The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

People think of history in the long term, but history, in fact, is a very sudden thing.

That was a small lesson I learned on the journey. What is interesting and important happens mostly in secret, in places where there is no power.

November 10, 1938: Tove Gerson brought flowers. In Essen as elsewhere in Germany during the previous nightKristallnacht, as it came to be knownJewish homes, businesses, and places of worship had been ransacked and destroyed, and their occupants terrorized. Violence continued to swirl and eddy in neighborhoods across the city. Tove, herself not Jewish, had come to check up on the Heinemanns, a wealthy and cultured Jewish couple, now retired. Tove had met them through her parents-in-law and had attended many a chamber concert in their imposing villa. On the square outside the Heinemanns home, Tove was confronted by a baying mob. A slight and, by her own admission, somewhat fearful woman in her mid-thirties, Tove found herself barked at for bringing flowers to the Jews. She stammered some excuse, fought her way through the crowd, and made it inside, where she found the aging couple cowed and crushed amid the torched paintings and shattered glass of their home.

December 4, 1939: Sonja Schreiber spoke up. Ever since the Wehrmacht had invaded Poland in September, stories about atrocities had been circulating in Germany. News bulletins reported the massacres Poles had ostensibly perpetrated against the Germans and the actions the Germans had carried out as reprisals. Sonja, an elementary school teacher in Essen in her mid-forties, was also working as a volunteer at the local ration office and found herself engaged in conversation by a Frau Gross, a fellow volunteer. When it came to atrocities, Frau Gross said, she knew who was really responsible: the Jews. Sonja, gentle and idealistic, someone almost too navely good to impose order on the classroom, could not stand this twaddle, and spoke up strongly in defense of the Jews as a persecuted people. A shocked Frau Gross told her husbandand her husband told the Gestapo.

November 8, 1941: Artur Jacobs brought a woman to tears. Artur, a spritely sixty-year-old former teacher in Essen with time on his hands, had made it his business to follow the worsening fate of Germanys Jews. Over the last few weeks he had registered with dismay the first major deportations from his region. Ignoring the increasingly severe sanctions against those who helped Jews, Artur ventured what moral and physical support he could. When a Frau K, about to be deported to Minsk, thanked him for his solidarity, Artur said it was he who should be thanking her. She had given him a chance to discharge some of the guilt he felt at what was happening to his fellow countrymen. At this point Frau K broke into tears. You have no idea what consolation you have given me.

December 1942: Else Bramesfeld took a risk. Back in April, her Jewish friend Lisa Jacob had been assigned to a deportation and since then had been hiding in plain sight. From time to time Else sheltered Lisa. Now, however, Else offered something more, a lifeline in the form of an official piece of ID that Lisa could present when asked for her papers on a train or tram. Else had obtained it by writing to her professional teachers association, saying she was on holiday and had lost her ID card. In requesting a replacement, she included a photoof Lisa. The association never caught on to the ruse and duly mailed back a new ID card bearing Elses name and Lisas likeness. It was, as Lisa would later write, a priceless Christmas present, one that lightened the psychological load every time Lisa had to move between addresses.

February 1944: Grete Dreibholz disclosed a forbidden friendship. Forty-seven years old, the daughter of a prosperous businessman in the manufacturing town of Remscheid, until 1933 Grete had been passionately involved in Remscheids left-wing scene. Her beloved sister, Else, another free spirit, married the well-known playwright Friedrich Wolf, a Communist Jew, and followed him to the Soviet Union after the Nazis came to power. Under the Nazis, Gretes radical connections became a liability. She was dismissed from her well-paying administrative position and took up factory work to make ends meet. By 1943 she was working alongside Polish and Russian forced laborers housed in appalling conditions. Ignoring the risks, she befriended their interpreter, a formerly well-to-do woman from Warsaw. In a letter in February, Grete wrote about this friendship, describing with a fearless lack of self-censorship what the forced laborers endured. If it had not been for the clothes she had found for the interpreter and her daughter, she wrote, they would have had literally nothing to wear.

July 29, 1944: Hermann Schmalstieg opened his home. Hermann was a handsome, romantic thirty-something, a working-class boy who had managed to qualify as a master craftsman in precision engineering. The Great Depression had made it hard to find a job, and he eventually landed a position as a technician at the Braunschweig Technical Universitys Acoustics Institute. During the war, the institute was employed on military contracts and moved to an isolated site on the Auerhahn Mountain, in the Harz Mountains near Goslar. Here Hermann had use of a lonely foresters cottage. Friends asked him if he would allow a young woman on the run to take refuge there for a while. And so, toward the end of July, a twenty-one-year-old Jewish woman, Marianne Strauss, came to stay with him in the cottage for a few days.

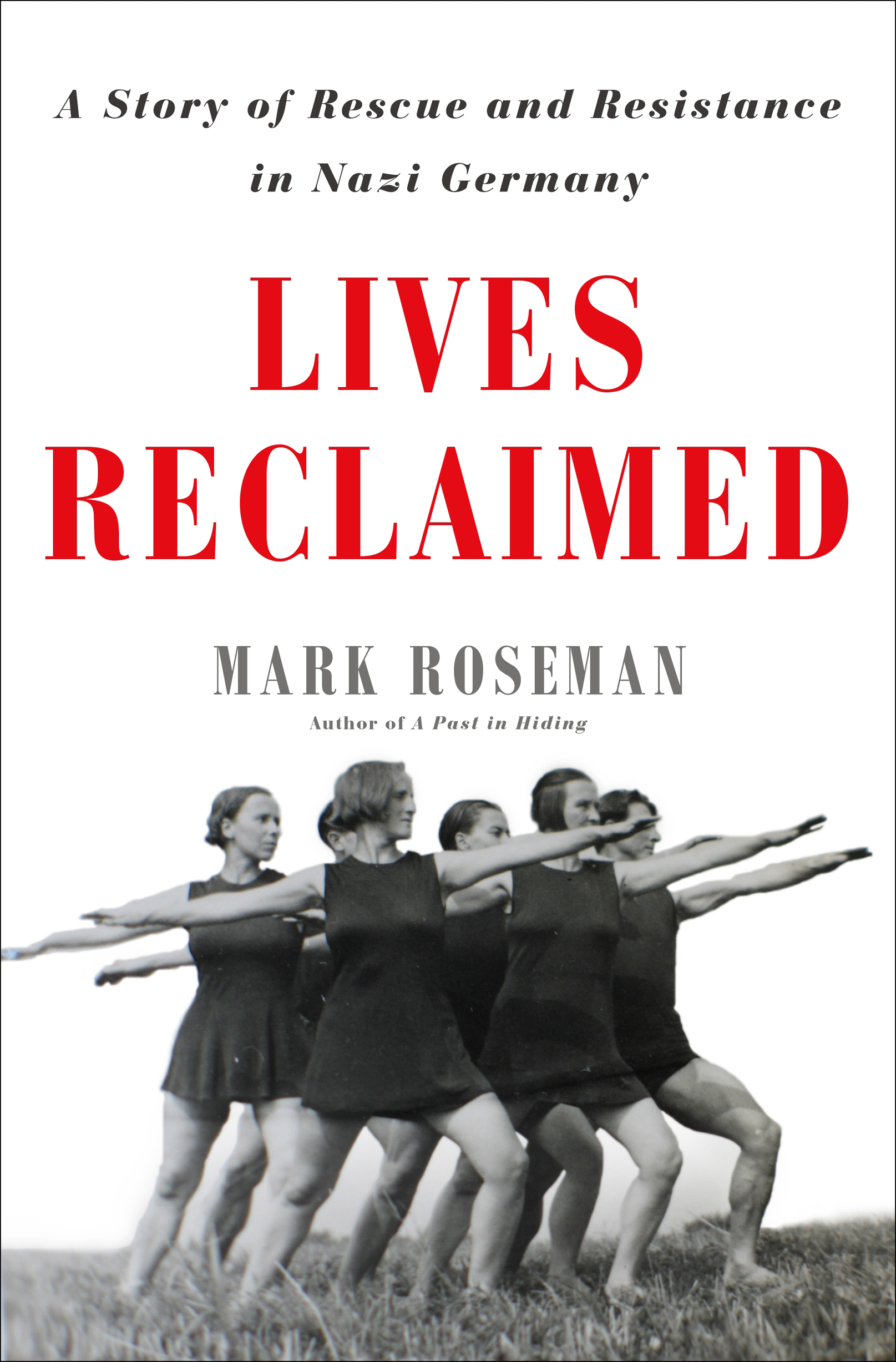

Lives Reclaimed is about a small group of idealists living in Nazi Germany, many of them women, who recognized the plight of others and acted on that knowledge, despite the risks of retribution. Tove, Sonja, Artur, Else, Lisa, Grete, and Hermann were all connected to the Bund: Gemeinschaft fr sozialistisches Leben. The name translates to League: Community for Socialist Life, but its members referred to it, simply, as the Bund. Although they have been largely unheard and unseen till now, the record of their voices and actions has nevertheless been preserved. This book looks at not only what they did but also what motivated them to reach out to others, including complete strangers, and how they found the freedom and courage to act. It explores the consequences of their actions for those who received their help and for the helpers themselves, both during and after the war.

Even in the rarefied company of the few groups that helped Jews in Nazi Germany, the Bund stands outnot least because it was not in any sense created to oppose the Nazis. It both predated and outlasted the regime. When originally formed in 1924, amid the cooling hopes of the Weimar Republics revolutionary years, the Bund had no conception of the brutal dictatorship that was to come or any sense that within a decade its members would be living a life of danger and clandestine action. For many on the left, the climate in 1924 was still one of optimismalbeit tempered by the recognition that achieving social transformation would take longer than expected. Based in the Ruhr, and founded by some of the teachers and pupils at Essens adult education institute, the Bund grew to perhaps as many as two hundred membersworkers, teachers, middle-class women with a social conscience, and others, among them quite a few Jews. Through meetings, joint study, physical exercise, and excursions, this new group sought to develop a holistic and uplifting communal life. It also reached out to others through adult education, experiments in alternative schooling, gymnastics training, and political meetings. Its members were hoping to be the crucible for a future, better Germany. They were certainly not preparing for life under a future fascist dictatorship.