GODS

PEOPLES

COVENANT AND LAND IN SOUTH AFRICA, ISRAEL, AND ULSTER

Donald Harman Akenson

CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS

ITHACA AND LONDON

Copyright 1992 by Donald Harman Akenson

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, 124 Roberts Place, Ithaca, New York 14850.

First published 1992 by Cornell University Press

Printed in the United States of America

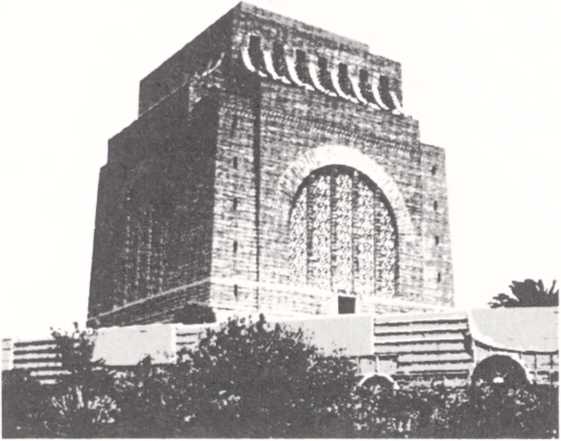

Art on part opening pages: Voortrekker Monument, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa.

The paper in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Akenson, Donald H.

Gods peoples : covenant and land in South Africa, Israel, and Ulster I Donald Harman Akenson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8014-2755-X (alk. paper)

1. Covenants (Religion) 2. South AfricaCivilization.

3. Afrikaners. 4. IsraelCivilization. 5. Ulster (Northern

Ireland and Ireland)Civilization. I. Title.

BL617.A44 1992

231.7'6----dc20 92-8758

In memory of my father Donald Nels Akenson 1910-1990

Contents

Maps and Figures ix

Acknowledgments xi

Part I THE ADAMANTINE WORD

1. The Oldest Code 3

2. A Very Big Deal

Part II COVENANTAL CULTURES IN THE MAKING

3. The Afrikaners: A Culture in Exile, 1806-1948

4. The Covenantal Culture of the Ulster-Scots to 1920 97

5. Zionism and the Land of Israel to 1948

Part III THE COVENANT AND THE STATE

6. Northern Ireland: A Protestant State for a Protestant People, 1920-1969

7. The High Noon of Apartheid, 1948-1969

8. Israel: A Singular State, 1948-1967 227

viii Contents

Part IV THE COVENANT IN RECENT TIMES

9. A Covenant Comes Apart: Ulster, 1969 to the Present

10. A World Unhinged: Afrikaners and Apartheid, 1969 to the Present 295

11. Israel, 1967 to the Present: Completing the Circle

Part V ENVOI

Notes

Index

Maps and Figures

MAPS

1. Africa, 1914

2. Irish counties

3. The Ulster plantation

4. Irish religious proportions, 1834

The British mandate

South Africa, 1985

7. Israel, 1947, 1949, and 1967

FIGURES

ix

Acknowledgments

For direct support in writing and publishing this book, 1 am grateful to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada; the School of Graduate Studies and Research, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario; the Stout Research Centre of Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand; the Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa; and the Jackman Foundation.

Scores of scholars in South Africa, Israel, and Ireland, as well as in Canada, Great Britain, and the United States have been generous with their time and knowledge. Because this is a controversial volume, 1 shall not name them individually; I am grateful nonetheless.

D. H. A.

Part I

THE

ADAMANTINE WORD

The Oldest Code

(i)

Any careful reader of the Bible realizes that, often, stones speak louder than words. I had read a good deal about Ulster, and about South Africa, and about Israel, and I had faith in the fundamental accuracy, if read judiciously, of the historical record of each country. At a distant intellectual level I realized that these three culturesthe Afrikaner, the Ulster-Scot, and the Israelihad many things in common. But it was a flat, two-dimensional recognition.

Then 1 visited the Voortrekker monument in Pretoria, South Africa. It is an extraordinary structure, not only a monument to a cultures past but also a map of a collective mind. The monument is a national museum for the Afrikaners, but it could just as well serve as a defensive outpost. Its walls are as thick as were some parts of the Maginot Line, and it has sally ports and ambushments that would do credit to a medieval fortress. Each salient protects another.

What struck me was that I had encountered the mind that built this structure before, and in far distant countries. Although built in different eras and using sharply different technologies, the bawns of the Ulster-Scots, fortified farmhouses designed to protect against the indigenous Catholics, and the military-agricultural encampments of Israeli pioneers on the West Bank of the Jordan, hunkered down amid the Palestinian Arab population, came from the same cast of mind: the creation of 3

an interlocking defensive structure that asserted at once its own existence and the ability of those inside the structure to defend themselves against the alien and hostile outside world.

Later I realized that many of my friends and acquaintances in these three societies often spoke the same way, even though they used different languagesnot everyone, not all the time, but frequently enough to make me recognize that Northern Irelands Presbyterians, the Afrikaners, and most Israelis have held in common several fundamental concepts. This kind of observation intrigues a historian, and immediately I began to look backward. It soon became clear that the Afrikaners of the seventeenth through early twentieth centuries (usually called "Boers in contemporary usage) and the Ulster Presbyterians of the same era had been even more alike ideologically in those years than they are today. What they had in common was their understanding of how the world worked. And that understanding stemmed directly from the Hebrew scriptures.

Dan Jacobson, the son of Jewish immigrants to South Africa and himself the author of a lucid literary commentary on the scriptures, recalled of his own childhood:

I had as one group among my neighbors yet another chosen people: the Boers, or Afrikaners. Their national or collective myth about themselves owed almost everything to the Bible. Like the Israelites, and their fellow Calvinists in New England, they believed that they had been called by their God to wander through the wilderness, to meet and defeat the heathen, and to occupy a promised land on his behalf. How literally they took this parallel may be gauged from the fact that the holiest day of their national calendar bore the name Day of the Covenant. A sense of their having been summoned by divine decree to perform an ineluctable historical duty has never left the Boers, and has contributed to both their strength and their weakness.1

Anyone acquainted with the Irish Troubles of the twentieth century will quickly note the word covenant, for it is to one such covenant that the government of Northern Ireland owes its existence. On 23 September 1912, more than 218,000 menvirtually the entire adult male Protestant population of Ulstersigned Ulsters Solemn League and Covenant. This Ulster covenant was modeled on a Scottish Presbyterian original of the late sixteenth century which, in its turn, took its doctrine of the reciprocal responsibilities of God and a righteous civil polity directly from the Hebrew scriptures.