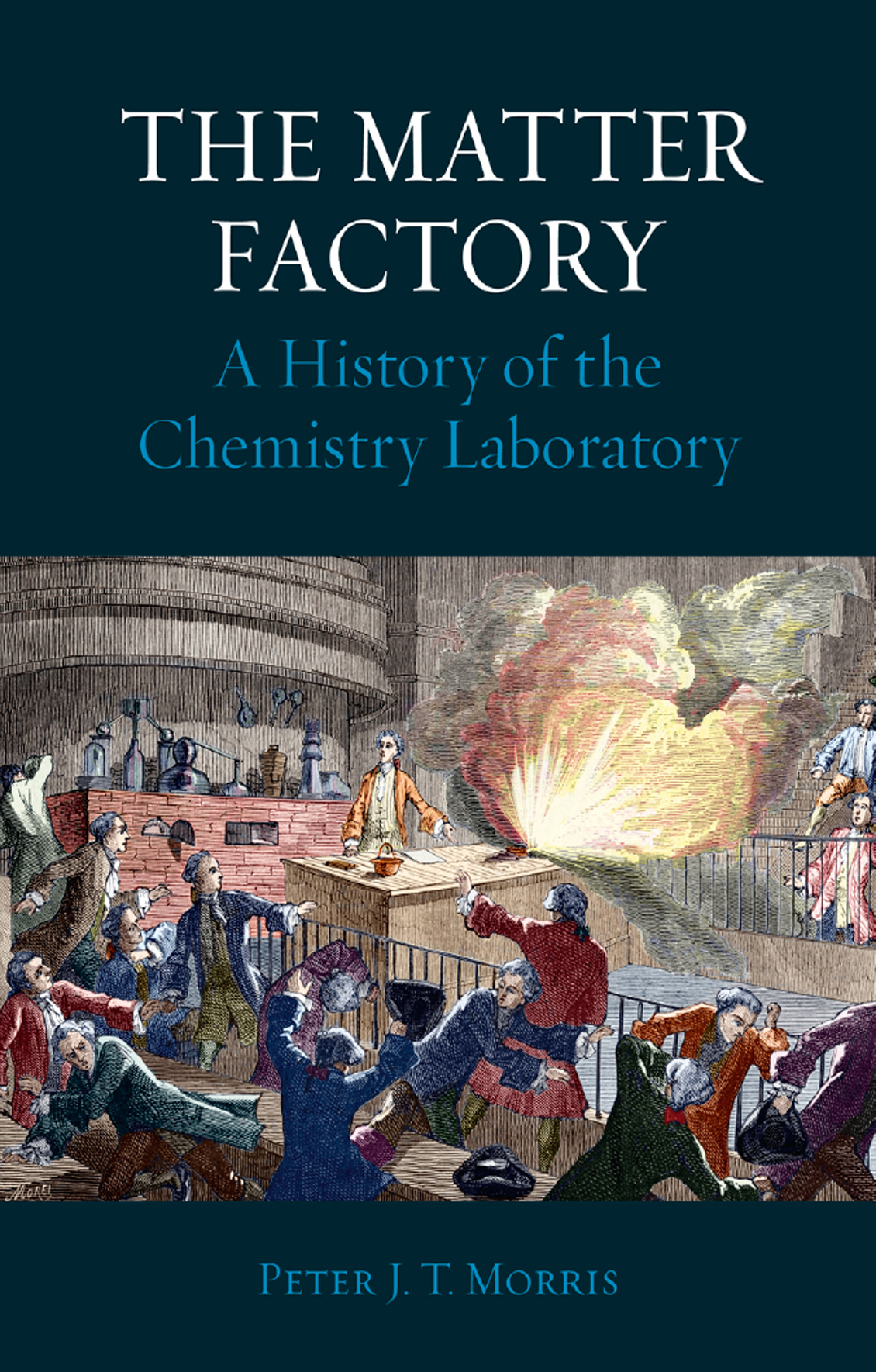

THE MATTER FACTORY

THE MATTER

FACTORY

A History of the

Chemistry Laboratory

P ETER J. T. M ORRIS

REAKTION BOOKS

This book is dedicated to the memory of three departed friends who were true chemists and good historians: W. Alec Campbell (19181999), Colin A. Russell (19282013) and Frank Greenaway (19172013)

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

In association with

Science Museum

Exhibition Road

London SW7 2DD, UK

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

First published 2015

Copyright SCMG Enterprises Ltd 2015

Science Museum SCMG

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234748

Contents

1

Birth of the Laboratory: Wolfgang von Hohenlohe and Weikersheim, 1590s

2

Form and Function: Antoine Lavoisier and Paris, 1780s

3

Laboratory versus Lecture Hall: Michael Faraday and London, 1820s

4

Training Chemists: Justus Liebig and Giessen, 1840s

5

Modern Conveniences: Robert Bunsen and Heidelberg, 1850s

6

The Chemical Palace: Wilhelm Hofmann and Berlin, 1860s

7

Laboratory Transfer: Henry Roscoe and Manchester, 1870s

8

Chemical Museums: Charles Chandler and New York, 1890s

9

Cradles of Innovation: Carl Duisberg and Elberfeld, 1890s

10

Neither Fish nor Fowl: Thomas Thorpe and London, 1890s

11

Chemistry in Silicon Valley: Bill Johnson and Stanford, 1960s

12

Innovation on the Isis: Graham Richards and Oxford, 2000s

1 Painting of an ICI analytical chemistry laboratory, 1957, by Ernest Wallcousins.

Introduction

The idea for this book was born in a seminar room in the Department of the History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania, in Edgar Fahs Smith Hall. This building was named after a famous historian of chemistry and was formerly a pioneering hygiene laboratory the Lea Institute of Hygiene built in 1891. Sadly the building was demolished in 1995 to make way for a new wing of the neighbouring chemical laboratory, despite strenuous opposition from the historian of biochemistry Robert Kohler. The walls of the room were lined with PhD theses, and in 1985 I was reading about the chemistry department of the University of Illinois at Urbana in P. Thomas Carrolls thesis. The present book is a much-expanded version of my study of four laboratories for that chapter.

As a historian and curator I believe that the history of chemistry has to be more than just the history of chemical theories; it has to include the history of chemical practice and chemical culture. Laboratories are an important part of that practice and culture. They are the places where chemists are trained and where many of them spend their careers. They are where chemistry is carried out from the freshmans first inorganic analysis to the most complex of organic syntheses. I have argued elsewhere that historians of chemistry have failed to meet the needs of chemists.

Rather surprisingly, as Kohler has pointed out,

There is the fundamental question of what a chemical laboratory is.

My aim is to describe how laboratories and laboratory buildings have changed to meet the differing needs of chemistry from 1600 to 2000. I will show how the form of the laboratory has altered over the years to accommodate the functions of chemistry at the time it was constructed. However, it is not just a matter of the laboratory being shaped by chemistry. The new opportunities offered by the most modern laboratories have allowed chemistry to progress; for example, the arrival of coal gas in the laboratory assisted the invention of the Bunsen burner, which in turn enabled the development of spectroscopy. Chemistry pushes the development of the laboratory, and the improved laboratory in turn enables chemistry to move forwards. It is the ambitious chemistry professor who ensures that the two lines of development reinforce each other. As a leading chemist, he (and until recently it was invariably a he) knows what changes need to be made to the laboratory to do cutting-edge chemistry. He also knows what kind of chemistry the new laboratory will make possible. In the absence of such professors the development of the chemical laboratory would have been much slower.

It is clear that competition between individuals and nations is one of the driving forces of laboratory development. At the same time there is much cooperation between chemists (and their architects) across national boundaries. The architect of Bunsens laboratory designed a laboratory for an American college. France may have been compelled by the German ascendency in chemistry to build a new laboratory building at the Sorbonne in the 1890s, but (August) Wilhelm Hofmann was happy to spend days with Henri-Paul Nnot, the French architect, on the plans for this building. Nonetheless the main aim of these innovators was to do better and as we shall see, safer chemistry. I have deliberately eschewed any notion of an evolution of the laboratory. Moreover, to avoid any accusations of Whiggism, I have written a chapter on chemical museums to show how certain features of the nineteenth-century laboratory have not survived in any form today.

This is a history of the chemical laboratory as a room or building containing chemists, not as a rhetorical (or actual) space in which various human and non-human actors operate ( The external architectural style of the building tends to reflect current fashions (Romanesque or glass plate), without much impact on the internal arrangements. What matters, I would argue, is the sizes and shapes of the various rooms and their relationships to each other.

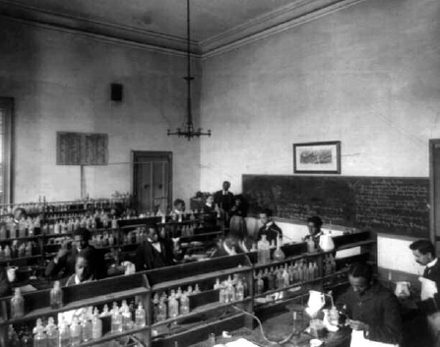

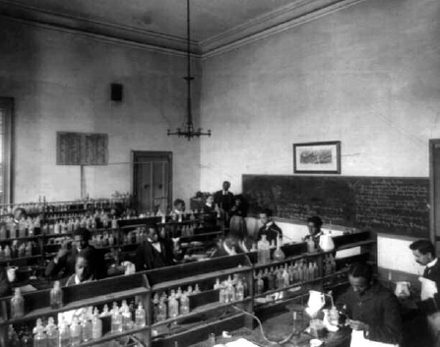

2 Chemistry laboratory at Howard University, Washington, DC, c. 1900. The laboratory design created in Germany in the 1850s and 60s had become universal by 1900.

My main method of analysis has been the close study of pictures of the interiors of the laboratories and their ground plans. Other sources were not readily available. Archival sources are sparse, widely dispersed and too time-consuming for a history on this scale. The descriptions in the literature are useful and have been used, but are no substitute for the actual illustrations. The buildings themselves have been changed over the years (when they have survived at all), and any reconstruction has to be treated with considerable reserve. As far as I can tell, however, most illustrations of laboratories are reasonably accurate and suffice for the purposes of this book.

I was eager for this book to be more than just a history of the chemical laboratory. To provide the context for the laboratories discussed, I have described the backgrounds to their construction, noting national factors where relevant, and sketched the chemical developments that are most pertinent to them. I have also sought to capture the development of chemical practice by having a section on an appropriate technique in each chapter. Acknowledging that the human element adds colour to any narrative and that personality plays an important role in the history of chemistry, I have additionally given a brief biography of a key chemist in every chapter. Unusually in a work of this kind, I have made some autobiographical remarks because my own experience of laboratories seems relevant to understanding what happens in one something that is very hard to capture solely from documents or pictures.