Table of Contents

I think were property.

I should say we belong to something:

That once upon a time, this earth was No-mans Land,

that other worlds explored and colonized here,

and fought among themselves for possession,

but that now its owned by something:

That something owns this earth all others warned off.

...

I suspect... that all of this has been known, perhaps for ages,

to certain ones upon this earth, a cult or order,

members of which function like bellwethers to the rest of us,

or as superior slaves or overseers, directing us in accordance

with instructions received from Somewhere else

in our mysterious usefulness.

Charles Fort, The Book of the Damned , 1919, p. 163

Above all, to

SCOTT DOUGLAS de HART:

A true master, adept, and poet of deep mysteries,

who crossed the Rubicon with me:

Anything I could say, any gratitude I could express,

are simply inadequate for you;

You are a true

And to

TRACY S. FISHER:

You are, and will always be, sorely missed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Every book such as this one is the product of that intricate calculus of human interaction. It is the offspring of conversations between close friends with common interests and outlooks, of conversations with books written long ago by authors long forgotten, who yet in the immediacy of the media of information are ever present to us.

This book is no different. The authors from long ago and more recent times are encountered in its main text, but the conversations had with friends who have in their own way contributed to many of the insights of this book are a different matter, and these people must be mentioned. George Ann Hughes and I have known each other for about three years through her Internet broadcast, The Byte Show. What began as a professional relationship has morphed into a friendship where the free flow of ideas is always paramount, and many of her insights are recorded herein. Thank you, George Ann.

The same, likewise, must be said for my friend Richard C. Hoagland, who also over many emails and phone calls these past two years has made his own observations and contributions to this book, particularly in how space anomalies fit into the larger picture. I hope I have done some justice to his thoughts here. Thank you, Richard.

Above all there has been one friend, Dr. Scott D. deHart, whose constancy as a friend in some of the darkest periods of my life has been unwavering, and whose conversations over this last third of my life that I have had the honor and privilege of knowing him, have so mightily contributed to the ideas presented herein that in truth, he is a co-author and equal contributor to it. Many of the ideas, particularly in the last two parts of the book, are reflective of conversations weve had over the past decade. For him and for these conversations and his friendship, and in many cases mentorship, no words of gratitude suffice, but nonetheless I say it anyway: thank you, Scott.

Joseph P. Farrell

Spearfish, South Dakota

2010

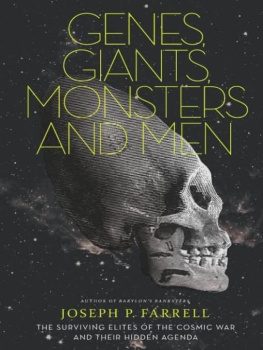

Introduction

HOW DOES ONE MAKE SENSE of ancient texts, modern genetics, legends of monsters and giants, fossils, the origins of man, and the attempts of some religions, to obscure all of it? How does one synthesize it all? Is it even possible to speak in one breath of giants, monsters, ancient texts and evolution?

Asking these questions highlights the problem, and the problem is the texts, what we mean by them, and what we think they mean.

Pretty much everyone with half a brain, and who has not been lobotomized by the American education system or subjected to the psychedelic drugs and mind-numbing electroshock of its dull university curricula, even duller professors, and to its textbooks that contain no primary texts, is agreed that something is wrong with our standard model of history, particularly the farther back one goes. Only a university academic, for example, could believe that humanity was around for about 150,000 years (if one is to believe the geneticists), and doing nothing but hunting and gathering, and then all of a sudden, and for no explicable reason, decided to invent civilizations such as Sumer (and all its Mesopotamian offshoots) and Egypt out of whole cloth, undertake monumental ziggurat or pyramid construction, invent calendars, agriculture, wheels, writing, mathematics, music, astronomy, banking, and maybe even electricity, as evidenced by the Baghdad Battery.

Consequently, when it comes right down to it, we have a choice between fairy tales, or, if one prefers, between mythologies or dogmas.

We can believe the hypnotic incantations of biology, history, and anthropology professors waving their wands, and producing cute animated videos of the primordial soup gradually evolving into complex organic life (fish), whose fins gradually morph into limbs as they crawl out of the soup onto the sand (reptiles) and, as the computer-generated animation proceeds, gradually morphing into a veritable cornucopia of evolutionary progress over billions of years (insert Carl Sagan voice here).

Or we can begin to take seriously what those ancient societies that suddenly sprang up out of whole cloth and almost ex nihilo said happened. There the picture is equally disconcerting, for one is almost immediately confronted by wild tales of giants, monsters, men and even if one reads the texts a certain way with genetic manipulation and extraterrestrials, and a cast of characters that range the whole spectrum from nobility to a genocidal disposition and behavior that would make a Stalin or a Hitler seem like paragons of virtue, restraint, and compassion.

Indeed, the comparison with Stalin and Hitler is an apt one, for if one reads certain ancient texts from Sumeria or India, one encounters over and over such characters, whether gods or men, engaged in a titanic struggle for power that ultimately resulted in a cosmic war, and its aftermath. Yet, if one is to believe the ancient stories, the monsters and giants and manipulations remained after that war was over, scattering themselves along with some of the technology by which it was fought, yet doing so with no consistency. For example, one finds both the Sumerian Anunnaki and the Hebrew Nephilim siring chimerical and gigantic offspring with human women, and yet the context in which the story is told Sumerian polytheism versus Hebrew monotheism changes drastically, and implies a hidden agenda (or agendas) behind each version of the story.

This book looks at things from the standpoint of the second fairy tale; that is, it assumes that a very ancient cosmic war was fought within our own solar system, by a civilization with interplanetary extent, and which was based on this planet, the Moon, Mars, and various satellites of the gas giants. As I have detailed elsewhere, that war was so destructive that the civilization waging it was nearly wiped out, leaving its surviving elites to pick up the pieces as best as they could, and begin the long, slow climb back up to a similar pitch of scientific and technological development. The course of that war, and its aftermath, was populated by a bizarre pantheon of gods, of giants the chimerical offspring of the gods and man and by even more chimerical monsters, and of course, by humans. These, and the deeper implied issues of a sophisticated genetic science in existence in very ancient times, constitute the obvious motifs of this book. They are the portals by which we will enter into the central theme of this book, which is to acquire a preliminary understanding of the agendas of those elites that survived the cosmic war and catastrophe, and to trace a broad chronology of their activities.