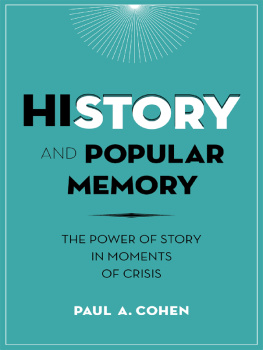

HI STORY

AND POPULAR

MEMORY

HI STORY

AND POPULAR

MEMORY

THE POWER OF STORY IN MOMENTS OF CRISIS

PAUL A. COHEN

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

EISBN 978-0-231-53729-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cohen, Paul A.

History and popular memory : the power of story in moments of crisis / Paul A. Cohen.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16636-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53729-2 (e-book)

1. HistoriographySocial aspectsCase studies. 2. Collective memoryCase studies. 3. CrisesHistoryCase studies. 4. Kosovo, Battle of, Kosovo, 1389Influence. 5. Masada Site (Israel)Siege, 7273Influence. 6. Goujian,465 B.C.Influence. 7. Joan, of Arc, Saint, 14121431Influence. 8. Aleksandr Nevskii (Motion picture)Influence. 9. Henry V (Motion picture : 1944)Influence. I. Title.

D13. C589 2014

907.2dc23

2013032842

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

FOR JESSE, JULIA, AND TALYA

CONTENTS

MAPS

FIGURES

I n a recent book, Speaking to History: The Story of King Goujian in Twentieth-Century China, I examined in some detail the power that an ancient Chinese story had at a number of key junctures in the history of China in the twentieth century. During that span of time, the storys impact was greatest at moments of protracted crisis, such as the mounting tension with Japan in the years leading up to the Sino-Japanese War of 19371945 and the predicament of Chiang Kai-sheks beleaguered Nationalists on Taiwan after 1949. By presenting a model of the world that incorporated a favorable outcome for the crisis, the right story in these circumstances pointed to a more hopeful future. What especially intrigued me about this process was the resonance or reverberation between story and situation, between a narrative and a contemporary historical condition that prompted those living in it to attach special meaning to that narrative.

Apart from the resonance between Moses/Joshua and King/Obama, there was an additional layer of meaning in the biblical story because although Moses himself didnt make it to the Promised Land, he was instrumental in freeing the Jews from bondage in Egypt and thus served as a powerful metaphor for the eventual realization of African American liberationa dream that in American history Martin Luther King Jr. articulated and Barack Obama finally exemplified.

There are many other human communities as well in which stories of a religious character have taken an important part in the lived experience of the communitys members, often serving as a template for this experience. But equally common are instances in which communities have looked for such sustenance to narratives from their own pasts, stories that, although undergoing a greater or lesser degree of reworking over time, had real historical origins. This process has perhaps been unusually prevalent in China, where since time immemorial people have demonstrated a strong affinity for stories dressed in historical garb, but the part taken by such storieswe might call them history stories as opposed to stories grounded in religion or mythhas been compellingly demonstrated in many other societies also.

In the process of writing the Goujian book, I became sensitized to the overall pattern of how the interplay between past story and present history functioned, and so I thought it might be interesting to see what happened if, from the multitude of possible examples, I selected a finite number, all relating to a specific set of issues, and looked at them in some depth. In this book, I focus on six countriesSerbia, Palestine/Israel, China, France, the Soviet Union, and Great Britainall of which faced severe crises in the course of the twentieth century. The crises I have singled out to deal with in every instance involved war or the threat of war, in response to which the populations and states affected drew upon older historical narratives that embodied themes broadly analogous to what was taking place in the historical present. Creative worksplays, poems, films, operas, and the likeoften played an important role in the recovery and revitalization of these narratives, and as we would expect in the twentieth century, nationalism took a vital part in each case.

This reverberation between story and history is a phenomenon of no little historical interest. It is, however, exceedingly complex, reflecting deeply on how individual leaders or entire peoples or subgroups within a society position themselves in the space of historical memory. The manner of this positioning varies significantly from instance to instance. Yet running through them all is a constant: the mysterious power that people in the present draw from stories that sometimes derive from remotest antiquity and that, more often than not, recount events that, although making claims to historical accuracy, have been substantially reworked over time and have only the thinnest basis in an actual historical past. The question the eminent psychologist Jerome Bruner poses in reference to this storytelling phenomenon, although not referring explicitly to history, is central. Why, he asks, do we use story as the form for telling about what happens in life and in our own lives? Why not images, or lists of dates and places and the names and qualities of our friends and enemies? Why this seemingly innate addiction to story?

The power of story, so common and yet so poorly understood, merits far more scrutiny than it has generally received from historians. My hope is that the multifaceted connections developed in this book between story and history in a range of cultural settings and historical circumstances may serve to illuminate the problem he raises.

Because the older stories never supplied an exact match to what was currently transpiring in history, they were regularly modified to a greater or lesser degree to make the fit closer. This is where popular memory became important. Popular memorywhat people in general believe took place in the pastis often a quite different animal from what serious historians, after carefully sifting through the available evidence, judge to have actually taken place. This distinction between memory and history, vitally important to historians, is often blurred in the minds of ordinary folks (that is, nonhistorians), who are likely to be more emotionally drawn to a past that fits their preconceptionsa past they feel comfortable and identify withthan to a past that is true in some more objective sense. This blurring is of course greatly facilitated when, as a result of a dearth of historical evidence or the unreliability of such evidence as has survived, even professional historians cannot know with absolute confidence what occurred in the past. Such is the case with each of the examples dealt with in the following pages. But, as we shall see again and again, even when there exists a minimum core of certainty about what happened in the pastthat Joan of Arc, for instance, was burned at the stake in 1431 or that the forces of the Roman Empire besieged Jerusalem and destroyed the Second Temple of the Jews in 70 C.E.the power of the historians truth often has a difficult time competing with the power of the right story, even though (or perhaps precisely because) the latter has been hopelessly adulterated with myth and legend. A major objective of the present book is to seek a deeper understanding of why this is so.