CONTENTS

Bhagavad Gita

Bhagavad Gita

A New Verse Translation by Stanley Lombardo

Introduction and Afterword by Richard H. Davis

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2019 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

19 1

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244 - 0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Brian Rak and Elizabeth L. Wilson

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lombardo, Stanley, 1943 translator. | Davis, Richard H., 1951 author of introduction, author of afterword.

Title: Bhagavad Gita / translated by Stanley Lombardo ; introduction and afterword by Richard H. Davis.

Other titles: Bhagavadgita. English.

Description: Indianapolis, Indiana : Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., [ 2019 ] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | In English, translated from Sanskrit.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042396 | ISBN 9781624667893 (cloth) | ISBN 9781624667886 (paper)

Classification: LCC BL 1138.62 .E 5 2019 | DDC 294.5 / 92404521 dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042396

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-799-2

The Arthastra: Selections from the Classic Indian Work on Statecraft . Edited and Translated, with an Introduction, by Patrick Olivelle and Mark McClish.

The Nyya-stra . Translated, with Introduction and Explanatory Notes, by Matthew Dasti and Stephen Phillips.

{v} CONTENTS

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

{vii}

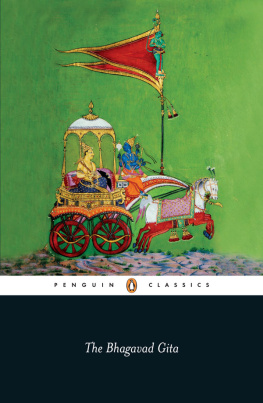

The Bhagavad Gita opens with one of the most compelling scenes in Indian, or world, literature. Two enormous armies have been drawn up opposite one another on the expansive plain of Kurukshetra, the field of the Kurus, in northwest India. Both are vast and fearsome and both seem impossible to withstand. Teeming with elephants, chariots, and horses, they resemble two opposing forest ranges. One side is allied with the five Pandava brothers, the other with their cousins, the one hundred Kaurava brothers. The great elderly warrior Bhishma, surrogate grandfather to both sides, lets out a resounding battle cry like a roar of a lion and blows his conch shell. Leading warriors on both sides answer his call with their own blasts on conches. Throughout the two armies the tumult of cymbals, kettledrums, horns, and conches rises to a crescendo, reverberating fearfully across the sky and earth. And into the no-mans-land between the two armies ventures one chariot. The most potent warrior on the Pandava side, Arjuna, has asked his charioteer Krishna to drive him there so he can survey the two opposing forces.

When the warrior and charioteer arrive there, however, Arjunas zeal for the coming battle begins to wane. He is overcome by pity, and he feels like he is falling apart. As he reports to Krishna,

Seeing my own people, Krishna,

drawing near in battle frenzy,

Both my legs collapse beneath me,

my mouth is dry, my tongue is cracked,

all my body shakes and trembles,

my hair bristles and stands on end.

My bow Gandiva falls from my hand,

and my skin feels like its burning.

I cannot stand in position,

and my mind is wandering off. ( 1.28 )

{viii} Arjuna explains that he can see no good that could possibly result from the coming war. He views it as a terrible sin. Finally, with his heart overwhelmed by grief, Arjuna sits down in the rear of the chariot and drops his bows and arrows.

This is surprising indeed. Throughout his life Arjuna has been the most fervent and accomplished of warriors. As a member of the ruling Kshatriya class, he has been trained by the best teachers available in the arts of war. In contests among his peers he has consistently prevailed. Moreover, in preparation for this long-anticipated battle with the Kauravas, Arjuna has undertaken a lengthy and arduous journey to collect weapons. He performed rigorous austerities in the Himalayas, wrestled with the god Shiva, and visited Indras heaven. Now he comes to the battlefield armed with an array of weapons of truly mass destruction, including the fearsome Pashupata weapon that is capable of burning up the entire world. No one would expect Arjuna, of all warriors, to suffer from battle fright.

But it may not be so surprising after all. Battle may be the mtier of a Kshatriya male like Arjuna, but war also represents a failure. In this case, the vast hordes of warriors have gathered at Kurukshetra because one family has failed to resolve its own differences. The Bhagavad Gita is a portion of a much longer epic poem, the Mahabharata , which tells in detail how the Kshatriya lineage descending from the great king Bharata has fallen into deep and irreconcilable conflict. The closely related Pandava and Kaurava brothers are at each others throats over a throne. When Arjuna speaks of my own people, he refers to his own first cousins, the Kauravas, as well as other close relatives. Arjuna recognizes this internecine hostility to be evil.

Do we not know enough, Krishna,

to turn aside from such evil?

To understand how wrong it is

to destroy friends and family?

With destruction of the family

ancient family customs vanish,

and lawlessness overpowers

the entire family structure...

Men whose family laws are wiped out

dwell in hell indefinitely.

{ix} Have we not heard this repeated,

again and again, Lord Krishna? ( 1.39 , )

Destroying the family, corrupting society, creating chaos, dwelling in hellto Arjuna the stakes appear high indeed.

Krishnas first response to Arjunas trauma, naturally enough, is astonishment and scorn.

Why has this craven timidity

appeared at this critical hour?

It is ignoble, Arjuna,

and closes the gates of heaven.

Son of Pritha, do not give in.

This cowardice is beneath you!

Shake off this vile faint-heartedness

and rise up, O Scourge of the Foe! ( 2.2 )

Sounding like the coach of a football team trailing at halftime, Krishna berates Arjunas lack of resolve and rallies him to action. In the culture of the Kshatriya class, with its ethos of honor and heroic manliness, Krishnas allusion to emasculation ( klaibyam , impotence) is a particularly low blow. However, Arjuna does not give in to Krishnas scolding, not right away, for his qualms about this war are much more profound. And it is thanks to the depth of Arjunas concerns that we have the seven hundred verses that constitute the dialogue of Arjuna and Krishna that make up the Bhagavad Gita . All action is suspended as warrior and charioteer begin a discussion that moves from battle anxiety to ethics, theology, and a vision of God. Krishna pulls out all the stops in his effort to overcome Arjunas doubts and to persuade him to fight.

Teachings on the Field of Battle

Krishna shifts quickly from his first attempt to shame Arjuna. Faced with a fearsome battle of uncertain moral status, Arjuna will require stronger reasons to fight. Krishna begins to develop a more compelling and persuasive argument. To do so, Krishna draws on many ideas and practices that would {x} have been familiar to a well-educated member of the ruling class in classical India, as Arjuna was. He also introduces several new and truly innovative concepts, and synthesizes them all into his compelling case. It is not possible to summarize Krishnas full presentation here, but it is worth following the conversation to highlight some of the key ways Krishna addresses Arjunas deep reluctance on the field of Kurukshetra.