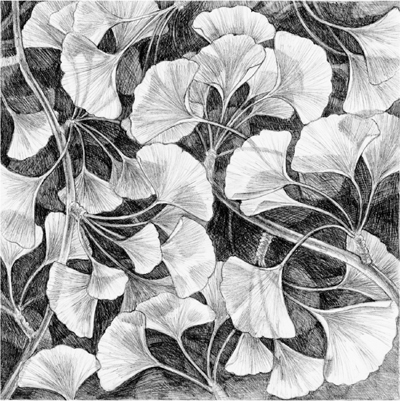

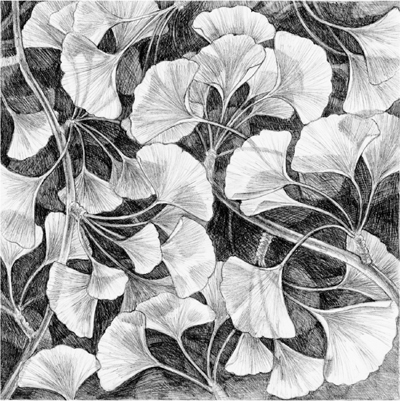

Ginkgo

Ginkgo

THE TREE THAT TIME FORGOT

Peter Crane

WITH A FOREWORD BY PETER RAVEN

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2013 by Peter Crane. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Minion type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Crane, Peter R.

Ginkgo : the tree that time forgot / Peter Crane.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18751-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Ginkgo. I. Title.

QK494.5.G48C73 2013

585.7dc23 2012032831

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOR EMILY AND SAM

with hope for their generations wider view of the world

Ginkgo biloba

Dieses Baums Blatt, der von Osten

Meinem Garten anvertraut,

Giebt geheimen Sinn zu kosten,

Wies den Wissenden erbaut.

Ist es ein lebendig Wesen?

Das sich in sich selbst getrennt;

Sind es zwey? die sich erlesen,

Dass man sie als eines kennt.

Solche Frage zu erwiedern

Fand ich wohl den rechten Sinn;

Fhlst du nicht an meinen Liedern,

Dass ich Eins und doppelt bin?

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, September 15, 1815

Ginkgo biloba

This trees leaf which from the Orient

Is entrusted to my garden

Lets us savor a secret meaning

As to how it edifies the learned man.

Is it one living being?

That divides itself into itself

Are there two who have chosen each other,

So that they are known as one?

To reply to such a question

I found, I think, the condign sense.

Do you not feel that in my poems

I am single and twofold?

English translation by Kenneth Northcott, 2006

Contents

Foreword

Perhaps the best known and most easily recognized of the worlds 100,000 kinds of trees, ginkgo stands out by virtue of its unique features, amazing history, and long association with people. With their distinctive fan-shaped leaves and tall trunks, ginkgo trees adorn parks, streets, and recreational areas throughout the temperate regions of the world. When the weather turns sharp, all of the leaves suddenly turn a brilliant yellow, dropping soon after to lay a lovely, bright yellow carpet under each tree. Ginkgo trees are bisexual, some producing seeds and others only pollen-bearing organs. The seeds are naked, as in other gymnosperms (such as pines, cycads, and cedars); the fleshy outer coat of the ginkgo seed smells strongly of rancid butter (butyric acid). The inner kernel of the seed is nutlike and eaten widely in the Orient, once the smelly outer layer and the stony inner one are removed. Among the seed plants, only ginkgo and cycads form motile sperm within their pollen tubes, a fascinating example of the survival of an archaic characteristic.

A particularly fascinating feature of ginkgos history is that it is extremely rare as an uncultivated native tree. Once widespread throughout the Northern Hemisphere, it disappeared at different times in different regions, including most of Eurasia and all of North America, as the climate changed and new plant communities came into being. In the Northern Hemisphere, China represents the zone where the most ancient lineages have survived, including many that were once widespread. Only in two moun tainous areas of southern China do the varied genetic patterns of the standing trees make it likely that they or their immediate ancestors were native to the forests where they still occur. In addition, however, individual trees here and there in southern China may represent originally wild individuals that survived and eventually were protected by the people who lived near them, as is the case in the dawn redwood, Metasequoia. That ginkgo has survived essentially unchanged for as much as 200 million years is a miracle: virtually all other kinds of plants and animals that occurred with it more than 150 million years ago have become extinct. Those that disappeared included the relatives of the surviving evolutionary lineage to which Ginkgo biloba belongs. Although defining species from fossil material alone is difficult, ginkgo may legitimately be regarded as the oldest surviving kind of plant: the characteristics of the living species closely resemble those of its Jurassic ancestors!

Starting about a thousand years ago, ginkgo was brought in from the wild, or simply allowed to survive where native, in the temple gardens and protected forests of China; it has been nurtured and valued by human beings over the past thousand years or more. Ginkgo evidently was spread from there to Korea and Japan over the course of the past 800 years or so. After Europeans discovered it in Japan in the late seventeenth century, it was brought into cultivation in Europe over the next several decades, eventually spreading around the world in areas with a suitable climate. Ginkgo is resistant to air pollution and to pests and diseases, doing very well as a city tree through temperate zones of both Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Without the attention of human society, ginkgo would doubtless have become extinct by now, or at best reduced to a few individuals. In that sense, its history affords an excellent example of how we must deal with many plant species in this age of change and extinction if we wish to save them for the future.

As Peter Crane has emphasized in the closing pages of this fine book, human beings have had a short span of existence on this 4.5 billionyearold planet, and we live only a short time as individuals. That we share the Earth with such a venerable organism, with a history where hundreds and tens of millions of years are relevant, should help to give us a better perspective from which to think of our own lives and existence here and thus prepare as well as we are able for the future. Our short-term actions are ruining the world in which we live much faster than we can imagine, with the worlds sustainable capacity sufficient to provide less than two-thirds of what we consume each year, even though billions of us live hungry and in extreme poverty. The two billion or more additional people who will join our numbers in the next several decades will almost all be poor, entering a world that we, with our largely short-term view of progress, are destroying rapidly. Might not we be able to learn from the deep past and then redouble our efforts to sustainably use our planets resources and thus live within its productive capacity while we still have time to do so?

Next page