Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2019 by Violet Moller

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan, London, in 2019.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Pages 309312 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Cover design by John Fontana

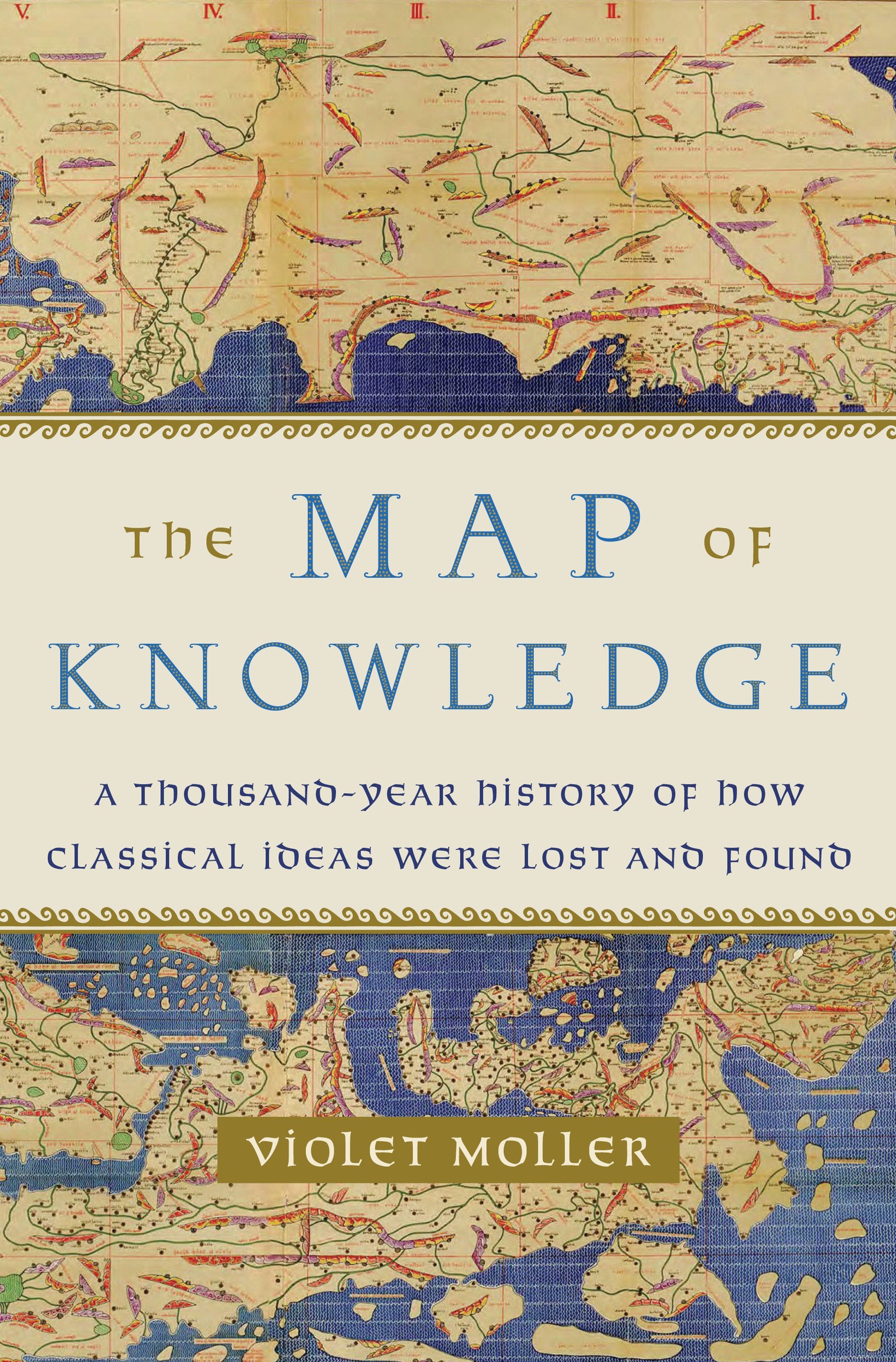

Jacket illustration: The Kitab Rudjdja or Tabula Rogeriana, an early world map by Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created in 1154 for Roger II, King of Sicily (detail). akg-images / WHA / World History Archive

Chapter opener illustrations by Anna Woodbine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moller, Violet, author.

Title: The map of knowledge : a thousand-year history of how classical ideas were lost and found / Violet Moller.

Description: First American edition. | New York : Doubleday, [2019]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018054987 (print) | LCCN 2018060782 (ebook) | ISBN 9780385541770 (ebook) | 9780385541763 (hardcover: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Learning and scholarshipMediterranean

RegionHistoryMedieval, 5001500. | Mediterranean RegionIntellectual

lifeHistory. | East and West.

Classification: LCC AZ231 (ebook) | LCC AZ231 .M65 2019 (print) | DDC 001.209182/dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018054987

Ebook ISBN9780385541770

v5.4

ep

To L, E and S, my three little stars

Contents

Preface

IN EARLY 1509 , the young artist Raffaello Sanzio (14831520) began painting a series of frescoes on the walls of Pope Julius IIs private library, deep inside the Vatican. Next door, in the Sistine Chapel, Raphaels great rival, Michelangelo, lay on his back on a huge scaffold, hundreds of feet in the air, painting onto the ceiling a monumental image of God giving life to Adam. The Renaissance was in full swing in Rome and, under the patronage of Pope Julius, the great city was being returned to the glory of its ancient imperial past. Raphaels frescoes on the four walls of the Stanza della Segnatura illustrated the four categories of books that were shelved below them: theology, philosophy, law and poetry. In the philosophy fresco, which we now call The School of Athens, The architecture is decidedly Romanbold, imperious, monumentalbut the culture and ideas represented by the fifty-eight figures carefully grouped across the painting are emphatically and almost without exception Greek; it is a celebration of the rediscovery of ancient ideas that were central to the intellectual milieu of sixteenth-century Rome. Plato and Aristotle stand in the very centre, under a huge arch, silhouetted against the blue sky, which Plato points up to, while Aristotle gestures to the earth below him, neatly representing their philosophical tendenciesthe formers preoccupation with the ideal and the heavenly, the latters determination to understand the physical world around him. The full scope of ancient philosophy as inherited by Italian humanism is triumphantly rendered in glowing colour.

No one knows exactly who all the other figures in the fresco are, and arguments over their identities have kept scholars occupied for centuries. Most people agree that the bald man in the front right, busy demonstrating geometrical theory with a compass, is Euclid, All the figures identified lived in the ancient world, at least a thousand years before Raphael began painting the frescoexcept for one. On the left of the painting, a man wearing a turban is leaning over Pythagoras shoulder to see what he is writing. He is the Muslim philosopher Averroes (11261198)the single identifiable representative of the thousand years between the last of the ancient Greek philosophers and Raphaels own time, and the single representative of the vital, vibrant tradition of Arab scholarship that had flourished in this period. These scholars, who were of various faiths and origins, but were united by the fact that they wrote in Arabic, had kept the flame of Greek science burning, combining it with other traditions and transforming it with their own hard work and brillianceensuring its survival and transmission down through the centuries to the Renaissance.

I studied Classics and history throughout my time at school and university, but at no point was I taught about the influence of the medieval Arab world, or indeed any other external civilization, on European culture. The narrative for the history of science seemed to say, There were the Greeks, and then the Romans, and then there was the Renaissance, glibly skipping over the millennium in between. I knew from my medieval-history courses that there wasnt much scientific knowledge in Western Europe in this period, and I began to wonder what had happened to the books on mathematics, astronomy and medicine from the ancient world. How did they survive? Who recopied and translated them? Where were the safe havens that ensured their preservation?

When I was twenty-one, a friend and I drove from England to Sicily in her old Volvo. We were researching Graeco-Roman temples for our third-year dissertations. It was a great adventure. We got lost in Naples, hot in Rome, we were pulled over by the police and asked out on a date, we gaped at Pompeii and ate milky balls of buffalo mozzarella in Paestum, and finally, after weeks on the road and a short ferry trip across the Straits of Messina, we arrived in Sicily. The island immediately felt different from the rest of Italy: exotic, complicated, compelling. Its layers of history enveloped us; the marks left by succeeding civilizations, like strata in a rock face, were striking. In Syracuse Cathedral, we saw the columns of the original Greek Temple of Athena, built in the fifth century BC , still standing 2,500 years after they were erected. We learned how the cathedral had been converted into a mosque in 878, when the city came under Muslim control, and how it became a Christian church again two centuries later, when the Normans took power. It was clear that Sicily had been a meeting point for cultures over hundreds of years, a place where ideas, traditions and words had been exchanged and transformed, where worlds had collided. The focus of our trip was the relationship between Greek and Roman religion and architecture, but the contribution of later culturesByzantine, Islamic, Normanwas remarkable. I began to wonder about other places that had played a similar role in the history of ideas, and how those places had developed.

These questions resurfaced when I was researching my PhD on intellectual knowledge in early modern England, viewed through the library of Dr. John Dee (the man Elizabeth I called her philosopher). A strange and captivating character, Dee was my constant companion for several years. He took me on an unforgettable journey through the intellectual world of the late sixteenth century. During his extraordinary career, he amassed the first truly universal collection of books in England, helped plan voyages of discovery to the New World, initiated the concept of a British Empire, reformed the calendar, searched for the philosophers stone, attempted to conjure angels and travelled all over Europe with his wife, servants, several children and hundreds of books in tow. He also wrote extensively on a wide range of subjects: history, mathematics, astrology, navigation, alchemy and magic. One of his most significant achievements was helping to produce the first English translation of Euclids