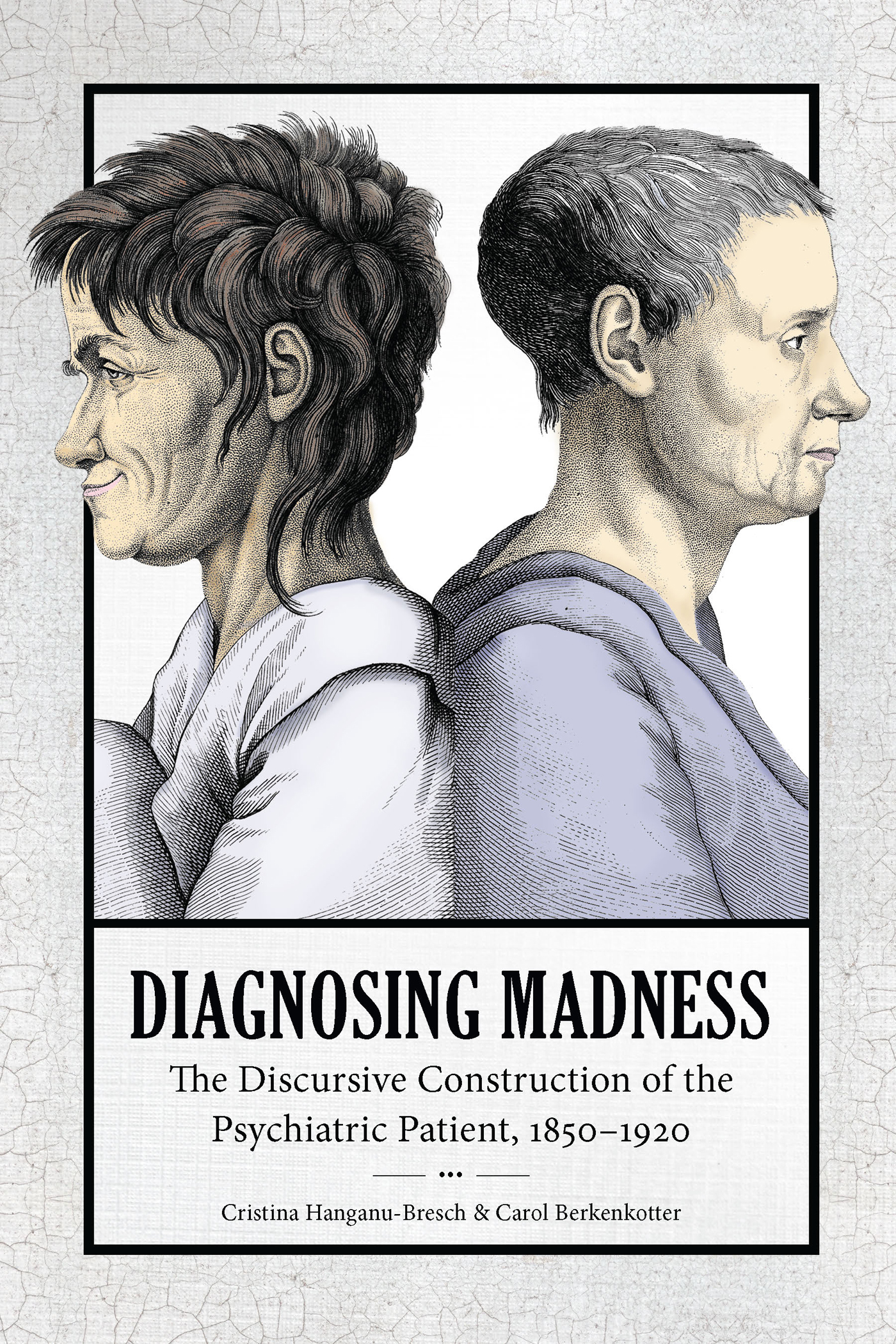

DIAGNOSING MADNESS

STUDIES IN RHETORIC/COMMUNICATION

Thomas W. Benson, Series Editor

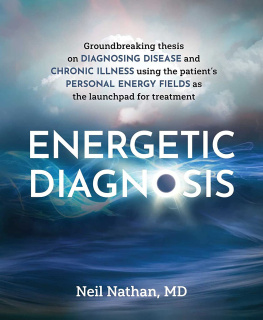

Diagnosing Madness

THE DISCURSIVE CONSTRUCTION OF THE PSYCHIATRIC PATIENT, 18501920

Cristina Hanganu-Bresch

& Carol Berkenkotter

2019 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/.

ISBN 978-1-64336-025-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-64336-026-3 (ebook)

Front cover design by Brock Henderson

To my parents, Marius and Doina, to whom I owe everything, and Art, who believed in me when it mattered,

Cristina Hanganu-Bresch

Madness is a foreign country.

Roy Porter, A Social History of Madness, 1987

The right to restrain an insane person of his liberty is found in that great law of humanity which makes it necessary to confine those whose going at large would be dangerous to himself or others.

Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw, Matter of Oakes, 1845

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

SERIES EDITORS PREFACE

In the nineteenth century, psychiatric practitioners turned to confinement in what were called insane asylums as the remedy for severe cases of mental illness. The practice generated a large body of textual documentation, especially as it was contested, defended, and administered both in the medical community and in society at large. Cristina Hanganu-Bresch and Carol Berkenkotter examine some of resulting texts from a rhetorical perspective, attending to the ways they exercise a rhetoric of medicine, institutional justifications of the administrative, legal, and institutional practices, as well as various forms of resistance to the regime of confinement, including popular fictions of the horrors of wrongful confinement. This is a deeply humane and reflective book, astute in its critical readings and challenging in its affirmation of the humanity of the psychiatric subject.

THOMAS W. BENSON

PREFACE

This book is the result of years of research spent in archives and libraries on two continents in an attempt to decipher the textual footprints of asylum patients. Some of the results of this research have already been published in Carol Berkenkotters book Patient Tales: Case Histories and the Uses of Narrative in Psychiatry, as well as in various journals. Here, we focus on tracing not just the patients medical histories but also their life stories before they became patients and after they were discharged. We find that the diagnosis event is the watershed moment in their lives, and so we are looking for the textualand texturalmakeup of this decision. This was our own version of starring the text, in the words of Alan Gross, of placing rhetorical analysis of the written word at the center of the web of cultural practices that made asylums possible in the nineteenth century; thus, we observe firsthand the psychiatric argumentation practices that led to diagnosis and the patients efforts to counter those arguments. For a while we inhabited a world of fading calligraphy inscribed in esoterically paginated dusty tomes, amalgamated genres that also hosted occasional patient letters and artifacts (drawings, paintings, diagrams, objets dart sometimes engraved in what appeared to be the patients own blood). Whenever possible, case notes, certificates, and private correspondence were copied, transcribed, and analyzed (in some instance coded); and while we used various analytical frameworks, for the most part we let the texts guide us to what we hoped to be intelligible, plausible approximations of the embodied experience of mental illness for those who found themselves in an asylum. We cover both wrongful and rightful confinement here, although as we shall see, both wrongful and rightful are terms laden with judgments and assumptions we may find hard to adhere to today. We look at the English-speaking world (specifically, the United States and Britain) because of their shared philosophy of psychiatric confinement and the commonality of language, and to a period covering roughly the middle of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century, which is also when asylums came under attack from various sectors of the general public. Regrettably, our access to American medical archives has been severely limited because of a restrictive interpretation of laws protecting patient confidentiality; centuries-old asylum archives, containing case notes and worlds that have been only tentatively explored so far, lie beyond our reach. Thus, instead of asylum records, we turned to two other sources: serialized novels and court proceedings, both of which described (and pronounced judgments on) cases of wrongful confinement. The texts we have analyzed here via a variety of heterogeneous methods under the umbrella of rhetoric capture both the larger nuances of historical phenomena and the life details of private citizens caught in the psychiatric system.

We wish to thank the extraordinary librarians at the Wellcome Library for the History of Medicine in London, and in particular to Richard Aspin, the director of Rare Collections, who helped us wade through many square meters of handwritten text. We are also grateful to the Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections staff, in particular Anne Upton, who directed us to the Hinchman archive, which included press clippings and family letters. We would also like to acknowledge the reviewers who helped make parts of this work stronger, in particular the anonymous reviewers for the journals Literature and Medicine and Written Communication, as well as the participants in the Rhetoric Society of Americas 2015 Institute on Theory Building in the Rhetoric of Health and Medicine (especially Jeff Bennett, whose comments on an earlier version of were extremely useful). Last but far from least, we are immensely indebted to Kira Dreher, who, while a research assistant for Carol at the University of Minnesota, helped transcribe and make sense of the Baldwin case notes and contributed a part of that chapter.

It is now time to depart from the plural we. I left the hardest part for last: this book was a difficult project to finish because of the premature illness and death of my coauthor, Carol Berkenkotter. Carol was a shining light in the world of writing studies, a generous, brilliant, beloved scholar who is fondly remembered by her students and colleagues. She was also my mentor, and her work ethic, astuteness, intelligence, and charm will forever be with me. It has been a surreal experience finishing this without her, as she had long set the stage and tone for this research agenda. Thank you, Carol, for sharing your intellect, wisdom, brilliance, and kindness with me and many others who were fortunate enough to work with you.

Cristina Hanganu-Bresch

Introduction

DIAGNOSING MADNESSIMAGINING THE PSYCHIATRIC PATIENT, 18501920

Studies of nineteenth-century psychiatry have generally focused on famous cases, doctors, or paradigm changes and ideological movements. They have more rarely focused on ordinary individual patients cases as they appeared in primary documents such as case notes, admission documents, Medical Certificates, and so on. We believe that the study of such documents can add to our modern understanding of mental illness as it was perceived in the English-speaking world (Britain and America) in the late nineteenth century and how the subsequent treatment of the insane came to be. In particular, we want to understand the struggle to diagnose mental illness, which had momentous consequences for the life circumstances of the diagnosed. The act of diagnosing mental illness was a watershed moment, triggering a cascade of medicolegal actions that radically changed the course of the patients lives, and which involved extrafamilial authorities to an uncomfortable extent for a large portion of the public. Studying the textual traces of the diagnosis process can help us understand how patients, caught in the mental health system (which in the nineteenth century was the insane asylum), struggled to assert their identity as individuals, provoking in the process debates about the meanings of normality, personhood, identity, and autonomy, to name a few critical topics. Such debates often spilled over into the public sphere via lawsuits, memoirs, newspaper editorials, essays in literary and legal magazines, legislative forums, and so on, forcing ongoing conversations on the issue of the definition, rights, and proper treatment of the mentally ill person.

Next page