Wood - Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present

Here you can read online Wood - Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: La Vergne, year: 2017, publisher: Perseus Books, LLC;BlueBridge, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2017 by Frances Wood

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Published by

Blue Bridge

An imprint of

United Tribes Media Inc.

Katonah, New York

www.bluebridgebooks.com

ISBN: 9781629190167

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016959624

Cover design by Cynthia Dunne

Cover art: Studying scholars in a garden (Hanging scroll).

From a private collection. Photo Credit: HIP / Art Resource, NY

Text design by Cynthia Dunne

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Table of Contents

T he earliest significant body of Chinese writing is to be found on the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty (c. 16001046 BCE). These texts are records of divinations, questions concerning the outcome of such activities as military and hunting expeditions and childbirth; they are not literary but documentary and archival. The shoulder blades of oxen and turtle shells were used for divination by the Shang kings, whose territory centered on the eastern reaches of the Yellow River valley down to the Yangtse. The texts inscribed on the oracle bones were short and to the point, but the characters used were the ancestors of todays Chinese script, made more intelligible to us through the Shuo wen jiezi dictionary (analysis and explanation of characters) of 121 CE. Traditional Chinese historiography traces a line of rulers through from the Shang to the Zhou kings, who came from west of the Shang territories and conquered the Shang in 1046 BCE. Recent archaeological discoveries, at Sanxingdui in Sichuan province, for example, have enriched the picture, demonstrating that there were other, and different, local civilizations flourishing in west and south China at the time, though not recorded in the traditional histories. It is from the Zhou that the first body of literature emerges (including the classics associated with Confucius and the Daoist classics), although the passage of millennia means that surviving texts may have considerably changed from their original state.

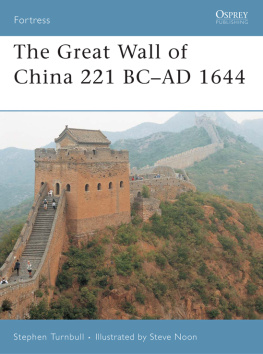

Zhou rule, which instituted a system of fiefdoms, collapsed in the fifth century BCE when its territorial control broke down into several distinct warring states. Then, after hundreds of years of fighting, a vast areafrom north of Beijing to near Guangzhou in the south, and from the eastern seaboard to the western area of todays Sichuan provincewas united by the ruler of the state of Qin in 221 BCE. The ruler of Qin proclaimed himself emperor (thus he is known as the First Emperor) and moved away from the aristocratic system of rule by fief, replacing it with the beginnings of the bureaucracy, a government staffed by trained officials armed with books containing the legal code and administrative regulations. Though the paramount importance of legal training weakened after the fall of the Qin in 206 BCE, the principle of bureaucratic rule was to continue until the early twentieth century.

The First Emperor unified the state that we now know as China by enforcing several methods of standardization, erasing the differences of the separate warring states by imposing a national standard of weights and measures, coinage and writing system. The form of coinage instituted lasted until the early twentieth century, but the standardization of the script was possibly the most significant element underlying the continuity of Chinese civilization and culture. Over the vast territory of China, then as now, many different dialects (or local languages) are spoken, but the written language is generally common to all, even if the characters might be pronounced differently in different areas. The Chinese script does not represent the sounds of the language today, as it is not a phonetic script but a series of up to 44,000 (the number included in the great Kangxi Dictionary [Kangxi zidian] of 1716) different characters. Though many non-sinologists still like to describe them as pictograms, very few of todays characters are simple pictures of things: most are much more complex, made up of phonetic elements, phonetic loans, and combinations of these, now frequently combined so that many words consist of two syllables or two characters.

The Qin dynasty, though hugely significant, was short-lived, barely outlasting its founding emperor. It was overthrown by the Han. The Han dynasty (206 BCE220 CE) continued and further developed the bureaucratic system of government and largely maintained the same system of law and punishment that it deplored in the Qin. Han historical writing pioneered the line of moral justification by which each new dynasty wrote the history of the previous regime that it had overthrown. In order to justify this violent act and demonstrate the righteous assumption of the Mandate of Heaven, it was necessary to vilify the preceding dynasty, thus the Han histories condemned everything about the Qin. It was during the Han that the precepts associated with Confucius (c. 551c. 479 BCE) began to be associated with the concepts of moral rule and family worship.

The earliest extant texts (aside from the oracle bone inscriptions, which are divinations rather than literary texts) are those written on strips (or slips) of bamboo or wood during the Warring States period (475221 BCE). These rare survivals include the earliest versions we have of the Confucian classics and Daoist classics.

The collapse of the Han dynasty in 220 CE was followed by over three centuries of disunion, with various small states and ruling houses competing and fighting for power: the eras of the Three Kingdoms and the Western Jin, followed by the Sixteen Kingdoms in the north and the Eastern Jin in the south, and then the Northern and Southern dynasties. At last the Sui dynasty reestablished central control in 581 CE. But the Sui rule did not last long and was overthrown in 618 CE when the Tang dynasty (618907 CE) was established. The Tang is often regarded as a golden age: the capital city, Changan (todays Xian, in Shaanxi province), was the greatest in the world, boasting a rich and multicultural population, with merchants from all over Central Asia bringing luxury goods to the city and building mosques and Nestorian and Manichaean houses of worship alongside the Buddhist and Daoist establishments already there. A great age of poetry, many descriptions survive of the wealth, luxury, and splendor of the court (its furnishings and entertainments) and the contemporary fascination with Central Asian fashions in clothing, music, and dance.

Tang dynasty wall paintings from Buddhist cave complexes such as that near Dunhuang (Gansu province) reveal some of the earliest extant depictions of landscape, a subject that was to dominate Chinese painting for the next millennium. Paintings on paper and silk survive only through later copies that may not wholly reflect the appearance and style of the original. As with painting, an art to be learned and developed through constant copying of masterpieces, the art of poetrydeveloped to a high point during the Tangoften rested on the delicate and subtle interpretation of well-known themes and subjects, with frequent references to masters of the past.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present»

Look at similar books to Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Great Books of China From Ancient Times to the Present and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.