FREEDOM AND THE CAGE

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Topp, Leslie, 1969 , author.

Title: Freedom and the cage : modern architecture and psychiatry in Central Europe, 18901914 / Leslie Topp.

Other titles: Buildings, landscapes, and societies.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2017] | Series: Buildings, landscapes, and societies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Explores the issues surrounding the architectural design of insane asylums in the late nineteenth-century Habsburg Empire, including the paradox of maximizing individual freedom within an environment of involuntary confinementProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016034219 | ISBN 9780271077109 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: lcsh: Psychiatric hospitalsEurope, CentralDesign and constructionHistory19th century. | Psychiatric hospitalsEurope, CentralDesign and constructionHistory20th century. | Hospital architectureEurope, CentralHistory19th century. | Hospital architectureEurope, CentralHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC RC 450. E 8 T 67 2017 | DDC 725/.52094dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016034219

Copyright 2017 The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the China

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

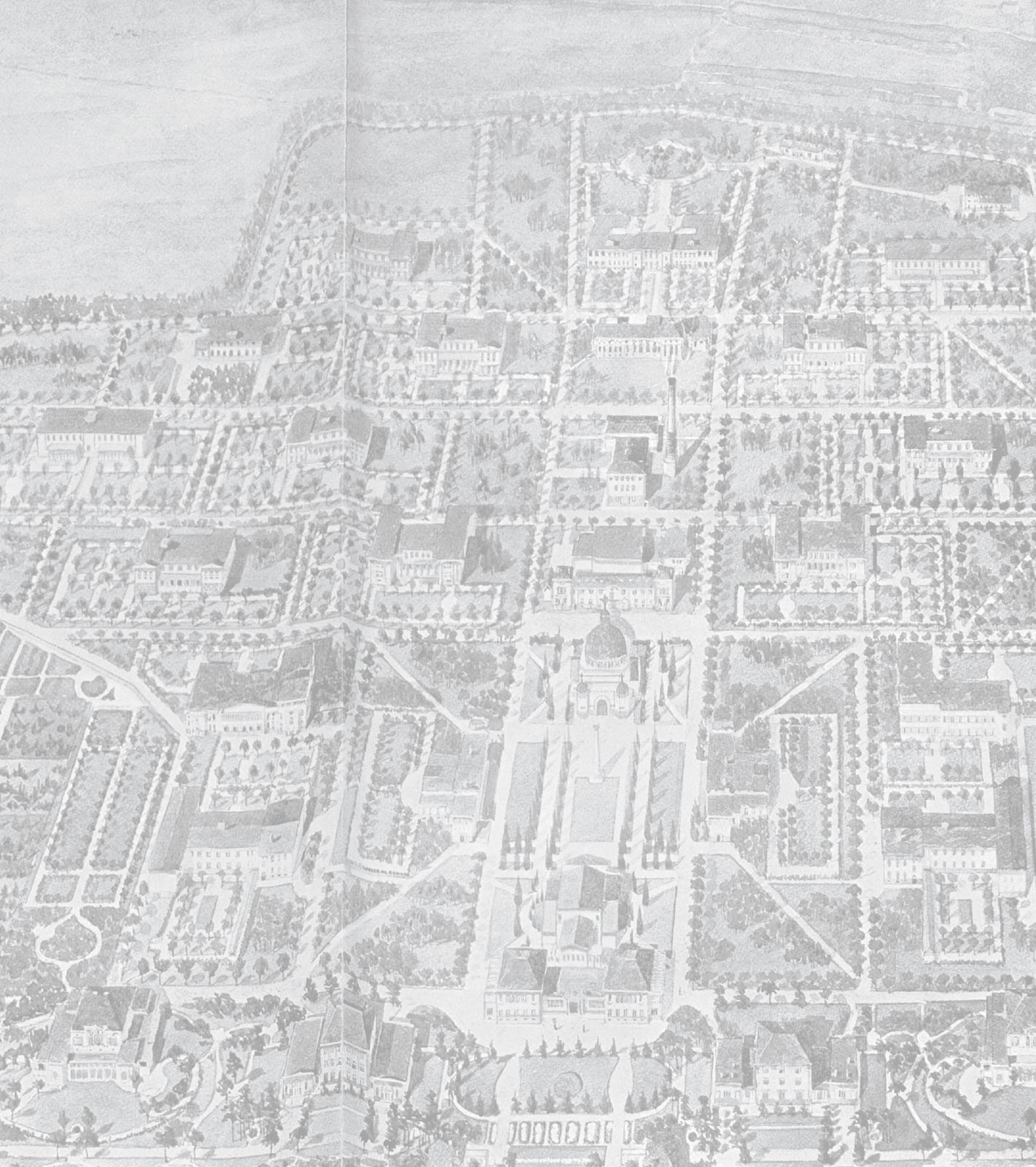

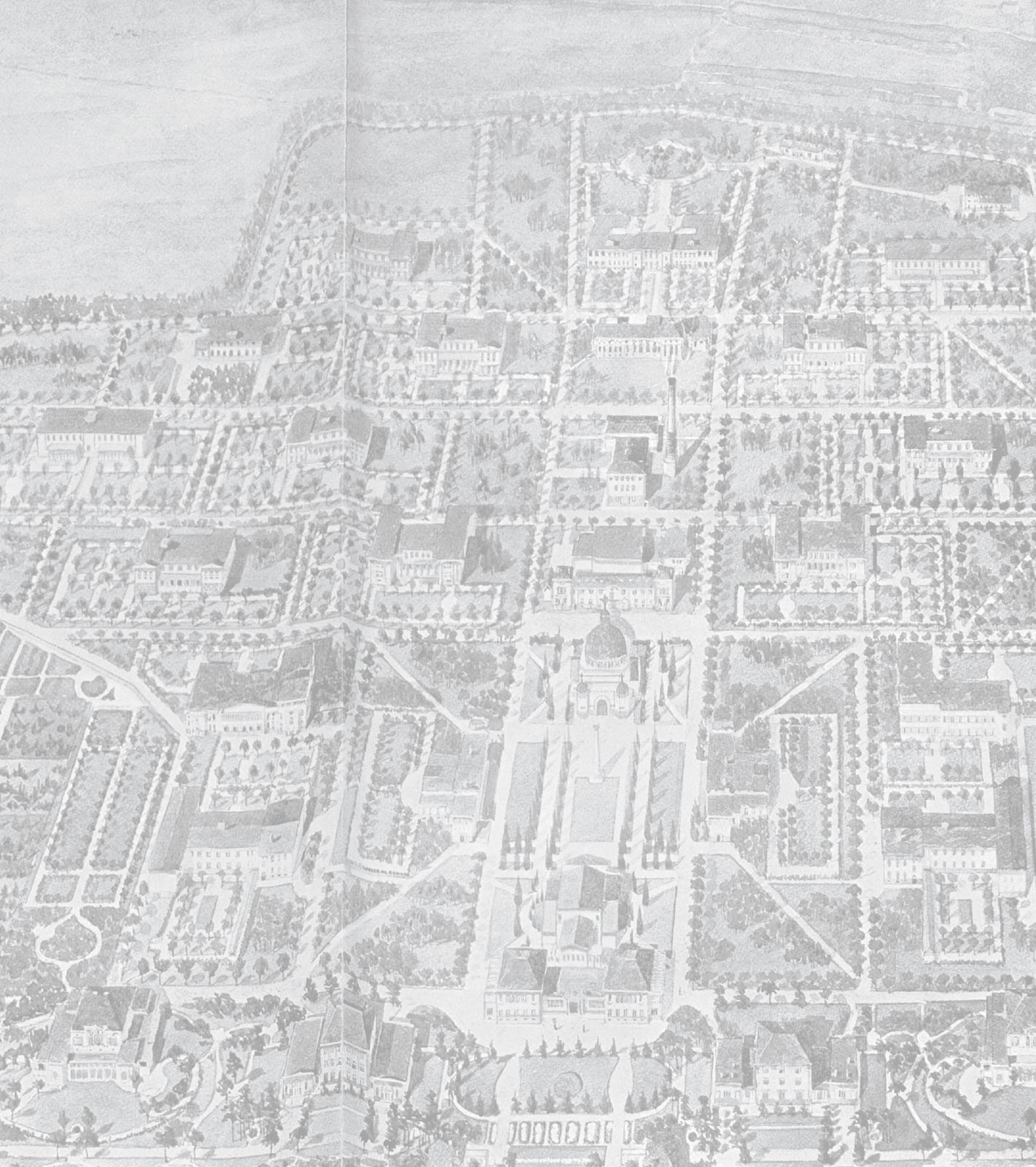

Frontispiece: detail of Moravian Crown-land asylum, Krom, birds-eye view ().

for Neil

CONTENTS

I HAVE BEEN lucky enough not to have spent time as a patient in a psychiatric hospital, but I have had friends and relatives who have experienced institutionalization, in some cases for many years. People have often asked me over the long course of this project what brought me to work on the topic of asylum architecture, and Ive talked about the discoveries and connections made during my research at Bryn Mawr College and in Vienna in the 1990s, and specifically my work on Josef Hoffmanns Purkersdorf Sanatorium, a private institution for sufferers from nervous ailments, built in the Vienna Woods in 1904. These were the conventionally academic origins of this book. But what has sustained my attention over the many years needed to complete it is the conviction that the problem of the asylum as a built and landscaped environment designed at once to transform, control, and liberate is alive and unresolved. People like my friend with bipolar disorder, who bounced back and forth between her parents home and the Clark Institute of Psychiatry, a high-rise block in the middle of the University of Toronto campus, experience the terror and confusion of mental illness in highly meaningful and culturally loaded physical environments, even if they are no longer the bounded communities of isolated asylums. And the boundaries of the bounded community are still very much present, surrounding, for example, the home where my uncle lived the last years of his life, along with others suffering from dementia. It was called Liberty Place.

Several of the institutions studied in this book are still operating as psychiatric hospitals, and my first word of thanks goes to both the patients and the staff there, for tolerating and indeed facilitating my visits and inquiries. Without the generous help given me by busy people at the hospitals themselves, I would have struggled even more to come to grips with the spaces of these complex institutions; they also kindly gave me access to many original images and documents. At the Otto-Wagner-Spital (formerly Steinhof), in Vienna, I was assisted by Paul Keiblinger, Robert Hutfless, and Katharina Baier, and Professor Eberhard Gabriel, former medical director of the hospital, to whom I am particularly grateful for his willingness to share his own historical expertise and discoveries and for his patience in answering my many inquiries. My thanks as well to Leopold Dirnberger at the psychiatric clinic at Mauer-hling, Maciej Bbr at the Babinski Hospital in Krakow (formerly the asylum at Kobierzyn), Jan Plka at the psychiatric hospital at Krom, Dr. Bruno Norcio at the Department of Mental Health in Trieste, Dr. Mario Novello at the Department of Mental Health in Udine, and Libuse Krausova at the Prague psychiatric hospital, for their time and assistance.

This book has been continually nourished by collaborations and discussions with colleagues and friends. Sabine Wieber, who was a research associate on the 20048 project from which this book stemmed, has been a constant source of support and stimulation and a partner in dialogue; her contributions are evident throughout the book, in the archival and on-site research, in the photography, in the ideas, and in the final refinement of the text. I give her my heartfelt thanks. I am also deeply grateful to Gemma Blackshaw for many years of fruitful collaboration, for pointing me to extremely useful material, and for inspiring me to keep visual culture always in mind. Nicola Imrie provided a wider view through her research, as did Luke Heighton, and Khadija Zinnenburg Carroll provided valuable research assistance. I owe Christine Stevenson a huge amount for years of discussion and support and for her rigorous and thoughtful responses to the text. Despina Stratigakos, Tony Evans, Nia Williams, and Barbara Miller Lane have helped me with advice and friendship throughout. The multilingual nature of the project has meant having to rely on many people for help: thank you to Celia Donert for translations from Czech, to Zo Opai for help with Czech inquiries, to Peter Wozniak and Kasia Murawska-Muthesius for translations from Polish, and to Dorigen Caldwell and Patrizia Di Bello for help with Italian; Im grateful too to the many archivists, librarians, and others who patiently endured my clumsy efforts to communicate. Michal Hartl, Radim Rozehnal, Jan Tabor, Anna Soucek, Halyna Bodnar, Katarzyna Jagodzinska, and Monica Bainat all gave invaluable help with research and interpretation in Prague, Brno, Krom, Krakow, Lviv, Trieste, and Gorizia. Warm thanks to Mike Wabb, Doris Wackerle, Cara Morris, and Charlotte Kohn for friendship and places to stay in Vienna on many occasions over the years.

I relied heavily on colleagues for their expertise on the regions, architectures, and institutions discussed in the book and would like to acknowledge the kind assistance given by Jindich Vybral, Roman Prahl, Mirek Ambroz, Wojciech Balus, Zbigniew Dyrdon, Piotr Franaszek, Andrzej Szczerski, Ida Frigo, Cassiano DallAntonia, Marco Pozzetto, Diana Barrilari, Casimira Grande, Markus Kristan, Renata Kassal-Mikula, Andreas Nierhaus, and Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber. As I strayed into the history of psychiatry and medicine, experts in those areas were generous with feedback and answers to myriad queries: Sonia Horn, Sophie Ledebur, Thomas Mller, Eric Engstrom, Kai Sammet, Jonathan Andrews, James Moran, Tatiana Buklijas, Emese Lafferton, Chris Philo, Sarah Rutherford, Louise Hide, Len Smith, and Simon Schaffer. I would also like to thank the editors and peer reviewers who gave such valuable feedback on the articles that fed into the book. Joseph Siry gave essential advice on the issue of redrawn plans, and Helen Jones did a fine job of producing them and a map.