I LLUSTRATIONS

Figures

Maps

Introduction

And call by his own name his people Romans.

For these I set no limits, world or time,

but make the gift of empire without end.

Virgil, The Aeneid

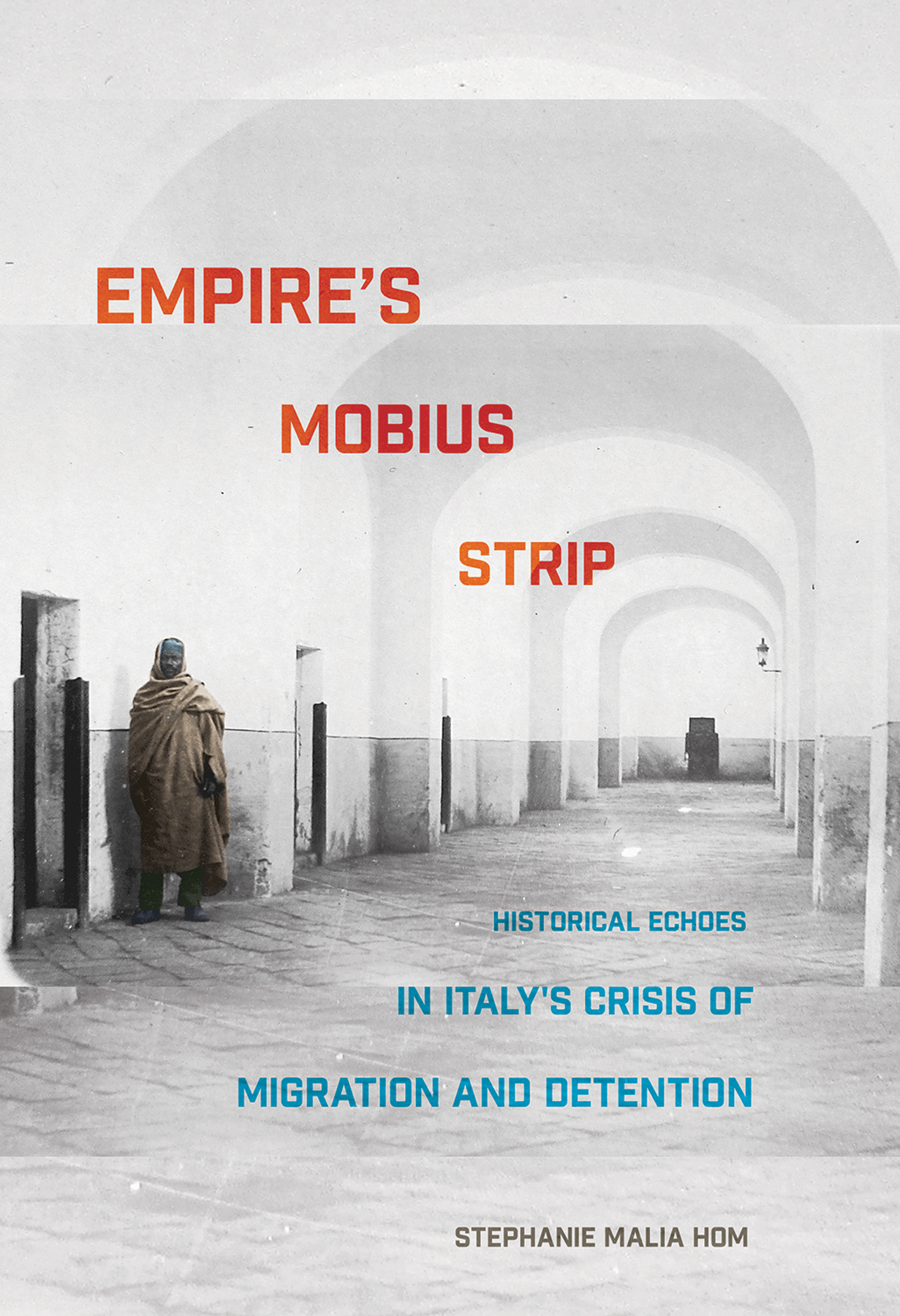

Italian empire, by conventional definition, was a short-lived affair. It lasted just eight years, bookended by Italys invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and the fall of the Fascist regime in 1943. Its relative brevity has led, in part, to its omission from studies of modern European imperialisms even though Italys colonial projects in East Africa and Libya stood among the most brutal and bloody of the last century.

Empire was anything but short-lived for the hundreds of thousands of Italians who carried out Italys imperial ambitions. Nor was it brief for the many more people who became subjects of those ambitions and have since remained subjugated to that power decades after Italian empire officially ended. Empire creates a ripple effect across time and space, and in the words of Ann Stoler, saturates the subsoil of peoples lives and persists, sometimes subjacently, over a longer dure. These are uneasy, messy constellations always in the process of becoming and unraveling.

Some imperial formations are more explicit than others. In the context of modern Italy, take, for example, the Via dei Fori Imperiali in Rome (). Built between 1924 and 1932, this street physically and symbolically linked the foremost sign of Italys ancient empire, the Roman Colosseum, with the nerve center of its new Fascist empire, Piazza Venezia. Mussolini ordered the demolition of one of Romes most densely populated neighborhoods to make way for this imperial artery, evicting and displacing thousands of residents, appropriating their homes, bulldozing churches, razing gardens, demolishing medieval and Renaissance structures, and destroying untold numbers of archaeological ruins, the debris of the Roman Empire. The road still stands, and each day thousands of tourists shamble along this vector of Italys empires, appropriating the space anew.

IGURE View of the Via dei Fori Imperiali and Colosseum, Rome. Photograph courtesy of Shutterstock, 2017.

The Via dei Fori Imperiali is a clear example of an imperial formation materialized in brick and cobblestone. Concretized in roadwork and by rhetoric, Italys new Fascist empire symbolically and physically appropriated the empire of ancient Rome along the Via dei Fori Imperiali.

Other imperial formations are harder to pinpoint. Sometimes they require adjusting ones critical lens to recognize deeper, subtler constellations that arise over time. For example, take the controversial nomad emergency decree issued in 2008 by then prime minister Silvio Berlusconis government. This decree pronounced nomads a threat to public order and security, by which it meant the Roma specifically (who are pejoratively called gypsies). Some of these Roma were Italian citizens. Others had migrated from European Union (EU) countries and had the legal right to reside in Italy. Still others came from elsewhere such as the Balkans.

By declaring a state of nomad emergency, the decree empowered municipalities including Rome, Naples, and Milan to intervene with force. Bulldozers and excavators arrived with little notice at the entrances of Romani settlements known as campi nomadi (nomad camps) and quickly went to work demolishing them. When the bulldozers were finished, all that remained of these communities were crumpled walls and scattered two-by-fours. Thousands of Roma were dispossessed and displaced in the process. This act of forced dislocation has a name in Italian: sgombero. It is roughly translated as eviction but carries connotations of evacuation, clearing, vacating, and loss as well. The Roma who lost their homes by sgombero either relocated to other camps or became sequestered in government-built villages scattered along the urban periphery.

Yet the Roma were not the first nomads who presented a threat to the Italian state. Italian colonial officials considered il grande nomadismo (the great nomadism) of Bedouin tribes in Libya a clear and present danger, so much so they declared a state of emergency against them in 1930. This nomad emergency decree paved the way for the forced dispossession and displacement of more than one hundred thousand Bedouin from their homelands. Not only that, the decree also provided the juridical pretense for imprisoning them in Italian-built concentration camps along the desolate Cyrenaican coast. Nomadism was thought to be so threatening that it could be countered only by immobilization. The squalid conditions of these camps made for deathly living among the barbed wire, frayed tents, famine, intractable diseases, and endless dust and wind. In the span of just five years, 192933, at least forty thousand Libyan Bedouins died in these Italian-built concentration camps. Some historians put the death toll closer to seventy thousand. It was a genocide that remains little known outside Libya today. If mentioned at all, the camps are but footnotes in studies of European imperialisms. More often than not, they are simply absent, unknown, and long repressed by the myth of Italians as good colonizers.

When we expand our analytic frame, the bonds between what were once seen as distinct constellations are revealed. In this example, the nomad emergencies that manifested almost a century apart are connected by the practices and the logics rooted in Italys imperial ambitions. The one finds direct resonance in the other. Practically, Italian functionaries took the same actions to neutralize the threat of nomadism: they dispossessed, dislocated, and immobilized Bedouin and Roma in concentration camps and government-built villages, respectively. Logically, what links the Roma of today with the Bedouin of yesterday was the threat their nomadism allegedly posed to Italian sovereignty. It was deemed an utmost danger to public safety under the auspices of which racist and xenophobic violenceeven genocidecould be carried out in the name of the state. Suffice it to say, the nomad emergencies declared in Italy and Libya almost a century apart signal the surfacing of an imperial formation in all of its messy, uneasy, violent becoming and unraveling. The camps and villages linked to nomadism are hardly imperial debris but rather live sites of this formation as it stretches out across time and folds back on itself: empires Mobius strip.

This study examines, historically and anthropologically, the imperial formations that have shaped modern Italy. It traces the ways in which Italys neglected colonial history, particularly in Libya, has been cited and expanded in its current crisis of migration and detention. To be more precise, Italys disavowed colonial past not only becomes expressed by this crisis but also emerges with amplified force. I take up the task set forth by anthropologists and historians of empire who have called for a reimagining of how imperial formations organize contemporary practices structured in dominance as well as how they demarcate and particularize histories of the present. My study grapples with the messy ways that Italys empire organizes itself across time and space, and how that organization violently produces exclusionary spaces and marginalized subjects, and, at the same time, generates the very structural conditions for inclusion within the Italian state and related civic projects.