Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FIRST PLATE SECTION

SECOND PLATE SECTION

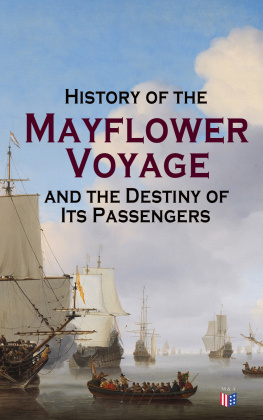

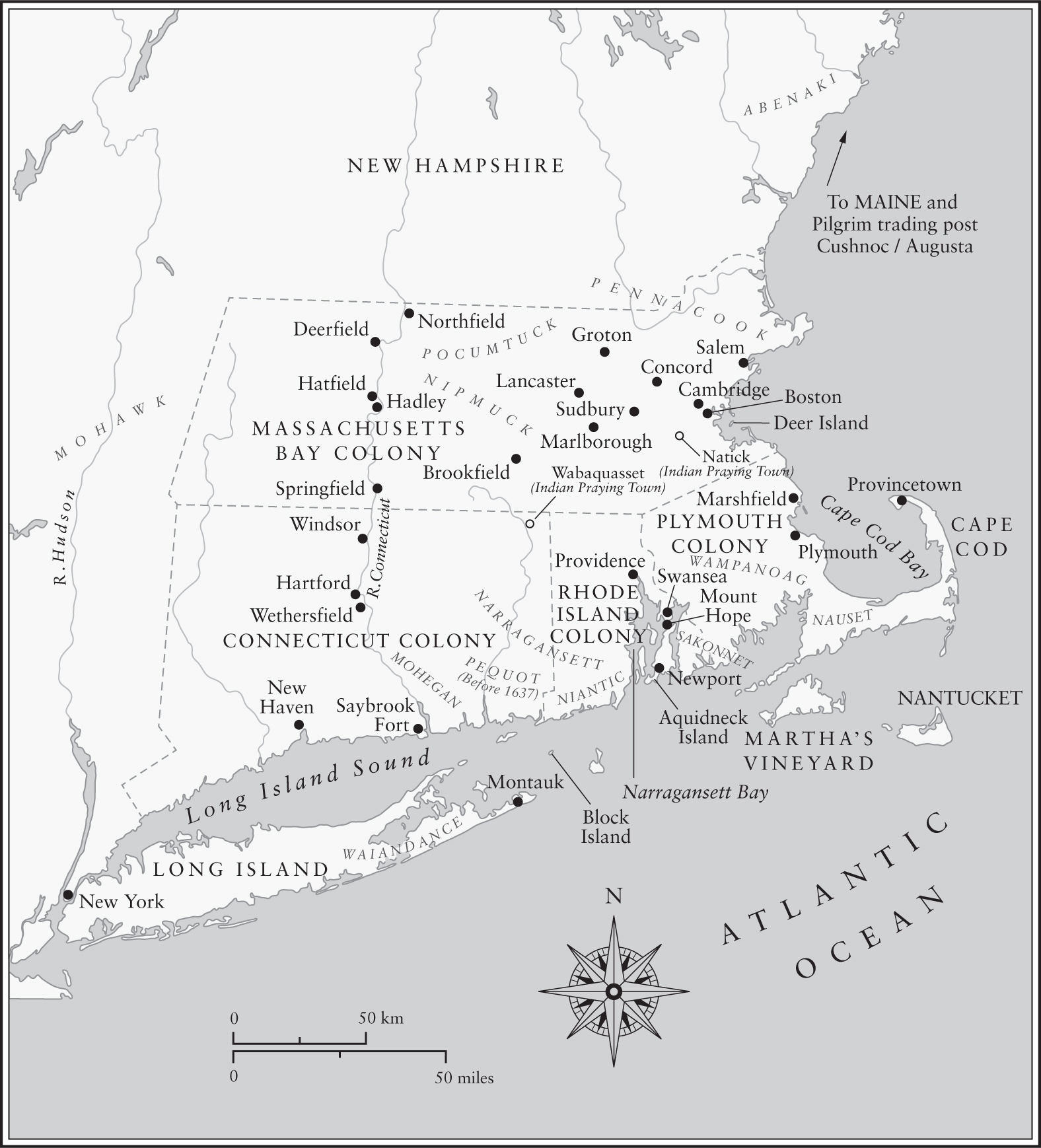

A simplified map of the colonies of 17th century North America

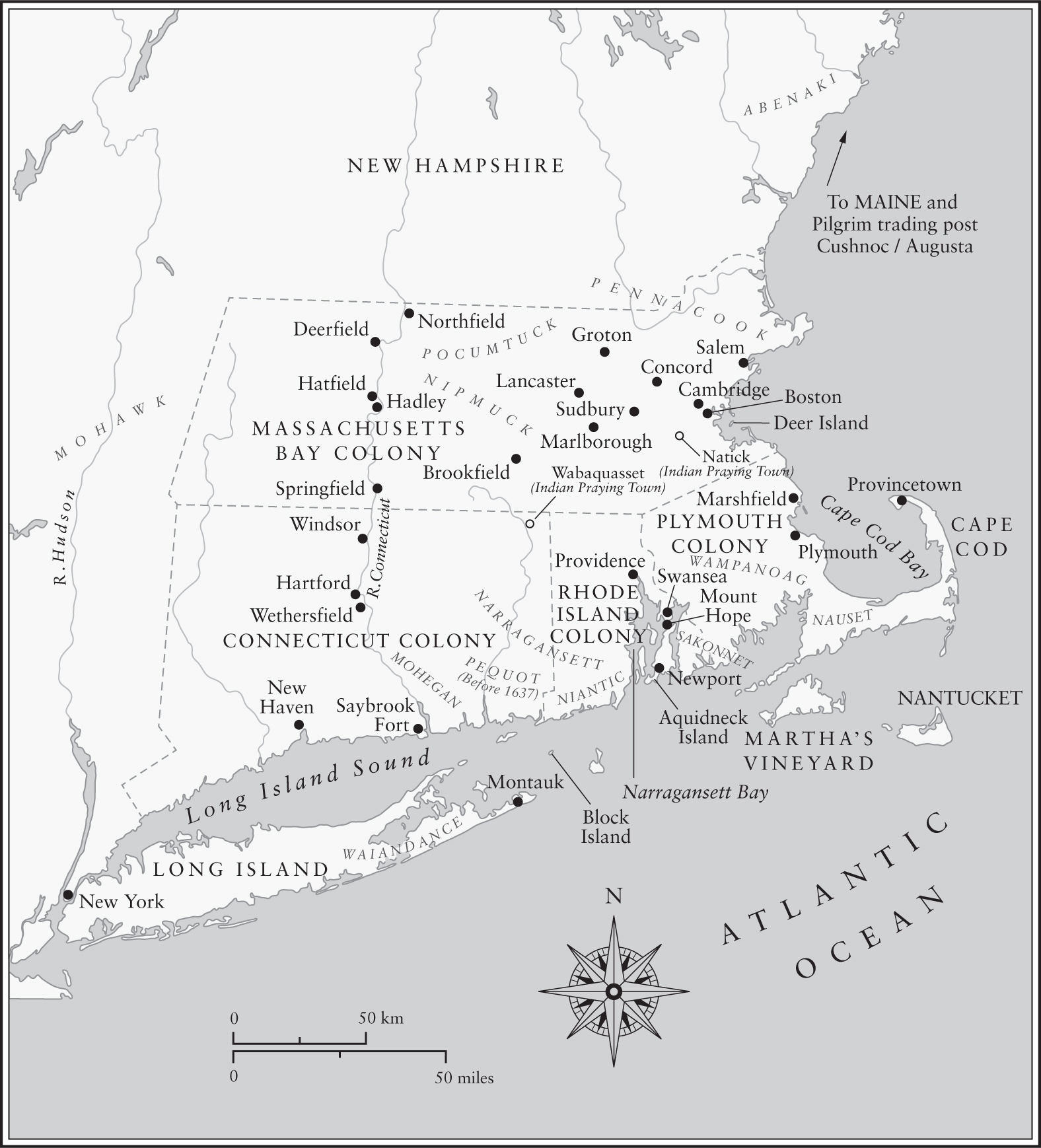

A simplified map of southern New England in 1675, before King Philips War, showing English settlements and American Indian tribes

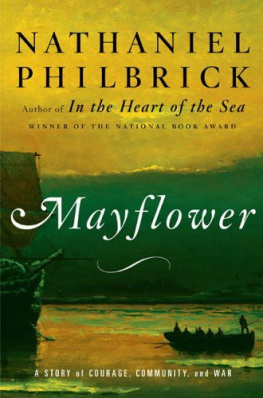

On 12 August 1676 as dawn revealed the dark pine trees and low shores of Rhode Island, the rising sun also lit up the dome-shaped rock called Mount Hope. From the ledge where his men had pitched camp for the night, the chief of the Wampanoag tribe, whom the English called King Philip, looked down and prepared to flee. He and his braves were completely surrounded by English soldiers.

Sixty years earlier, before the coming of the Mayflower , Philips fathers land stretched to Cape Cod. But by 1676 Mount Hope was his sons last remaining stronghold.

The Indians had been so successful at evading the English that Philip was convinced they were secure in this most secret home territory. He had not bargained for the tracking skills of Colonel Benjamin Church, the commander of the English, who was using Indian scouts to supplement the colonists woodcraft. Philip had escaped too often, and Church was determined to trap him. In the duel of wits that had been going on for the past month, Church made careful mental notes of Philips way of operating. One of Philips men going out to relieve himself in the early morning had been shot at. Now gunfire was ricocheting wildly up the rock.

As the Indians returned fire, Philip threw off his meal satchel, cloak, jewellery and powder horn, which would weigh him down. Gun in hand, he started to leap through the wood into the swamp. The English were wary of swamps because they were so difficult to navigate. Philip had a good chance of escaping through its dark recesses as he had in the past.

Perhaps, though, he no longer cared very much what became of him. The fight had gone out of him after the English had caught his wife and treasured nine-year-old son. Clergymen in Boston were now debating bringing biblical precedent to bear on whether it was right to hang this boy the child of a rebel or sell him into slavery.

There was nothing in the annals of family history to suggest that Edward Winslow, and eventually his younger brothers, would migrate to live in a religious colony 3,000 miles away. Everything about his early life seemed comprehensively tied down by the entangling webs of tradition and desire for worldly position. His father, also called Edward, was an aspiring merchant, in the prosperous Midlands market town of Droitwich.

Edward senior dealt in grain and pease, had an interest in the salt business and travelled for work, mainly to Bristol, sometimes to London for a court case or to hand over clients monies. He was in effect a paralegal, or legal executive someone with a knowledge of the law but not sufficiently well educated to have been qualified and seems to have been an unofficial notary or person of standing in the community who could be relied on for witnessing legal documents.

He mingled with the elite who ran the town. Though regarded as a decent and reliable chap, he was not quite one of them. He and his wife Magdalen were always scraping by, though she was of gentle birth and the Winslows themselves had seen better days. To her chagrin he never owned his own house. They moved home several times over twenty-five years. Sometimes they lived pleasantly in the sort of cosy sixteenth-century salt merchants house which today is still seen in Droitwich High Street; at other times, as business waned they found themselves in smaller, damper lodgings.

Edward and Magdalen Winslows eldest child was christened Edward on 20 October 1595 over the medieval font in the ancient church of St Peter in Droitwich. They went on to have four more sons John, Gilbert, Josiah and Kenelm and a daughter, Magdalen.

For several hundred years the Winslows had been recorded as living in Worcestershire as yeomen farmers. But at the end of the sixteenth century Edward seniors father, Kenelm Winslow, decided to stop being a yeoman farmer getting by on seventy-five acres, and became a cloth merchant.

There has been much debate about the Winslows social status. In the more class-ridden age of the nineteenth century, rumours proliferated that they were of aristocratic descent. They themselves, however, were proud to use the term yeomen, which is what we would call middle class.

Yeomen could be wealthy enough to move amongst the gentry, and a reference in a seventeenth-century history of Worcestershire suggests that at some point Kenelm was a man of considerable estate, but then fell on hard times. However, it is generally agreed among historians that he owned a large house at Kerswell Green. Today it is a Grade II listed building, a thatch-roofed farmhouse from the late medieval period, with various alterations in the seventeenth, eighteenth and twentieth centuries a fairly extensive half-timbered house with a large hall, gables and expensive brick elements.

Judging by the inventory attached to his will, Kenelm was a man who was accustomed to the elegances of the sixteenth century: he had table linen and napkins, and drank out of glasses. His meals were cooked in brass pans and served in brass pots and pewter dishes.

Kenelm was a daring and perhaps rather too entrepreneurial type, a trait his grandson Edward junior would inherit. Becoming a clothier or cloth merchant was one of the swiftest means to wealth during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Worcester and Droitwich were boom towns because of the cloth industry. Ever since the Roman occupation, Droitwichs position on massive salt deposits made it prosperous. As well as being the best preservative for fish and meat before refrigerators, in the late Middle Ages salts chemical properties became integral to the cloth trade, and Droitwich really took off. Salt was not only used for cleaning, dyeing and softening wool and leather but the trade also expanded into materials used in shipbuilding, such as flax and hemp, as well as medicines and ointments. A tradition of commerce and centuries of busy, crafty merchant activity and lucrative trade meant Droitwich was notably successful. And its propinquity to Worcester had a knock-on effect.

Worcester was famous for its rich red dye and was a centre for the international wool trade. Merchants in the late sixteenth century were the new success story. They were flexing their muscles, feeling their strength. Famously termed the middle sort of people, they were a composite body of people of intermediate wealth, comprising substantial commercial farmers, prosperous manufacturers, independent tradesmen and the increasing numbers who gained their livings in commerce, the law and the provision of other professional services. Kenelm Winslow and his son Edward now had their feet fairly well set on the first rungs of this dynamic merchant community . It was the place to be.