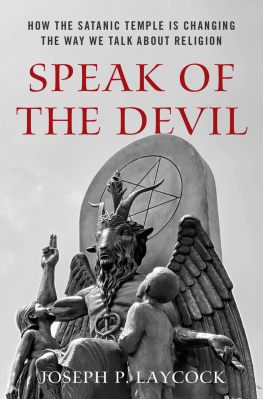

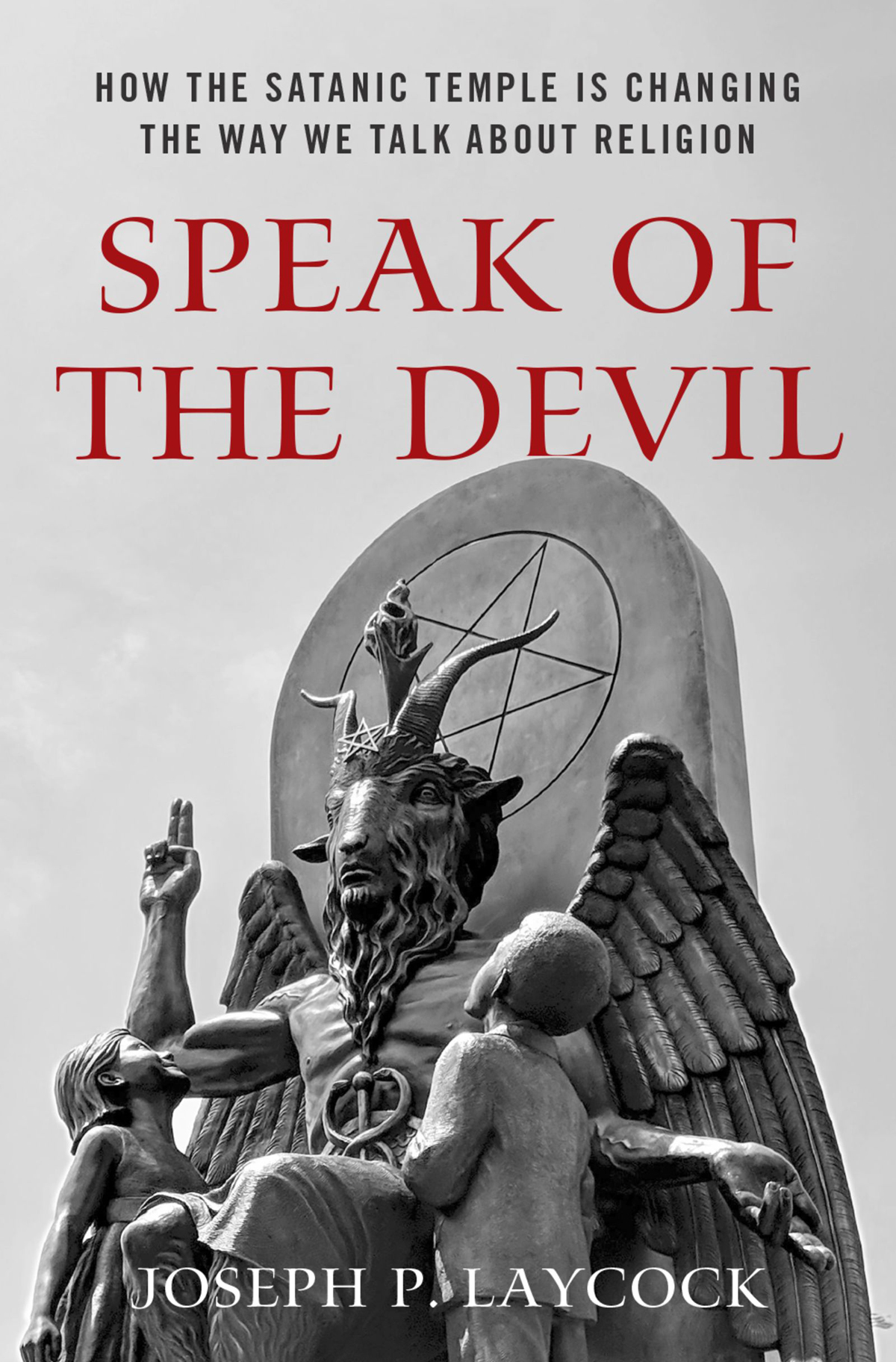

Speak of the Devil

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190948498

eISBN 9780190948511

For my alma mater St. Stephens Episcopal School, where I learned sympathy for the devil.

Contents

I am not now, nor have I ever been, a Satanist. But people have accused me of being oneboth as a middle schooler for playing D&D (Dungeons and Dragons) and doodling monsters in notebooks and as a scholar for writing a book about self-identified vampires. (Most vampires are not Satanists, but anti-Satanists have little use for nuance.) Perhaps it is because of these accusations that I was so interested when a group of Satanists offered to erect a statue of the devil next to a monument of the Ten Commandments. I have covered The Satanic Temple (TST) for Religion Dispatches and other news outlets since 2013. It wasnt that TST lacked for headlinesin the age of click bait, online media is madly in love with TST. But most of the coverage was and remains shallow, sensationalistic, and uninformed. Few outlets understood the constitutional issues at stake (or else grossly distorted them), and fewer still had any theoretical framework to think about TSTs assertion that they are, in fact, a religion.

TST grew so fast and did so much in its first six years that it took patient observers to keep track of what was happening. The canard that TST members are just trolls has, in part, served as a convenient way of shirking the hard work of sorting out just what this group does and why. Amazingly, even when lawsuits filed by TST began to move into circuit courts and I started receiving calls from attorneys and prison chaplains asking me to explain what TST is, some persisted in telling me that the whole thing was obviously just a PR stunt.

While the future of TST is far from clear, I think there are several reasons why it is worth understanding this group, its arguments, and its history better. First, as a professor of religious studies, TST is good to think with. Their provocations provide almost ideal case studies for classroom discussions precisely because they problematize our assumptions about religion and religious freedom. I have several colleagues who have asked their students to analyze TST for just this reason.

Second, TST is eliciting similar conversationsin a less organized and productive fashionon a national scale: the more their provocations are discussed, condemned, or even dismissed, the more unsettled previous assumptions about religion and religious freedom become. These are strange times: while exploring the discourse surrounding TST, I encountered skeptics professing a newfound appreciation for the value of religious ritual and community and conservative American Catholics openly denouncing the idea of religious freedom.

Third, TST seems to have played a major role in a global renaissance of religious Satanism. Since 2013 new Satanic organizations have formed throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. There are also rumors of groups forming in South America and the Middle East. Some of these emerging forms of Satanism are allied with TST and some are not; some reject supernaturalism as TST does, and some do not. But many of these groups have emulated TST in seeking a public platform and a degree of social engagement that is largely unprecedented in the history of religious Satanism. A decade ago, Satanists marching in gay pride parades, adopting highways, or running donation drives to aid the homeless would have been considered an absurdity. Today, such activities occur around the world.

This book, therefore, seeks to do two things. First, there is a need for a detailed history of TST. This history is short but far more complicated than the casual observer may suspect. The media has reported sporadically on TST, providing arresting headlines for their campaigns and provocations, but little context. I have already seen a number of legal and theoretical arguments put forward regarding TST, but without an understanding of what TST is or where it came from these arguments will be counterproductive. I have attempted to provide a history that is comprehensive if not exhaustive that includes details that might otherwise have been lost and arranges them into a coherent narrative.

Second, I hope to show how TSTs provocations are affecting our national conversation about important issues. TST punches above its weight due to its ability to draw media attention, its creative use of the legal system, and its tactical manipulation of its opponents rhetoric. Due to these factors, TST has a real effect on how we talk about religion, morality, and what a religiously plural democracy ought to look like. There is already a body of scholarly literature on religious Satanism, but I think TST shows why Satanism has wider implications and should be taken more seriously by religion scholars.

Researching this book took far longer than any project I have previously done. In order to see the full range of discourse surrounding TST, I set up a daily news alert for the word Satanic. Each morning I went through all the local news segments, blog entries, and editorials discussing TST. Working over a period of years, I created an archive of over 2,600 news items.

I did ethnographic observation with TST chapters in San Marcos and Austin, Texas, as well as in Salem, Massachusetts, and Little Rock, Arkansas. I also conducted research interviews with over fifty people spread across fifteen states as well as the United Kingdom and Australia. With many of these individuals there were second and even third interviews. Many people interviewed for this book use pseudonyms for safety reasons. I have tried as much as possible to protect the identities and privacy of my informants. Because TST often requires its leaders to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), I should mention that I never signed an NDA and was never asked to do so.

Several months into the ethnographic phase of my research, TST went through a major schism and several chapters left to become independent. As a scholar of new religious movements, it was an interesting experience to watch a religious group splinter before my eyes. While witnessing this was exciting from a pure research perspective, it was very painful for everyone involved. Several of my interview subjects exhibited signs of anxiety and depression, and at times I felt depressed myself. Some approached me for follow-up interviews about how they were feeling, and at times I felt more like a confessor than an ethnographer.