For my niece, Sandra Winyard who always asked why

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I am eternally grateful to have been awarded several bursaries, for such a book, which demands years of research, is impossible to write without them. Profound thanks go to my colleagues at the Guild of Food Writers and to the Authors Foundation for their help; this book could not have been written but for them. Many thanks also to the British Library, the Wellcome Library, the London Library and to Mass-Observation at Sussex University Library for their time and patience; all material from the latter has been reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd., on behalf of the Trustees of the Mass-Observation Archive. I am deeply grateful to have had the enthusiasm and encouragement of my publisher, Anne Dolamore, throughout. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Ron Latham and the labour of love he has performed in picture research and also to his extensive library. I am thankful to Amy Myers for her rigorous editing and that rare ability to perform such a task with humanity and humour. I am also happy to thank friends and colleagues who were eager to help and enlighten, especially Dr Gary Lewis, Catherine Brown, Margaret Shaida, Prue Leith and Darina Allen on areas that were previously obscure to me. Lastly, my thanks to my partner, Claire Clifton, and her own library which has been indispensable.

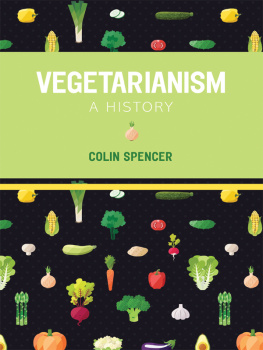

This new edition published 2011

by Grub Street,4 Rainham Close, London SW11 6SS

post@grubstreet.co.uk

www.grubstreet.co.uk

First published in hardback 2002 and reprinted 2003, and in paperback in 2004

Text copyright Colin Spencer 2002, 2011

Jacket design: Sarah Driver

Picture research: Ron Latham

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-908117-03-8

eISBN 9781908117779

Formatting by Pearl Graphics, Hemel Hempstead

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall

on FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) paper

Contents

Introduction

How did the mixture of peoples that became the British come to have such definitive culinary tastes? This, of course, is a question we can ask of all nations, but of the British we can also ask: why did their particular style of food decline so direly that it became a world-wide joke, and how is it now climbing back into eminence?

I first became excited by the history of British food when I read some of the earliest known Anglo-Norman recipes that have come to light only in the last 20 years, and realised not only how Lucullan early medieval food was (for that was to be expected with an oppressive, affluent elite intent on ritual and ceremonial), but how extraordinarily stylish, tasteful and contemporary the dishes were. This was food designed to please and satisfy very sophisticated palates, it was food that we would now consider to be the height of gourmet elegance. It was food full of exotic ingredients and Mediterranean influences, with spices and flavourings from all over the then civilised world. As the historian Christopher Hill wrote:

Each generation asks new questions of the past and finds new areas of sympathy as it re-lives different aspects of the experiences of its predecessors. obviously considered the recipes to be thoroughly unpleasant; what is more, not having worked out the amounts of spices per person, he seriously thought that an excessive amount was used and that this must be because they were necessary to mask rotting food. Thus began that particular canard which, though eminent historians since have considered it nonsense, has been difficult to destroy. When there is an amount given for a particular recipe which also states how many people it is meant to feed, the resulting flavour can be worked out; as readers will see on pages 50 and 80, the spices would have bequeathed a subtle sub-text to the finished dish and not overpowered it at all. My own view of this period is that Anglo-Norman cooking reached the heights of gastronomy, which it shared internationally with the courts of Europe, but that its cooking was influenced more by Persia (now Iran), as were the countries of the Mediterranean, than by Paris.

Because we all enjoy food, and there is little debate that it is one of the greatest delights in life, my view about what we ate in the past is a simple one. I think the food of the past was just as delicious as the food of the present. I dont believe people who have any choice in the matter bother to eat gunk. Because of poverty, the majority of people throughout our history were reduced to a very small range of subsistence foods; because all they had to eat was bland and monotonous, they searched for ways to brighten it up into something greatly more appetising. They did that because thats what people are like now and people do not change. Human beings in the past were basically ourselves, driven by the same needs, hopes and desires; though born at a different time and given a different set of cultural influences, notions and beliefs, the palate as a sensual receptor had the same requirements as today, to be satisfied and stimulated.

So I differ from many food historians who have written disparagingly about the food of the past, either considering it gross, such as roasting whole carcasses which they ate till the fat ran down their chins and into their beards, which subscribes to a Hollywood view of the banquet as orgiastic pigswill; or, as I have mentioned above, as rotting meats which only a ton of spices could make palatable. There were hundreds of bye-laws which were used to prosecute cooks and butchers if they were discovered attempting to sell rotting food. Such erroneous impressions also ignore the fact that large carcasses were valued as live creatures which were labouring hard in the fields. You did not slaughter them until they were too old to work. Nor, as meat was so precious, did you cook them without great care and skill. Besides, the wide variety of recipes for sauces to have with different meats would delight any gastronome of whatever era and must surely impress us with the culinary expertise of the medieval cook.

Throughout the period of the first part of this book there were ceaseless struggles between the princes, the church and the nobility for their share and control in the produce of the land. In the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries a further group emerges: the privileged town-dwellers, the traders who were to become the bourgeoisie. In England they played a particularly influential role at an early date on our food and cooking. Food was to play a part as a visible celebration of power and affluence in the struggle between the various elites, and food was also the source if not an integral part of the wealth of the new bourgeoisie. When the sumptuary laws began and stopped tells us much about bourgeois affluence and pretension. See, for instance, page 49 on the spicers in the City of London in the twelfth century under Henry II. These traders provide an important clue to how much the new Anglo-Norman nobility treasured the use of spices in their cooking, which meant how much they cared about the flavour and the recipes. Fashion is also a guide: in ages where male courtiers were concerned about the length of hems, shoes and hair, that same aesthetic selectiveness operated at the table. It is unimaginable that such an immaculate and perfumed society sat down to eat coarsely while the fat ran down their chins.