT: IBM)

4. Difference Engine of Charles Babbage. (PHOT: IBM)

5. Automated loom of Joseph Marie Jacquard. (PHOT: IBM)

6. Difference engine built in 1853 by Pehr Georg Scheutz of Stockholm. (PHOT: IBM)

7. Lord Kelvins tide predictor. (PHOT: Reproduced by courtesy of the National Museum of Science and Industry, London)

8. Hollerith tabulating equipment used in the Eleventh Census of the United States in 1890. (PHOT: IBM)

9. The Michelson-Stratton harmonic analyzer. (PHOT: IBM)

10. The differential analyzer at the Moore School of Engineering, 1935. (PHOT: The Smithsonian Institution)

11. Harvard-IBM Mark I, the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator. (PHOT: IBM)

12. View of part of the ENIAC, the first electronic digital computer, operational in December 1945. (PHOT: The Smithsonian Institution)

13. Setting the function switches on the ENIAC. (PHOT: The Smithsonian Institution)

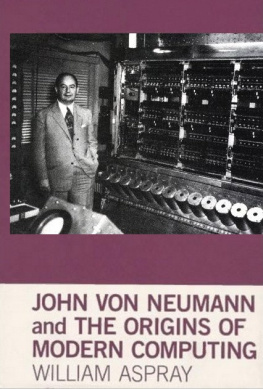

14. John von Neumann and J. Robert Oppenheimer at the dedication of the Institute for Advanced Study computer, 1952. (PHOT: Alan W. Richards)

It is now over twenty years since the first edition of this book appeared; in that period the world has been totally changed by the impact of the computer on our ways of thinking and acting. We all know, or at least sense, the many ways in which computer technology and its applications have modified our lives and ways of thought. They are so manifold that it would serve no useful purpose for me to detail examples here.

Before examining some of the changes, let us first see whatif anythinghas stayed invariant since the beginnings of the modern computer period. Perhaps most remarkable from our point of view is that the basic logical structure of the computer has by and large remained unaltered since its inception. This means that the logical design ideas discussed in this volume still have the same basic validity that they did when originally formulated.

Let us now look hastily at those things which have altered. Many of the enormous advances have been made possible by two marvelous technological developments: it was realized that the computer really processed information, not just numbers; and new hardware was invented that changed the entire inner economy of the computer, making it so inexpensive that it is now accessible to the average person, not just to the scientist.

The computers discussed in this book were based on a computing economy of very speedy arithmetic operations and very little speedy memory. This led to a need for numerical analytic techniques to suit that economy. Our numerical orientation dominated our thinking in the fields incipient days. Indeed, we envisioned the computer as the tool that would free people from the drudgery of scientific computation. This was the case, even though Alan Turing had already begun to move beyond the purely mathematical when he devised his well-known test to determine whether a human or a computer was responding to an interrogation.

This mathematical approach gave way during the decades since this book first appeared to informationally oriented points of view. Thus the world has moved into our present era both because of wonderful new technological advances in the form of cheap, powerful, and fast circuits and through the adoption of the simple idea that the key thing to process was information, not numbers. Thus the bit gave way to the byte.

We need to say just a few more words about our present computational environment, made possible by an incredible series of advances in technology: each year the price of a byte of memory has become so much cheaper that even the ubiquitous typewriter of James Barries The Twelve-Pound Look is now more properly found in a museum rather than an office. The so-called desk-top computer or PC is capable of doing virtually everything the typewriter could do and much more, at a comparable price; further, desk-top technology affects virtually every product we buy. Even our children in the earliest grades are using these instruments meaningfully. We are thus all participantswhether we like it or notin the Computer Revolution,

The other great realization has been that the basic structure of the computer, now known as the von Neumann architecture but described by Burks, von Neumann, and myself, is so powerful that many of the manifold tasks of the business world can be met by very efficient computers that greatly increase the productivity of virtually every employee in every store and company. It is only just now that we hear of the advent of highly parallel computers which represent a new architectural type, built up by yoking together concurrently many von Neumanntype machines. Such machines are not discussed in the succeeding pages. Although the ENIAC was also a parallel machine, these new machines represent an enormous step beyond it.

H.H.G.

Philadelphia, Pa.

March 1992

This work divides rather naturally into three parts. There is the preWorld War II era; the war period, particularly at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania; and the postwar years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, through 1957. I was concerned as a principal in the last two periods, and the reader will undoubtedly notice the stylistic differences that this has occasioned. It seemed to me in writing the text quite natural to record events as I viewed them then.

Of course, the writing of a history by a participant in the events is at best a tricky business since it may bring into the account some measure of personal bias. In mitigation it may be said, though, that it does provide a detailed, precise understanding of the people and of the events that actually took place. Such an understanding is very difficult for a non-participant. I therefore decided it was worthwhile to write this account with all the objectivity I could, with occasional warnings to the reader about possible traps awaiting him on his peregrination through the period.

There are, of course, at least two basic ways in which the history of apparatus can be written: by concentrating on the equipment or on the ideas and the people who conceived them. I have chosen rather arbitrarily to give the ideas and the people first place, perhaps because I find that approach more interesting personally. In any event, I have also tried to say enough about the apparatus to make it intelligible without becoming overly technical. The reader will find ever so often that the chronological narrative is interrupted by excursi in which I have attempted to explain some technical point so as not to leave the reader uninformed as to its nature. It is to be hoped that these interpolations do not unduly retard the account.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann»

Look at similar books to The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Computer from Pascal to Von Neumann and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.