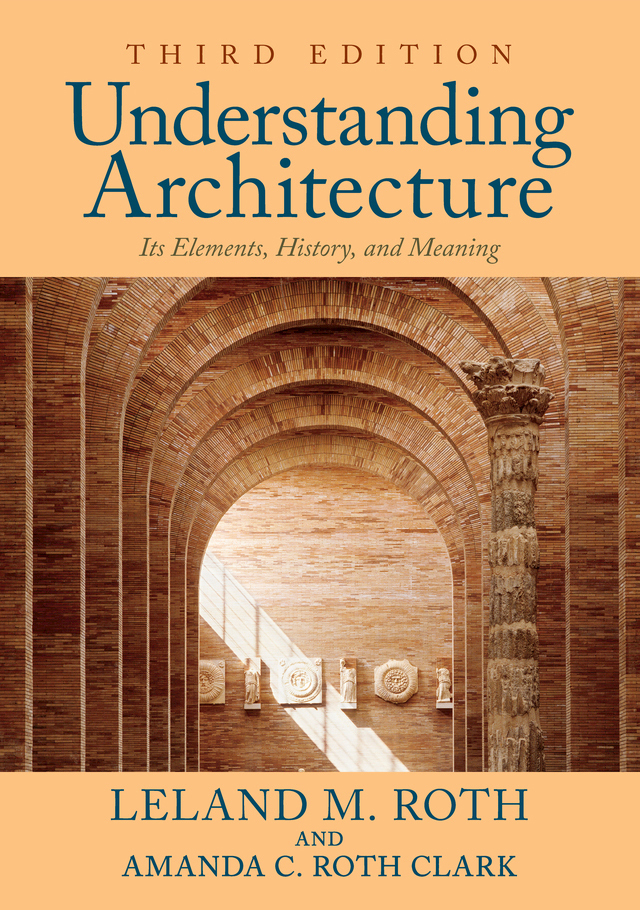

Understanding Architecture

Louis I. Kahn, The Phillips Exeter Library, Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, 19651971. A good example of what Louis Kahn meant when he said architecture is what nature cannot make. Photo: Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Understanding Architecture

Its Elements, History, and Meaning

THIRD EDITION

Leland M. Roth

and

Amanda C. Roth Clark

First published 2014 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2014 by Leland M. Roth and Amanda C. Roth Clark

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Every effort has been made to secure required permissions for all text, images, maps, and other art reprinted in this volume.

Design and composition by Trish Wilkinson

Set in 9.5-point Goudy Old Style

Photo research by Sue Howard

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roth, Leland M.

Understanding architecture: its elements, history, and meaning / Leland M. Roth and

Amanda C. Roth Clark.Third edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8133-4903-9 (pbk.)

1. Architecture. 2. ArchitectureHistory. 1. Title.

NA2500.R68 2013

720.9dc23 2013028188

ISBN 13: 9780813349039 (pbk)

Contents

Guide

Louis I. Kahn, The Phillips Exeter Library, Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire, 1965-1971.

Photo: Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. |

Part I

The Elements of Architecture |

Part II

The History and Meaning of Architecture |

This book is about learning to understand our human-made environment. It is about architecture as a physical vessel, a container of human activity. But since architecture is a social activity, building is also a social statement and the creation of a cultural legacy. Moreover, every building, whether a commanding public structure or a private shelterwhether a cathedral or a bicycle shedis constructed in accordance with the laws of physics in ways that crystallize the cultural values of its builders. This book is an introduction to the artistic urge that impels humans to build, as well as to the structural properties that enable buildings to stand up. It is also an introduction to the silent cultural language that every building expresses. This book, then, might be thought of as a primer for visual environmental literacy.

I should clarify that this is not a history of architecture in the normal sense of the word. There is historical information in the second part of the book, but the first part focuses on how the aesthetics of architecture influence our perception.

The first edition of Understanding Architecture was published in 1993, and numerous additions were made in 2005 for the second edition. In this third edition, the material is brought up to date, including developments since the opening of the new millennium. This restructuring, however, necessitated rethinking how to tell the story of twentieth-century architecture. Hence, there are now revised chapters on the development of Modernism: how it was defined in Europe in the first third of the twentieth century, then how it was exported around the globe in the second third of the century, and, finally, how reactions to Modernism proliferated and have diverged in the last third of the century and have continued into the opening of the twenty-first century. Up to the mid-twentieth century, architects tended to work primarily in their native countries, aside from those who were obliged by political or religious persecution to flee their homelands and seek refuge elsewhere, such as Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and Erich Mendelsohn.

Discussion of this late-twentieth-century international dimension to contemporary architectural practice has brought into focus the realization that global cultural influences have been in effect for more than twenty-five hundred yearsa period in which early trade and exploration brought various parts of the world together. As it seems appropriate to examine these global interactions and the architecture outside of the Western world, we have interspersed the main text with special essays that sketch how other cultures first began to interact with Western culture. And just as the original chapters with their Western focus never aimed to examine the full breadth of architectural history, even less do the new essays try to cover the breadth of architecture outside the West; rather, the endeavor has been to explore the encounters and interchanges, conflicts and accommodations between the disparate global communities. Since limited space precludes providing an illustration of every building mentioned, readers are encouraged to avail themselves of the various encyclopedias and search engines available online to locate images for review.

Since the Protestant Reformation, the West has preferred to stress the written cultural record, whether historical or literary, and to give little serious attention to the meaning of visual imagery. In the United States, in most community schools (other than some private academies) there are no courses in the history of art, much less on architectural history. It is usually not until college that students first encounter art history and perhaps the history of architecture. Hence, very few young people are taught how to read or otherwise interpret the physical environment in which they will live and work. In a very few secondary schools, students are offered classes in the visual arts, music, and dance, even though only a fraction of them will put such knowledge to use explicitly when they enter the work world. In fact, because of worsening public budget constraints, even these few classes are increasingly being cut. As a result, most people are taught next to nothing about the architecture they will encounter throughout life; they learn very little about the history of their built environment or how to interpret the meaning of the environment they have inherited. What they know is literallywhat they learn in the street. This environmental illiteracy has long been accepted as the normal state of affairs.

This book seeks to bridge the gap. It is aimed at the inquisitive student or general reader interested in learning about the built environment and the layered historical meaning embodied mute within it. In short, it is intended not as a comprehensive historical survey tracing the entire evolution of built forms but rather as a basic introduction to how the environment we build works on us physically and psychologically, and what historical and symbolic messages it carries.

The basic structure of this book grew out of my outline for the architecture section of a telecourse, Humanities Through the Arts, produced in the 1970s by the Coast Community College in Fountain Valley, California, and by the City Colleges of Chicago. The idea was that architecture should be examined not only as a cultural phenomenon but also as an artistic and technological achievement. The content of the book was subsequently developed in introductory courses on architecture that I taught at The Ohio State University, Northwestern University, and the University of Oregon.