Here I come, a ferryman without a body

To the great flowing river.

If you pay the price

Your mind

That grasps and lets go,

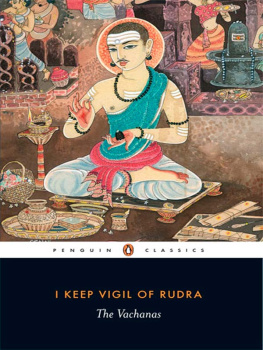

I shall take you across. Vachana poetry in Kannada literature attained its zenith in the twelfth century. Passionate, intensely personal and ahead of their times, these free-verse poems speak eloquently of the futility of formal learning, the vanity of wealth and the evils of social divisions. The vachanas stress on the worship of Shiva, through love, labour and devotion, as the only worthwhile life-goal for the vachanakarathe vachana poet. This collection offers a selection of vachanas composed by a wide range of vachanakaras from different walks of life. While some of these poets are well known even today, most have been forgotten. Translated fluidly and with great skill by H.S.

Shivaprakash, I Keep Vigil of Rudra is not only an important addition to vachana literature, but also a must-read for lovers of poetry everywhere. Translated by H.S.SHIVAPRAKASH Cover: Basavanna by S. Rajam, watercolour on paper, 1970.

I KEEP VIGIL OF RUDRA

The Vachanas

Translated with an introduction by

H.S. Shivaprakash

PENGUIN BOOKS UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection published 2016 Copyright H.S.

Shivaprakash 2010 The moral right of the author has been asserted ISBN: 978-0-143-06357-5 This digital edition published in 2016. e-ISBN: 978-8-184-75283-0 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

PENGUIN BOOKS

I KEEP VIGIL OF RUDRA

H.S. Shivaprakash is a well-known poet, playwright and translator from Karnataka. His translations and adaptations of Shakespeare are widely staged. He has also translated major European, Latin American and African poets into Kannada and some of the best-known Kannada and Tamil poets into English.

He is the winner of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for play-writing and four best book prizes of the Karnataka Sahitya Akademi for poetry and translations. A former editor of the translations journal Indian Literature, Shivaprakash is an honorary fellow of the School of Letters, University of Iowa, and a specialist in Indian devotional traditions. He is currently professor, Theatre and Performance Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. To my guru of gurus

Shree Shivalinga Mahaswamy,

A name without form

Fragrance without colour

And

Light

Everywhere

Acknowledgements

Without togetherness, no joy of joys Akkamahadevi Though I have been working on these translations for over twenty-five years, they would not have seen the light of day but for the help and support of many friends and well wishers. It was the late Professor P. Ramamurthy who suggested I translate vachanas as part of my Ph.D thesis.

It was unfortunate that he passed away before seeing it completed. My Ph.D supervisor Professor C.N. Srinath gave me many useful suggestions about translation during my Ph.D years. In those days when the computer was unknown, Sandhya worked very hard to make copies of several drafts of my translations. My encounter with Professor Daniel Weisbort, former editor of the influential journal, Poetry in Translation, at a workshop in Bhopal helped me gain many insights into the art of translation. He also pointed out that after A.K.

Ramanujan had introduced vachanas to English readers with his brilliant translations, there was a need for more specialized versions of these texts. He inspired me to rethink my translations. It was in Iowa city in 2000 that I nearly finalized my translations with the generous help of the young American poet Parker Smothers who was introduced to me by my friend Philip Lutgendorf. This would not be possible had Professor Peter Green not got me invited to the International Writing Workshop that year. My former student, Manu Devadevan, himself a poet and translator of great merit, lent invaluable help in tidying up the translations and the introduction. It was during the course of a discussion with him that it occurred to me that the vachanas should be arranged not author-wise, but in a dialogic fashion.

There is a great tradition of vachana lovers and scholars right from the twelfth century to the present who, by the dint of their hard labour, preserved and prevented the vachana texts from passing into oblivion. After the coming of printing technology, a whole tradition of textual scholars that includes Basavanal, Halakatti, R.C. Hiremath, M.S. Sunkapur, Ja. Cha. Ni., L.

Basvaraju, S. Vidyashankar went on trying to improve the existing versions of these texts with their painstaking scholarly labour. Every translator has to acknowledge their enormous labour in making the vachanas available to us in the present form. When I had almost given up hope of getting my translations published, my friends Mahalakshmi and Rakesh rekindled it, and Ravi Singh offered to publish them. My editors Sivapriya and Anurag have worked on these texts with loving care.

Introduction

Alas! They make versions of versionless non-version.

Introduction

Alas! They make versions of versionless non-version.

Allama Prabhu

Historical Context

Medieval Kannada literature spans a period of about seven centuries from the beginning of the twelfth century. However, the borders of this period are sometimes pushed back and forth. For instance, some historians consider Muddanna, the famous poet who saw the birth of the twentieth century, as part of medieval literature whereas the Tatvapadakaras of the eighteenth century are regarded as the precursors of modern Kannada literature. Historically, these centuries saw many dramatic events on the socio-political and cultural frontiers of Karnataka. Among other things, the period saw the fall of the Chalukyas of Kalyana, the meteoric rise and disappearance of the Kalachuryas, and the ups and downs of the Hoysalas of Dorasamudra. These events roughly characterized the political landscape of the first two centuries of the medieval period.

The most important event during the later centuries was the setting up and consolidation of the Vijayanagara empire. The rise of the Bahmani sultanate of Bijapur and the emergence of smaller kingdoms and fiefdoms like those of Bidanur, Mysore and of the Keoadi family also took place during this period. Of all these developments, the Kalachurya and Vijayanagara empires made the greatest difference to Kannada language and literature. The heroes of medieval narrative poems were not military heroes any more, but spiritual heroes. The form of narrative poetry also underwent a sea change, thanks to the bhakti movement. The greatest narrative poets of the previous age, with minor exceptions, employed Champu, a genre characterized by Sanskrit metres.

The medieval narrative poets resorted to simpler vernacular metres like Shatpadi, Sangatya and Tripadi. Bhakti movements were not without their negative effects. Many of the lesser poets took spiteful sectarian propaganda to be the main task of poetry and produced mediocre work. This is a weakness that has at times diluted even the works of otherwise great poets like Basavanna and Harihara. The pervasive influence of the bhakti movements limited the content of literature to the religious. Only the greatest poets of the period like the Vachanakaras and Haridasas at their best, and Kumaravyasa, are free from the stigma of sectarianism.

PENGUIN BOOKS UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

PENGUIN BOOKS UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia