REVELATIONS OF DIVINE LOVE

JULIAN OF NORWICH (c. 1342after 1416) is the first writer in English who can be certainly identified as a woman. Nothing is known of her background, not even her real name. On 8 May 1373, when seriously ill and apparently dying, she received an extraordinary series of showings or revelations from God, beginning when her parish priest held up a crucifix before her and she saw blood trickling down Christs face. After her recovery, she spent many years pondering the significance of the showings, which she believed to be messages to all Christians. They taught, among other things, that God is our mother as well as our father, that he cannot be angry with us and that no Christian will be damned doctrines which Julian had great difficulty in reconciling with the Churchs teachings. She wrote two accounts of the showings: an earlier, shorter version of Revelations of Divine Love and a later, longer version, in which we can recognize her development from a visionary into the most remarkable English theologian of her time. In later life she lived as an anchoress at St Julians Church, Norwich (from which she adopted the name by which she is known), and became famous as a spiritual adviser. This volume includes both versions of the Revelations. They are major works of religious devotion, of theology and of English literature; their beauty and originality have won them many modern admirers (including T. S. Eliot), and in recent years they have attracted special attention for their female authorship and their attribution of feminine characteristics to God.

ELIZABETH SPEARING holds a D.Phil. from the University of York. Her previous publications include an edition of The Life and Death of Mal Cutpurse and articles on the Amadis cycle and on Aphra Behn.

A. C. SPEARING is William R. Kenan Professor of English at the University of Virginia and a Fellow of Queens College, Cambridge. He has published numerous books and articles on medieval literature.

Elizabeth Spearing and A. C. Spearing have collaborated previously on editions of Chaucers Reeves Tale, Shakespeares The Tempest and an anthology Poetry of the Age of Chaucer. They live near Norwich.

JULIAN OF NORWICH

Revelations of Divine Love

(SHORT TEXT AND LONG TEXT)

Translated by ELIZABETH SPEARING

With an Introduction and Notes by A. C. SPEARING

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 182190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

This translation published in Penguin Classics 1998

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Translation copyright Elizabeth Spearing, 1998

Introduction and Notes A. C. Spearing, 1998

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the editors have been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

EISBN: 9780141904528

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Julian of Norwich and her Book

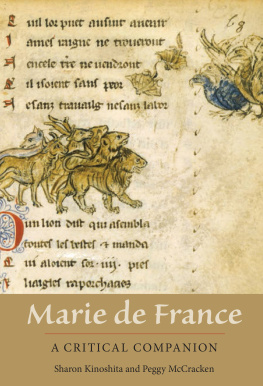

Julian of Norwich is the first writer in English who can be identified with certainty as a woman. Before her, a few works survive written by women in other languages used in England notable among them are the short romances and fables in French by the great twelfth-century poet Marie de France and, since a large proportion of writing in medieval English is anonymous, some of it may have been by women of whom nothing is now known. But most medieval Englishwomen were not educated or even literate, and those who were would not generally have been encouraged to write works intended to outlive some immediate purpose. Julians period, the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, is now recognized as one of the great ages of English literature the age of William Langland, John Gower, the Gawain-poet, Geoffrey Chaucer and his first major disciple Thomas Hoccleve in verse, and of Walter Hilton, Nicholas Love, the Wycliffite translators of the Bible and the anonymous writer of The Cloud of Unknowing in prose. These were all men, and it took some very unusual stimulus to impel a woman to write, and especially to write a work designed to teach others. What this stimulus was for Julian is revealed by the texts translated here the two versions of her Revelations of Divine Love, her only known writings, an earlier short version (ST) and a later long version (LT).

Julian states in LT that These revelations were shown to a simple, uneducated creature in the year of our Lord 1373, on the eighth day of May (chapter 2).

What Julian meant by describing herself as uneducated (that cowde no letter) has been much discussed. Some have argued that it indicates that she was illiterate, so that her writings must have been penned on her behalf by someone else, presumably a man. The concept of literacy Julian is manifestly a woman of exceptional intelligence, and she shows not just an understanding of theology, the province of learned male clerics, but a capacity for powerful new theological thought; moreover, her prose, while owing much to speech, is distinctive and distinguished. If she emphasizes her ignorance, describing herself as a woman, ignorant, weak and frail (ST chapter 6), this is likely to have been both out of genuine humility and so as to avoid her contemporaries unease with female learning, especially in theological matters. She may have had little or no Latin (to know no letter could well mean that) and nothing is known for certain of her reading, but there seems no reason to deny her authorship, in the fullest sense, of the work attributed to her.

Julian reveals little of her life, beyond certain details that authenticate her religious experiences. This reticence was evidently a matter of principle, and in LT she omits even some of the few personal items mentioned in ST. She urges her readers to concentrate on the revelation itself and stop paying attention to the poor being to whom [it] was shown (chapter 8), and later explains that, when she desired to know whether a certain friend would continue to lead a good life, she learned that it was not to Gods glory to be concerned about any particular thing (chapter 35; cf. ST chapter 16) hence the omission of nearly all such particulars from her writing. External documents but the details in ST of her circumstances in 1373 indicate a secular domestic setting: when she seemed about to die, her parish priest was sent for, he was accompanied by a boy, and later My mother, who was standing with others watching me, lifted her hand up to my face to close my eyes, for she thought I was already dead (ST chapter 10). Probably then Julian was at this time either an unmarried daughter living at home or a widow. The centrality of motherhood in her religious thought might suggest that she had been a mother herself. Later, presumably influenced by the showings, she adopted a fully religious mode of life, becoming not a nun but an anchorite.

Next page