A heartfelt, witty prescription for a life worth aspiring to and genuinely well-written. Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall on A Pike in the Basement

A banquet of good stories. Elizabeth Luard on A Pike in the Basement

Not just one of the best books on wine, its one of the best books on France. Michael Palin on Puligny Montrachet

Enthralling Puligny comes alive through Mr Loftus. The New York Times on Puligny Montrachet

This has been a long project, testing the patience of family and friends. To all of them, and especially to my beloved wife Irne, my heartfelt thanks.

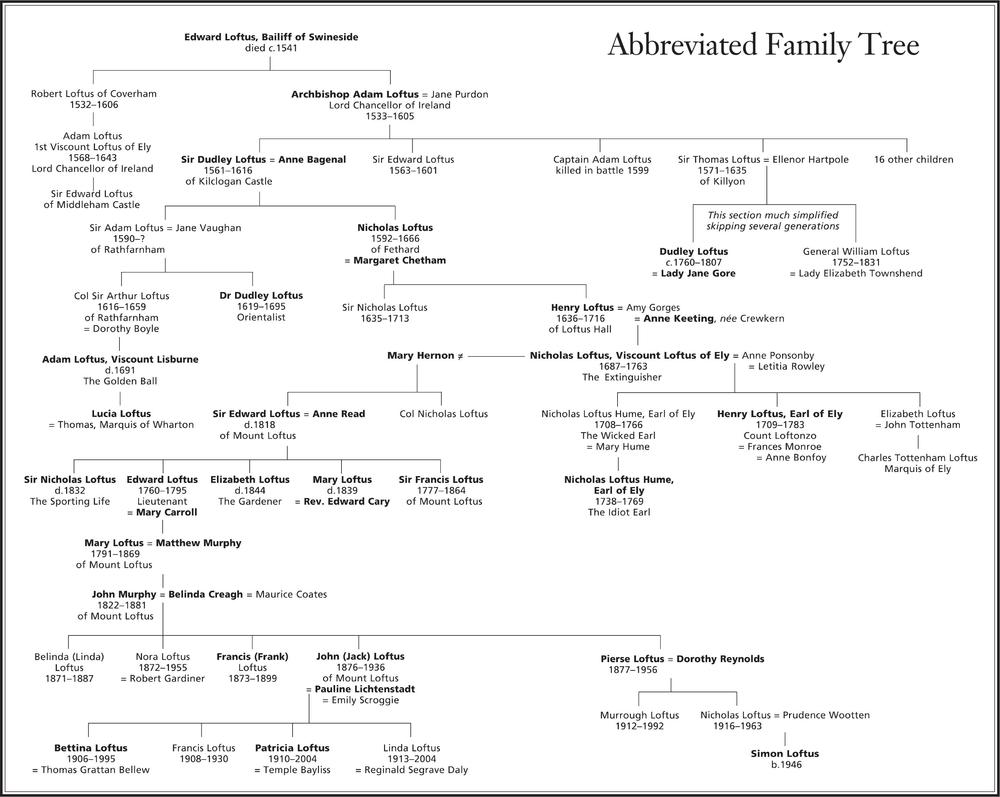

My siblings Belinda and Michael Loftus, my cousins Idrone Brittain and Jack Bayliss, and my friends Hugh Brody, Jeremy Isaacs and Dan Franklin took the trouble to read and comment on the text, in earlier, baggier drafts. Each made vital suggestions, including ruthless pruning, which have improved the end result. My email correspondence with a distant cousin, Guy Loftus, became almost as long as the book itself. Guy read every chapter, supplied a mass of information, references and useful comments, compiled by far the most complete version of the Loftus family tree (www.loftusweb.com/tree.htm) and has been a wonderfully supportive critic, over many years. Thanks also to Liz Calder, Carla Carlisle and Juliette Mitchell. Among the scholars who commented on particular sections I am grateful to Elizabeth Boran, Peter Boyle, Kerry Bristol, Billy Colfer, Ruth Connolly, Robin Darwall-Smith, Jane Dawson, Anthony Malcomson, Helga Robinson-Hammerstein and Clodagh Tait.

Librarians and specialists attached to various institutions helped me with cheerful generosity, notably Melissa Brennan (Rathfarnham Castle), Muriel McCarthy (Marshs Library, Dublin), Frances Egan (The Dublin Society), Katherine Jones (RIBA Library / Victoria & Albert Museum), Andrew Cormack (RAF Museum, Hendon), Alastair Lindsay (former architect at the Office of Public Works, Dublin) and the wonderful staff at the London Library.

Douglas Matthews made the index a task that he achieved with wit and clarity.

Thanks, above all, to James Daunt and Laura Macaulay of my publishers, Daunt Books. Their courage and support has amazed me, but should be no surprise to the many admirers of the wonderful business that James founded and continues to run.

S IMON L OFTUS

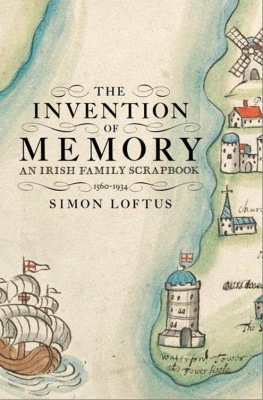

The Invention of Memory

This is a book about memory. It began with a collection of family stories, told me as a child; became an exploration of how things are remembered or forgotten, the gaps between experience and history; ended in a country graveyard, sitting on a tomb.

To start with, those stories. I inherited a crazy assortment of ancestral legends, featuring the highwayman Captain Freney, the racehorse Hollyhock, the Angelic Miss Phillips and a host of others, vivid as any characters of fiction. When I first visited the old family home in Ireland, at the age of seven, I was able to play with Freneys blunderbuss, marvel at Hollyhocks silver mounted hoof, gaze at a portrait of Miss Phillips. So it seemed they must be true, those wonderful tales.

Later, of course, I began to doubt. But I also became fascinated by the faces of my forebears, the sense of some strong continuing likeness in the family portraits. I wanted to know them. So I pored over documents, criss-crossed the Irish landscape and tried to feel my way into these forgotten lives by exploring their houses and using their possessions reading their books, grilling my toast on a wood fire with a seventeenth-century toasting fork, cocking a pair of flintlock pistols, shouting through a brass megaphone. All of these things embodied memory; all of them particular to a time, a place, a person.

I found a Receipt for a Person in Love, scrawled in a tattered account book. A terrifying scandal emerged from the bottom of a deed box exploding to life through the testimony of maidservants, tradesmen , wigmakers, doctors, assorted aristocrats and the victim himself. There were bills for wonderfully fine soles and a monstrous large turbot, and every necessity of life in a country house in Kilkenny at the beginning of the nineteenth century. And I discovered, to my amazement , that the most improbable stories were rooted in fact.

But I also began to realise how little of what looms large in the political history of the times survives in these ancestral memories. Looking through the eyes of my forebears is like viewing Irelands past in those distorting mirrors that you find at the end of the pier. Sometimes the proportions seem more or less familiar, but the witnesses are easily distracted. Sometimes we catch the merest glimpse of famous events from the corners of their glance.

That contrast between private and public memory is particularly acute in a country where all history rushes towards myth, where rival mythologies are expressed in brilliantly coloured fables, leaving little room for the maddening inattention of daily experience. This is a function of form. Irelands history, for many, is still a matter of oral tradition episodes are shaped for dramatic effect, in response to the speakers audience, as I know only too well. I was brought up in the belief that you should never let the facts get in the way of a good story. But the facts are stubbornly there sometimes buried deep or wrapped in layers of retellings, or in plain view but unnoticed. And the big, inescapable fact is the bitter history of Englands first colony.

For a hundred and fifty years after the arrival of Adam Loftus in Ireland, in 1560, the experience of colonial conquest dominates the family records. But the eighteenth century brings a change of mood, and the stories seem increasingly detached from the harsh confrontations of religious and national identity. A strange silence, fraught with ambiguities, even surrounds that defining moment, the rising of 1798, when Ireland came closest to shaking off the clasp of its colonial master. For a long time I was troubled by this, as I tried to weave together the private and the public histories of my family and of Ireland, and found the great themes slipping away; sometimes, it seems, deliberately ignored. But gradually it occurred to me that the passions and preoccupations of my ancestors, their daily concerns and childish enthusiasms, their eccentricities and achievements, might constitute an alternative narrative of Irish history inconsistent, privileged, partisan, riddled with gaps but no less real, in its way, than the eloquent myths of suffering Hibernia. Hence this family scrapbook.

Now, when I think about those family stories, they seem like memories of a wished-for world, inventing the past to absolve it but invention originally meant discovery, with the implied sense of something waiting to be found. I love the confusion between this archaeological meaning and its modern sense, of forging something new the ambiguity that runs through all the narratives of Irelands history. As I explored the different ways that family legend intersected with public myth, I became more and more interested in how stories were made, why some things were recorded and others forgotten, the merging of fact with fiction, the invention of memory.