You are not long out of the railway station before you catch the desired view: the enchanting old windmills one white, one black on the crest of the hill, like odd little boats with bright wooden sails riding a giant green wave. A map is scarcely necessary, your destination can be in no doubt. The authorities have fallen over themselves to pepper the road with brown signs that point insistently. They gesture to the South Downs, as if to say: Well why else would you be here?

The initial stretch of railway-hugging concrete pathway is slightly urinous in smell, but bordered on the other side by delicate woodlands, throbbing with bluebells on this sunny spring day. It is a trifling nuisance, this blistered tarmac cut-through that discreetly ushers you out of the Sussex town of Hassocks; a tiny price to pay for the goal that lies ahead. A mile later, you look right up again, at the green hill with its white skeleton of chalk beneath. You rejoin the South Downs path, with more of those signs urging you on; you gaze up at that distant ridge, and the sky above that with all its pale blue promise. No one who considers themselves to be any kind of a walker could conceivably hold back.

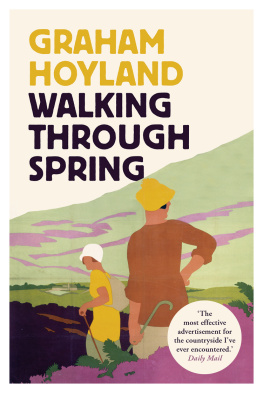

The old childrens story formulation over the hills and far away is one of the most evocative phrases in the English language. It expresses that impossibly ancient curiosity and yearning for adventure; there is also, somehow, the possibility of transformation. Any rambler will also know that the phrase has a physical truth; that when one is walking across a great plain towards hills, the urge to see beyond them becomes magnetic, instinctive. To stop, to turn, to go back requires a powerful exertion of will. So here I am, after a short, rigorous climb, by those old windmills called Jack and Jill, but gazing at yet more green ridges above. This is the South Downs Way, in the South Downs National Park. It is the most recent of such Parks, having attained this special status in 2009. This path is a superb and beautiful tribute to a movement that has been campaigning not merely for decades but centuries.

On a day such as this, with a refreshing but subtle breeze, and the sun dazzling down, the obvious weekend destination for urban fugitives is not here. It is about five miles to the south: the huge majority of the people crammed standing room only on to the train out of London were heading for the beach at Brighton. But we who are up on this ridge and there are a good many of us have a purer purpose in mind. And as we pass one another, on that path that is now snaking around towards Ditchling Beacon, we recognise each other through clothing conventions.

There are the big beige sunhats, with a hint of floppy foppishness; the baggy shorts of indeterminable synthetic fibre; the sturdy boots, laces wrapped around like thick spaghetti. For some, there is also a map, worn around the neck on a lanyard. And having made the effort of getting up this hill as we will see, there is always this Calvinist question of effort we happy few are richly rewarded. This is a ridge of cattle-nibbled grassland the grass is crew-cut, military neat spotted with cakes of sun-dried dung. For those with the eyes and the experience to see, here is ribwort plantain, squinancywort and Devils bit scabious. Meanwhile, dancing and being hurled in random directions by puffs of breeze, are rare butterflies such as the Adonis blue and the Chalkhill blue. Come the summer, there will be the shy, secretive magenta of retiring pyramidal orchids.

This path bright with white chalk is on a gentler upward gradient now, and sweeping across the ridge to Ditchling Beacon. As you walk along this handsome escarpment some 800 feet up, the woods and green fields of Sussex are laid out beneath you, sharp and neat and crisply three-dimensional in the bright sunshine. There are churches and old windmills and manor houses and playing fields; there are also intimations of distant post-industrial warehousing and offices. You are looking at the past and the present simultaneously. Meanwhile, small birds compete in the blowy skies above. The attentive might see linnets, or yellowhammers, or skylarks. There is one elderly couple here with binoculars, lurking by the bushes of bitter-yellow gorse. One assumes they are here for avian reasons, as opposed to human surveillance. You always think the best of your fellow walkers. When seen from a great distance in our walking gear, on hillsides, or marching along the edges of fields we ramblers ourselves look like tiny colourful butterflies milling around on green plant-life. There we go: processing up slopes, in lines, like fluorescent ants. We are the very image of unabashed enthusiasm. Sometimes, the more adverse the conditions, the better. Such dedicated walkers will look out upon stinging rain whipping across bare moorland, take a deep breath of pleasure, then stride forwards and upwards, into the raging storm.

Daniel Defoe, who made a tour of the nation in the 1700s, would have regarded such walkers with some mystification. In the eighteenth century, the only people to be seen tramping across such a landscape either worked it, owned it, or were trespassing on it. The idea that ordinary men and women would simply walk upon it for pleasure and recreation would have struck him as insane. As it was, he was already quite rude enough about those before him who had professed to have seen the beauty in landscapes such as this.

But fashions changed quite soon after Defoe passed away, in fact. In the 1700s, the stern mountains and valleys began to draw poets and painters who were freshly alive to the more sublime aspects of nature. The echoes of their enthusiasm are still heard now. Whether we know it or not, we continue to be influenced by their passions, even if we consider our own regular rambles to be happily quotidian. These days, for a huge number of people, any satisfactory weekend should ideally include a drive out into the country, a loading up of the knapsack with refreshments ready for a good few hours of walking. The ostensible reasons all overlap: the need for some exercise and fresh air after a week sitting in an office, staring at a computer; the desire to see a wider horizon, one not interrupted by houses, tower blocks, or out-of-town supermarkets; and then perhaps the slightly more spiritual sense that it is important to keep in touch with the land itself that by planting our feet on grass and soil, we are reasserting our true, organic natures. Yes, those reasons are certainly part of it. But it goes rather deeper than that.

It is estimated that some 18 million Britons enjoy regular country walks. Less casually, the Ramblers Association has over half a million members. Think of all these people, taking off on Sunday mornings, eager to stride across meadows, and to survey grand views. Think how, just a few generations ago, so many of these people would have been spending Sunday morning in church. Walking is sometimes a form of religious practice in itself; a meditation or even prayer, but at a steady pace. The very idea that there should be an official association for those who enjoy walking is in itself telling. We spend colossal quantities of money on our desire to get mud on our boots. Mud that our forebears would have strenously tried to keep off theirs.

Despite the peaceful, even meditative nature of the pursuit, the story of rambling, as we shall see, is actually a story of constant bitter conflict. It is grand country aristocrats pitted against town-dwelling working class men and women. It is farmers with spring-guns and bone-shattering man-traps dedicating themselves to thwarting those who wish to tread ancient rights of way. It is municipal water boards, hysterically convinced that walkers could infect reservoirs with TB, and doing everything in their power to close off all the land around. It is game-keepers in tweed with heavy sticks neurotically certain that the slightest suggestion of footsteps on the moor would disturb the partridges and plovers. The story of rambling is, in one sense, a prism through which we can view the ebbs and flows of social conflict in Britain, from the Reformation right up to the present day.