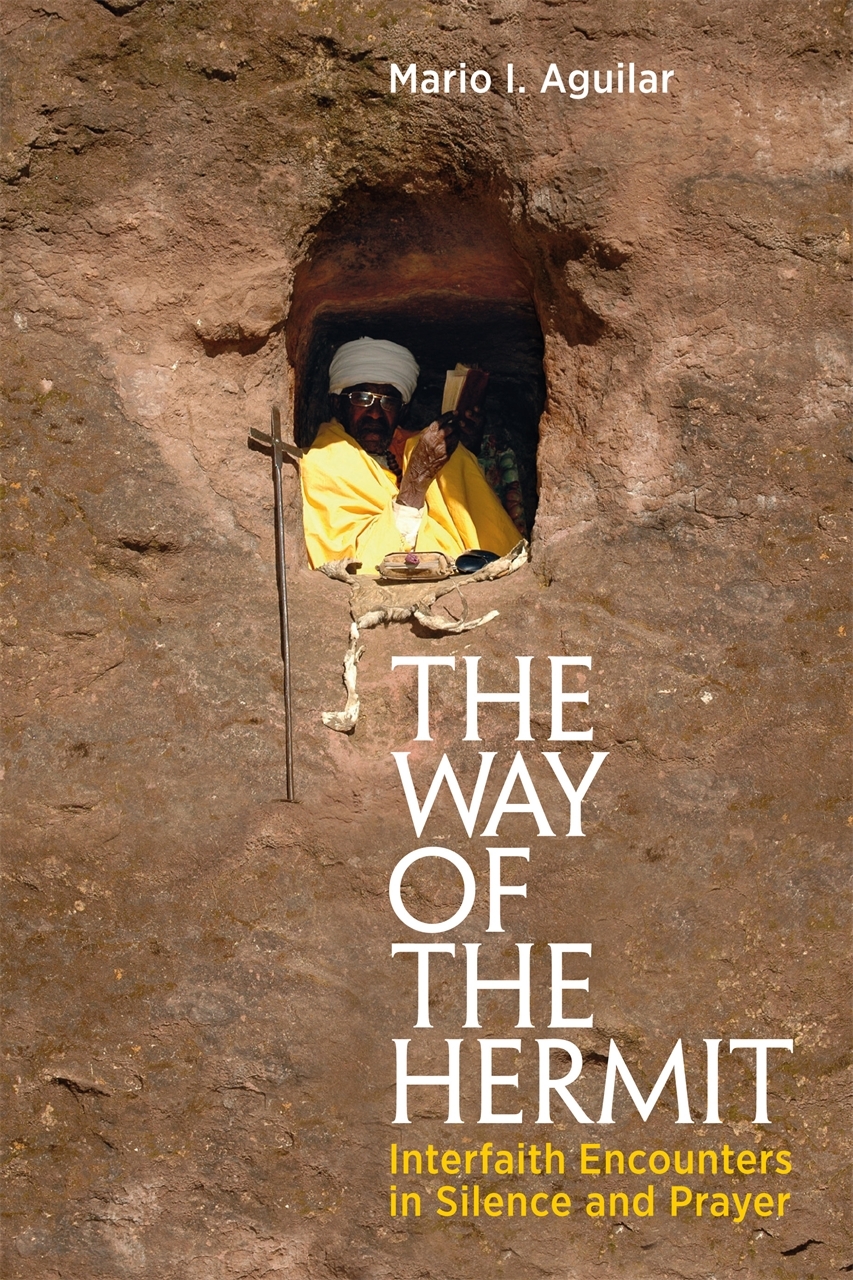

THE

WAY

OF

THE

HERMIT

Interfaith Encounters in

Silence and Prayer

Mario I. Aguilar

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Dedicated to the memory of

Roberto Tello Verdejo (+2016)

To his daughter, Glenda Tello

To Sara Ann Catherine

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

Experiencing Contemplation and Interfaith Dialogue

The way of a hermit is the way of a Christian who has sought his journey with God through the centrality of space contained in a single monastic cell in which his or her life connects with the passing of time. The cell as the locality of the spiritual journey is located outside a monastery, on a hill, inside a cave, beside a beach, or even within an apartment in an urban centre. Time becomes the reality in which God and the hermit meet and in which the hermit and others meet. Minutes, hours, days and years of such eremitic life relate to one individuals search for God and for an ongoing conversation with God in solitude and a daily encounter with other human beings, sentient beings and the whole of creation. However, hermits, because of their way of life seeking holiness and enlightenment, have always attracted other pilgrims who have come closer to a hermitage to seek prayers, encouragement and spiritual affirmation. Thus, in the case of Charles de Foucauld, Abhishiktananda, Thomas Merton and even Mahatma Gandhi, the solitude sought and the renunciation practised led eventually to encounters with others, not only through the challenging of a world around them but in a deep conversation and encounter with practitioners of other faiths and other philosophical systems. Such solitude has been marked by what I have called in my previous work on ChristianHindu dialogue dialogues in history, whereby dialogue is an Therefore, in this work I explore that eremitic characteristic: a solitude and search for spiritual and self-development that brings unto it the encounter with others and the search for others experiences of the Absolute.

In contemporary times, hermits have also been part of a monastery or a religious community, and within such communal experience they have chosen to spend time alone near their monastery. Thus, that monastic experience of solitude, such as that experienced by Thomas Merton in his house/hermitage at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, has still been located within the principle of stability and monastic obedience (and therefore of authority) of the cenobium . It is a fact that monastic cenobitic communities such as the Benedictines and the Cistercians have centred their contemplative life in a cenobium, a community of monks who share a common purpose, a common rule and a communal liturgical life, with a vow of stability and attachment to a particular community, abbey or monastery. Arising out of those monastic communities, and since the beginnings of the Church, there have been Christians that have sought God through personal solitude, with the example of the Fathers of the Desert as the most influential within the history of the Christian Church. However, the most well-known Christian hermits of the twentieth century were those who slowly moved from personal solitude attached to a community to personal solitude and attachment to others outside their initial experience of the cenobium. Those who lived such experience include Charles de Foucauld (North Africa), Henri Le Saux (India) and Thomas Merton (United States), who also shared their deep search for an experiential encounter with other religious and philosophical traditions.

EREMITIC LIFE AND INTERFAITH DIALOGUE

This sitting in ones cell becomes the first place where the hermit converses with the God of many peoples and many faiths and learns to leave attachments and prejudices behind. In the interpretation by Robert Hale, solitary contemplation is that moment of entering into deepest koinonia and love with the ineffable God, to seek to fulfil more perfectly that first part of our Lords commandment of love, to love God with our whole heart, mind, soul, strength.

A young Sikh who had already attended prayers in the morning brought me to the temple. Shoes were left with an attendant, washing of the body took place, the head was covered, and my life companion and I joined hundreds of people who were descending on the carpets where pilgrims walked under the midday sun. We kissed the ground where sacred stones pointed to the Sikh memory of holy men, and we prayed together with those who were bathing under the sun. There were literally hundreds of people who went around praying, listening to music and drinking water while others were resting on the floor. Musicians were playing music, and holy men were reading scriptures and blessing pilgrims; however, I felt very much that this was my experience, an individual experience of togetherness with many others. There was no need for words or narratives as our feet were burning on the hot ground and the end of my trousers became wet with the water that surrounded our walk.

There was no return from the movement that had started at my hermitage and that for unknown reasons had brought me and my life companion to Sri Harimandir Sahib. However, the knowledge we had acquired of Sri Harimandir Sahib had been experiential, and the togetherness of faith had been of silence and closeness. I had experienced the sacred space of the Sikhs, and in doing so I had been able to meet Sikhs by having some ritual experience in common. It is a fact I have visited many temples and many sacred places in my life, and each one of those experiences of the divine have changed my perception of other faiths and other pilgrims. Those from other faiths who have visited my hermitage have also experienced such changes in perception and in experience. Thus, once an individual has entered the cell and has committed hours to contemplation and prayer, there is no return because the possibility of experiencing God is all-encompassing as well as challenging and terrifying. The experience of places of prayer and devotion are common to all humanity, and in experiencing such moments we come together in a manner that is simple and human. After such encounters, we cannot return to the distrust of other faiths, because we have experienced a glimpse of the unity of the divine reality. We have been transformed beyond recognition into members of humanity without the occupational levels that divide us into caste, class and race.

I recognize that to explain such a journey from isolated prayer into a human togetherness with others requires a language that is closer to poetry and art rather than to reasonable propositions and textual exchanges. In many ways, it is the imagination that allows the human mind to foresee paths and ways which were not explored previously. I am very much

I offer within this work my own experience of an eremitic life that has brought me into deep communion with pilgrims of other faiths, sometimes through silence and the sharing of experiences, at other times through the mediation of a dividing space through virtual reality. It offers glimpses of an eremitic attempt to become one not only with Christians but with all other pilgrims, especially Hindus and Buddhists. some of these conversations and silences and my own road to silence. For it is through the sound of silence that interfaith dialogue starts and continues.

Language becomes a problem because this togetherness in prayer and contemplation, in togetherness and silence, requires the language of the heart, the language of a contemplative and mystical theology that does not find an adequate language of expression within the daily language of commerce, work and the markets. These difficulties are usually manifested in the honest and kind questions of others who ask me what I do, to which it is easy to reply: I pray. However, beyond that answer and the subsequent conversation, it is difficult to convey that prayer and contemplation in silence are not an occupation but a journey of love with God and with others. Thus, once I have spent time with God, I want to meet those who are praying within other religious traditions to pray with them, to kneel on the floor while they prostrate or stand. Ultimately, and as a result of this diverse prayer in a shared space, I feel an enormous love, devotion and responsibility for them. The commandment love thy neighbour does not only extend to alms and charitable work but also to our love for others whom we dont know, who dont share our way of life, our ideas and aspirations, and who have a different philosophical or symbolic system of understanding their lives and their journeys.

Next page