ALSO BY HENRY GEE

Deep Time: Cladistics, The Revolution in Evolution

JACOBS LADDER

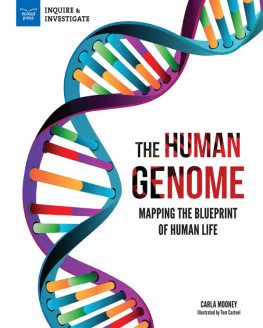

The History of the Human Genome

Henry Gee

W.W. Norton & Company New York London

Copyright 2004 by Henry Gee

First American Edition 2004

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

ISBN 0-393-05083-1

ISBN 978-0-393-24638-4 (e-book)

WW. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

WW. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it. And, behold, the Lord stood above it, and said, I am the Lord God of Abraham thy father, and the God of Isaac: the land whereon thou liest, to thee will I give it, and to thy seed; And thy seed shall be as the dust of the earth; and thou shalt spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north, and to the south: and in thee and in thy seed shall all the families of the earth be blessed.

Genesis 28: 1214

Wherein I spake of most disastrous chances,

Of moving accidents by flood and field,

Of hair-breadth scapes i the imminent deadly breach,

Of being taken by the insolent foe

And sold to slavery, of my redemption thence

And portance in my travels history;

Wherein of antres vast and deserts idle,

Rough quarries, rocks, and hills whose heads touch heaven,

It was my hint to speak such was the process

And of the Cannibals that each other eat,

The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Do grow beneath their shoulders.

Shakespeare, Othello, I, iii, 13445

On 12 February 2001, an international team of scientists announced that they had substantially deciphered the human genome the genetic instructions for creating and maintaining a human being, and our evolutionary birthright. The event was reported in the New York Times as an achievement representing a pinnacle of human self-knowledge. The effort to sequence the human genome has been compared with the Apollo programme to put astronauts on the Moon, so the scientists were surely entitled to a certain amount of self-congratulation.

To describe the sequencing of the genome as a technical feat like sending astronauts to the Moon, or even crossing the Himalayas on a unicycle is to miss the point. To be sure, it is fun to learn that if each one of the three billion DNA bases that make up the genome were magnified to the size of a letter on this page, the genome itself would stretch across the continental United States and back again. But such facts stupefy rather than edify. The genome is important not because of what it is made of, but because of what it does: it is the agency that creates and maintains an organism, urging an endless variety of exquisite life forms from formless eggs. As such, it transcends the particularities of its substance and becomes a motif that has been central to biological thought since antiquity, making the achievement of 2001 all the more profound and exciting.

If any discovery represents a pinnacle of human self-knowledge, it does so only by virtue of the support of the mountain on which that pinnacle is raised. For thousands of years, people have wondered about the identity of the mysterious and marvellous entity that makes babies, shapes our evolutionary history and populates the world with living things of almost unimaginable variety in short, the thing that teases form from the void. The history of biology can be retold as the story of the search for this agency, the genome. My aim in this book is to tell that story. Or rather, three stories.

The first, and the most direct, is an account of the intricate development of a human embryo from an egg. A pea-sized embryo recognizable as human develops from a fertilized egg in just four weeks, often before the mother even realizes she is pregnant. In this first strand can be seen the initial impetus for this book, which grew out of a desire to express the wonder that every new parent feels on confronting birth, an event which is both intimate and timeless.

The development of a human embryo is at the same time an expression of unique individuality and universal heritage. At this point the first story gives way to the second: how the course of individual development mirrors the history of human evolution itself, back to the dawn of life. Put another way, the human genome directs the development of every single embryo, but is itself a product of evolution and a reservoir of evolutionary memory.

The third story and the one around which the book as a whole has been constructed is the tale of discovery, of how people over many centuries have come to understand the development of individuals in terms of the variation, diversity and evolution of species.

As I researched the book, I found to my surprise that the story can be traced back to antiquity and extends more or less seamlessly down to the present. From a fully historical perspective, modern scientific research shows clear evidence of its ancient roots. For example, every scientist takes for granted that the genome in any particular individual, while unique to that individual, is at the same time the vehicle for our heritage. This is not a modern view, but stems directly from a theory which is now all but forgotten the theory of preformationism. This idea, which formed the mainstream of biological thought in the late seventeenth and for much of the eighteenth century, holds that the germ of each individual is not made anew with each conception, but was created in all its essentials at the beginning of time. In other words, conception does not start a new life from scratch, but simply activates a programme that was already in existence, and which has existed since the beginning of time. The modern idea of the genome as the eternal encapsulation of the instructions to produce a human being owes much to preformationism. Watson and Cricks classic paper from 1953 on the structure of DNA, containing the now famous line It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material, is pure preformationism.

To take another example: all modern evolutionary biologists are conscious of a link between the events in the development of any particular embryo and the shape of the history of the species to which that embryo belongs, and indeed the history of all life. Scientists now take for granted that there is a deep connection between embryology and evolution; and that the shapes of living organisms are not random, but display very clear patterns which are indicative of a shared evolutionary relationship. This insight emerged during the era of romanticism at the turn of the nineteenth century, and found scientific expression in a movement known as nature-philosophy, which saw human development as an expression indeed a culmination of a universal tendency towards perfection: the microcosm that measured the macrocosm. Nature-philosophy was very much associated with the thought of the great German savant Goethe, and survives today in its purest form in anthroposophy the view of life developed by the Austrian philosopher Rudolph Steiner. It also turns up, more or less disguised, in various alternative points of view, from homeopathy to ecological activism. Given this heritage, many scientists would be intrigued, even horrified, to learn (if they did not already know) that modern developmental biology grew directly from the work of nineteenth-century German embryologists who had been schooled in the prevailing atmosphere of nature-philosophy. Indeed, after long dormancy, it is now almost possible for a serious biologist to whisper the name of Goethe in a lecture without raising sniggers at the back.

Next page