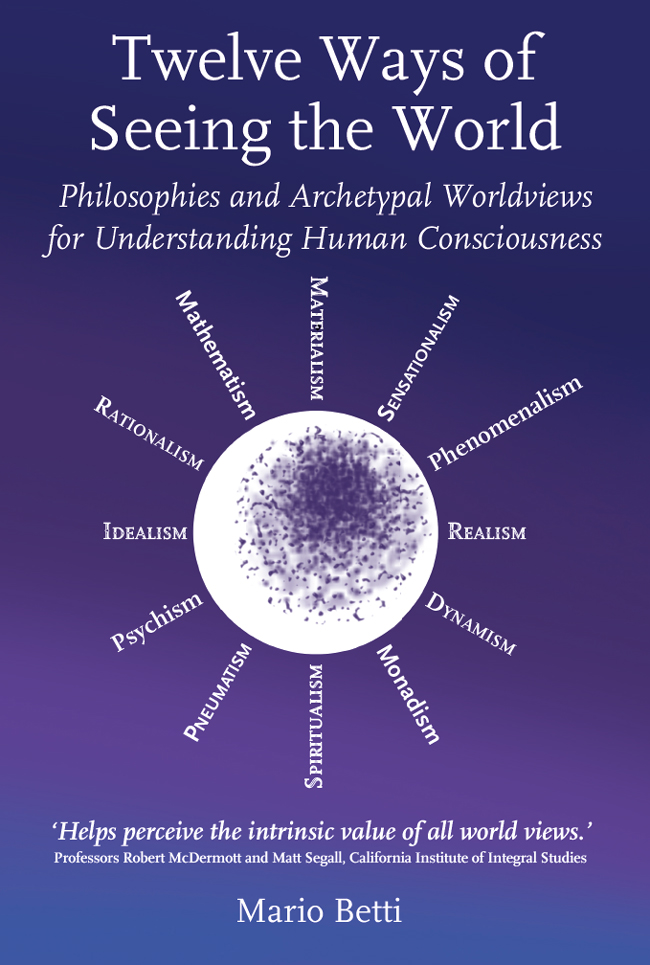

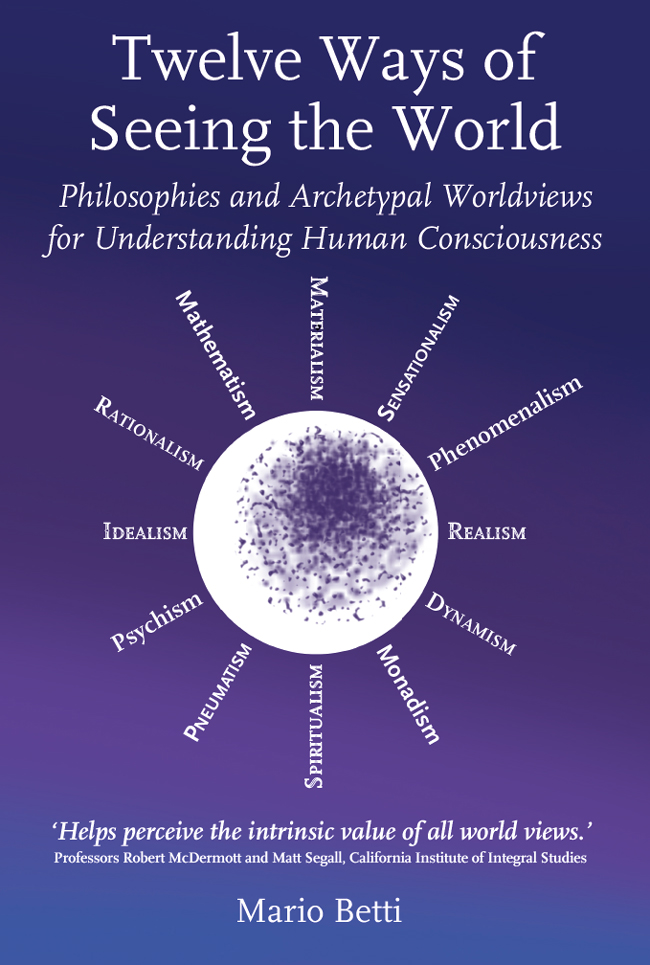

TWELVE WAYS OF

SEEING THE WORLD

PHILOSOPHIES AND ARCHETYPAL

WORLDVIEWS FOR UNDERSTANDING

HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS

Mario Betti

Translated by Matthew Barton

Zwolf Wege, die Welt zu Verstehen 2001 Mario Betti

Mario Betti is hereby identified as the author of this work in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. He asserts and gives notice of his moral right under this Act.

Twelve Ways of Seeing the World was first published as Zwolf Wege, die Welt zu Verstehen, in 2001 Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart, Germany.

Twelve Ways of Seeing the World 2019 Hawthorn Press.

Published as an English edition by Hawthorn Press, Hawthorn House, 1 Lansdown Lane, Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 1BJ, UK

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means (electronic or mechanical, through reprography, digital transmission, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover design by Lucy Guenot

Typesetting in Minion Pro by Mach 3 Solutions Ltd (www.mach3solutions.co.uk)

Translation by Matthew Barton

Printed by Severnprint Ltd, Gloucestershire

Every effort has been made to trace the ownership of all copyrighted material. If any omission has been made, please bring this to the publishers attention so that proper acknowledgement may be given in future editions.

The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher.

Acknowledgement: Hawthorn Press acknowledges the generous support of The Cloverleaf Foundation, www.cloverleaffoundation.com, which made the translation of Twelve Ways of Seeing the World possible.

Printed on environmentally friendly chlorine-free paper sourced from renewable forest stock.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978-1-912480-12-8

eISBN 978-1-912480-22-7

Twelve Ways of Seeing the World

In todays multicultural society, religious and philosophical outlooks of all kinds often seem to clash irreconcilably. Mario Betti is concerned to see the validity in each worldview, and to seek truth not in one narrow perspective but in the overall context of all the possible different outlooks. In clear, accessible language, he helps readers engage with twelve perspectives on the world, at the same time offering insight into anthroposophy, and new understandings of it.

Mario Betti was born in Lucca, Italy, in 1942. Following studies and work in Italy, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and England, he settled in Germany. He studied Waldorf pedagogy and subsequently worked for many years as a teacher of English, history, history of art and religion. From 1985 to 2001 he was a lecturer in pedagogical anthropology, history of art and anthroposophy at Alanus University, Alfter, near Bonn, and was an art teaching advisor to Waldorf schools. From 2001 to 2006 he was a lecturer at the Waldorf teacher training course in Stuttgart. Mario has published various books on literature and spiritual science.

Four blind men are trying to decide what an elephant is.

They each feel and touch the elephant, clearly a patient creature, and thereupon each gives his view:

A pipe, says the first, touching the trunk.

A wall, says the second, feeling its side.

A whip, says the third, feeling its tail.

A tree, says the fourth, who has got hold of a leg.

Old legend

Contents

Foreword

Robert McDermott and Matthew T. Segall

Rudolf Steiner was one of the twentieth centurys few true Renaissance men. While modern science, art, religion, politics and philosophy continued to fall into increasing specialisation, fragmentation, deconstruction and narrow-minded conflict, Steiner laboured tirelessly to create new integral approaches to education, agriculture, medicine, architecture, social reform, banking, visual and performance art, esotericism and more all inspired by a deep commitment to humanitys spiritual potential. Mario Betti, a lifelong practitioner of Steiners anthroposophical method, has written a book that succeeds not only in its clear interpretation of a sometimes enigmatic thinkers ideas, but in its brilliant amplifications and applications of these ideas to our present-day circumstances.

Betti offers his book as a stimulus or seed to support the growth of a still-fledgling pluralistic society. Achieving a planetary humanity guided by freedom and love out of the ashes of the modern pathologies of fascism, totalitarianism, nationalism, oligarchism and terrorism (the list goes on) will require more than a shallow, relativistic multiculturalism that settles for mere tolerance. Betti draws on Goethe to remind us that tolerance can only be a temporary position. Genuine pluralism, Betti demonstrates, requires more than toleration: it requires a willingness to engage the whole of our being in deep communication with, and mutual affirmation of, other worldviews. We must strive to reach across our differences through an inner development that is capable of seeing their holistic interdependence. Bettis amplification of Steiners twelve worldviews is a profound aid in this effort of inner development. Significantly, it shows the dignity and merit of each way of seeing the world at the same time as revealing the danger of exclusivism. Every worldview becomes false, the moment it claims to be the whole of the world.

Albert William Levys Philosophy and the Modern World, a particularly expert and readable account of twentieth-century philosophies, summarises our present situation well:

philosophical movements of the recent past are to be viewed as waves of successive reform beating upon an infinite shore, with each group of partisans committed to a conception of philosophy which assures them a virtual monopoly of its legitimate practice. And to pragmatists, logical empiricists, and linguistic analysts alike, any alternative conception of what philosophy is rests upon a tragic mistake.

Who would dare an attempt to overcome such differences of opinion, each supported by knowledge and powerful arguments? An ideal candidate would be a teacher whose thinking is lifted by creative pedagogy and artistic imagination. Mario Betti would appear to be such a teacher. Every page of this book reveals an author who teaches thinking as a contribution to individual lives, to relationships and to a sane society. He is invested not in scoring philosophical points but rather in helping his readers cope with intellectual confusion and conflict.

Betti succeeds in his purpose by giving a positive account of twelve worldviews. He takes as his model Goethe, who held in one view both universal harmony and plurality (). We are led to appreciate that each worldview is convincing up to a point. His treatment of Idealism, for example, invites the reader to see that all reality is, or at least emerges from, ideas from a realm that Plato described so convincingly. But then Betti draws on Aristotle, an equally brilliant and equally influential philosopher, to show the need for a more positive account of particulars, whether moments, thoughts or objects. Betti refers to this combination of Platos and Aristotles philosophy as Realism, the philosophy that occupies the top-most spot on the philosophical compass (more on this below).

In a similar way the way of showing polarities Betti makes a case for Rationalism, the philosophy of ethical order and proportion, and then shows how it virtually solicits its polar complement, the philosophy of Dynamism: structure needs process to be effective; and process, in order to avoid chaos, needs structure. As an introvert needs at least a little extroversion to get through the day, and as melancholic and phlegmatic temperaments need at least a touch of choleric and sanguine temperaments, so does Psychism, a philosophy ready-made for psychology, need a little Phenomenalism, a philosophy that emphasizes the reality of external ).

Next page

![Mario Vargas Llosa [Mario Vargas Llosa] - Captain Pantoja and the Special Service](/uploads/posts/book/142220/thumbs/mario-vargas-llosa-mario-vargas-llosa-captain.jpg)