preface

I wasnt born a storm chaser. Like so many things in my life it came out of left field, without a warning or sign. My photography career was unusual in that I did not decide to become a professional photographer until I was thirty-two years old. I frankly had no idea that such a job was accessible to someone like mea woman of color from a family of little means. But audaciously I dared to dream. It all happened so quickly and with great fanfare. Before I knew it, magazines were publishing my work, I was winning awards, and my work was being exhibited in museums and galleries all over the country. In interviews I was inevitably asked about my next body of work, and I had no idea what it would be. My experience in the Arctic and Antarctic had happened so serendipitously that I began to worry that perhaps it was all I had in me as an artist, that maybe I was just a one-hit wonder.

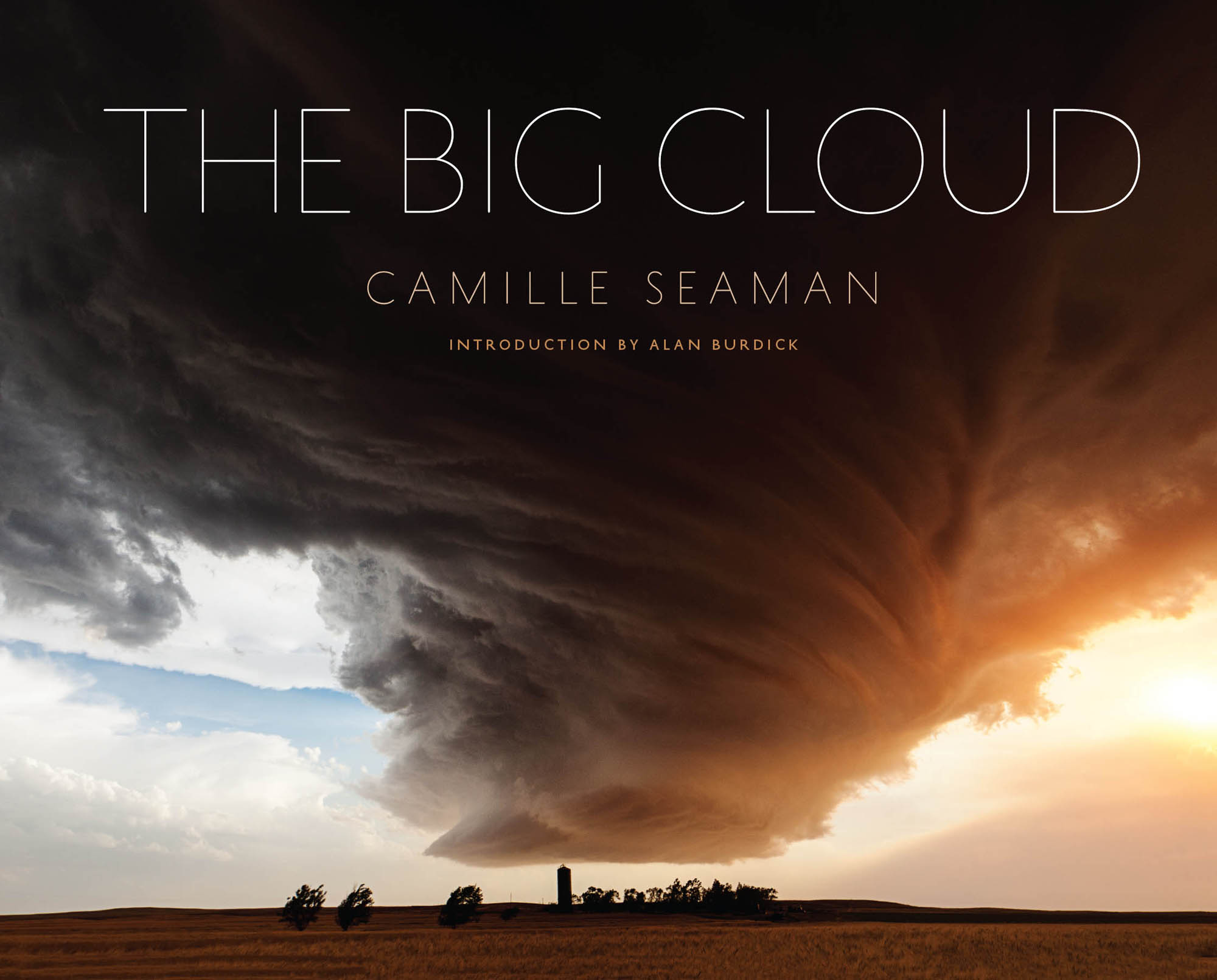

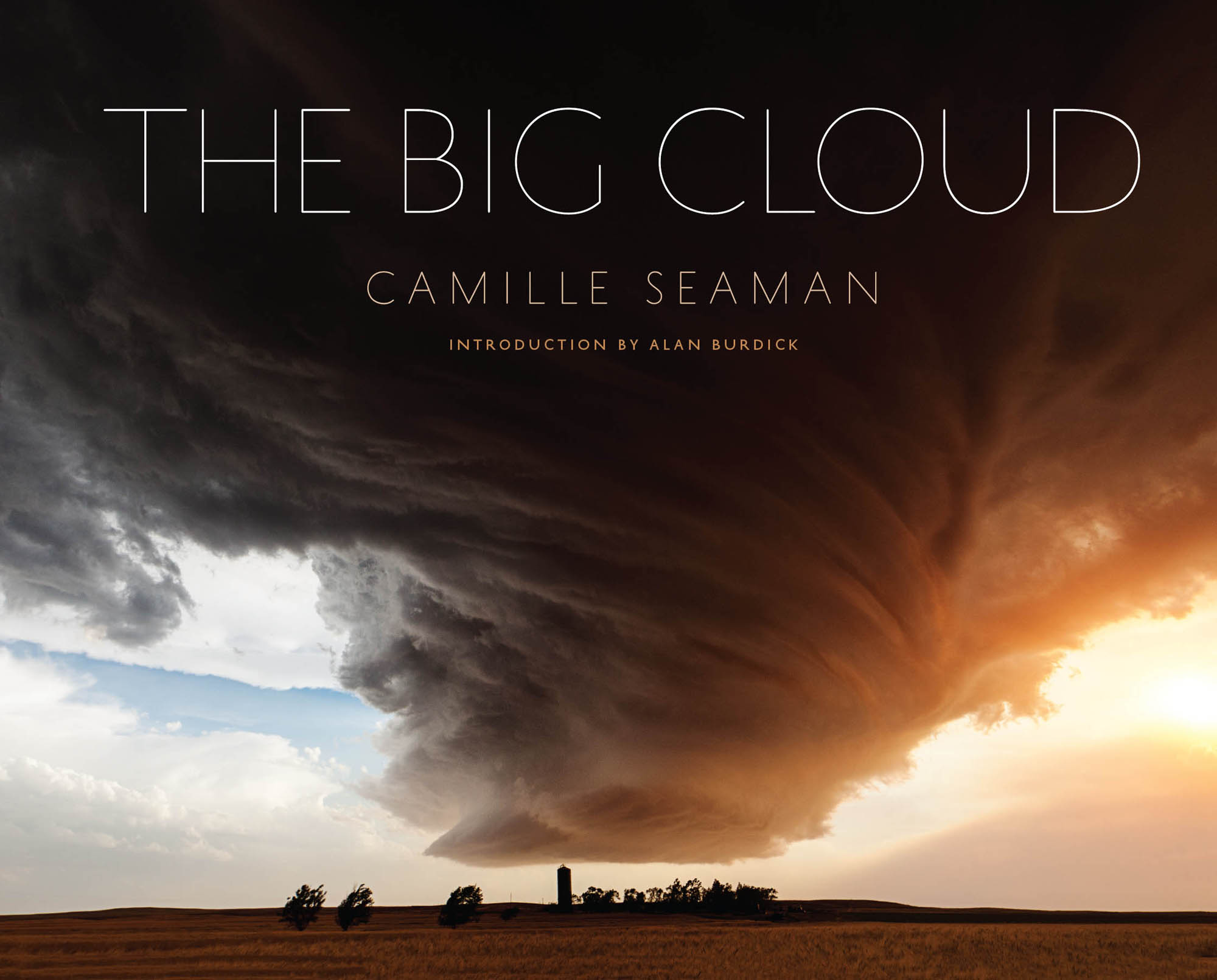

It was while I was vacuuming the living room one Saturday in our home in Berkeley that I saw the light, literally and figuratively, of storm chasing. My eight-year-old daughter sat on the couch watching Storm Chasers on the National Geographic channel. She caught me looking sideways trying to see into the TV. (I was wishing the videographer had a wider lens or that the camera would turn.) My daughter said, Mom, you should do that. It was so matter of fact. Yes, I said. So I googled storm chasing, and an entire world became visible to me that I had known nothing about only moments before. There were even companies that offered storm-chasing vacations for people to spend a week driving around looking for bad weather! One site stood out among the othersit had lightning flashing across the screen and thunder noises as a soundtrack. It was so nerdy (I know when to recognize passion when I see it) that I said to myself, This is the guy for me! I was terribly disappointed when I looked through the dates for the coming months only to find he was booked full. Not being one to give up so easily, I sent an email saying that I was very interested in chasing and to please let me know if anyone canceled. Less than an hour later he replied, asking if I could be in Oklahoma City in three days, as one spot had come available. So just three days after my daughter had said, Mom, you should do that, I found myself with five other individuals from all over the world hurtling down a US interstate chasing something called a supercell.

I wasnt prepared for just how overwhelming an experience chasing can be. It is visceral and multisensory: the smell of the charged particles, the sweetness of the grass, the scent of the pavement just before it rains, the sight of the wind blowing through cornfields. Not to mention the colors of the clouds and the light of the sky and the lightning. Its all so beautiful, so awesome, and so humbling at the same time. After that first week I was hooked, and at the end of the tour I asked if he would keep me in mind if any other cancellations occurred. He asked if I could drive, and I replied, Yes, I even have a commercial license. He hired me on the spot as his driver. In just one week I had transitioned from being a paying tourist to a professional storm chaser. Over the years I learned a great deal about the technical aspects and science as well as the lingo and culture of storm chasing.

Sometimes as we pulled into a local fuel station, we would be met with superstitious folks who were not glad to see us; some of those people had lost their homes or loved ones in storms. It was important to remember that these people lived here year after year, never knowing if this would be the day when a tornado might come through their town. It taught me great empathy and compassion. It was important that our chasing storms not become some sort of disaster tourism. My images were never about what these storms destroyed or the pain and damage they inflicted on the people of the region. I always wanted my images to speak to the duality of all thingsto speak to the essential truth that there can be beauty in something terrible and vice versa, that there is no creation without destruction.

introduction

alan burdick

A cloud is a shade in motion. Shape shifting and moody, it appears with a message that is opaque as often as it is threatening. Clouds always tell a true story, the Scottish meteorologist Ralph Abercromby wrote in 1887, but one which is difficult to read.

Early naturalists didnt know quite what to make of these apparitions. Aristotle saw them as the result of exhalations given off by the earth. (There were two kinds, either warm and moist or hot and humid.) In the seventeenth century Descartes concluded that clouds were made of water droplets or ice particles that ascend from the ground and as soon as they are joyned, rise up in little heaps, and these gatherd together compose vast Bulks. A leading theory into the nineteenth century held that clouds were made of tiny, bubble-like droplets that sunlight had filled with a lighter-than-air aura that enabled them to rise and stay aloft. One meteorologist and explorer claimed to have seen these entities, with inconceivably thin membranes and greater diameters than peas, floating in the mountain air.

The challenge in part was how to account for the constant change that clouds manifest. They are the very essence of dynamism, continuously dissolving and transforming. Maybe nomenclature could capture them. The faces of the Sky they are so many, that many of them want proper names, the English scientist Robert Hooke wrote in 1667. Hooke offered several, and later dozens, of classifications: Hairy clouds signified a Sky that has many small thin & high Exhalations which resemble locks of hair or flakes of hemp or flax; a Checkerd blew was a cleer Sky with many great white round clouds such as are very usuall in Summer. (Hooke also proposed, less helpfully, that its Cloudy when the Sky has many thick Dark cloudes.) In 1799 the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck distinguished five kinds of clouds, including pommels (dappled clouds), en balayeurs (broomlike clouds), and groups (grouped clouds). Through a series of annual almanacs he eventually made it twelve types, including torn clouds, banded clouds, and running clouds.

It was like trying to catch water with a net. Such efforts produced long lists of names that were as imprecise as they were descriptive, as if it were possible to give a name to every individual cloud in the sky. In 1803 Luke Howard, a British pharmacist, proposed a classification scheme that has mostly stayed with us. It introduced four basic kinds of clouds: cirrus, stratus, cumulus, and nimbus, the Latin words for curl, layer, mass, and rain. But it also proposed an array of sub-categoriescirrocumulus, cumulostratusthat recognized the fact that one kind of cloud could turn into another. Howard also acknowledged that clouds obey earthbound physics; they dont rise or float by their own power but are forever falling, kept aloft only by upward currents. Inspired by Howard, the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote a series of poems about clouds, including one to Howard himself: That which no hand can reach, no hand can clasp, He first has gaind, first held with mental grasp.

Next page