To my daughter, Melissa

Acknowledgments

I thank the following people:

Jamaica Burns Griffin and her editorial team for their patience, dedication, suggestions, and relentless search for discrepancies, omissions, and potential misunderstanding. You all contributed to a much improved final version of this book.

Jean Valnet, one of the main pioneers of aromatherapy, who, with his book The Practice of Aromatherapy, contributed greatly to the revival of this art.

Robert Tisserand, who first spread the word in the English-speaking world.

Especially Henri Viaud, a French distiller from Provence who was the first to stress the importance of long, low-pressure distillation and the use of pure and natural essential oils from specified botanical origin and chemotypes and who has not always been credited for his contribution to aromatherapy. Viaud tried to distill practically everything that could be distilled. He was the first to produce and market oils such as St. Johns wort and meadowsweet. He also revived the therapeutic use of floral waters. I learned a great deal from this wonderful honte homme, with his amazing and refreshing curiosity and eagerness for new experiments.

All humble producers who provide me with their oils.

Daniel Pnol for his pioneering work in medical aromatherapy.

All those involved in the bettering and beautifying of our planetary village.

All my students throughout the world.

All the practitioners of the aromatic art.

PREFACE TO THE 30TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

From Aroma-What to Buzzword

The Evolution of Aromatherapy

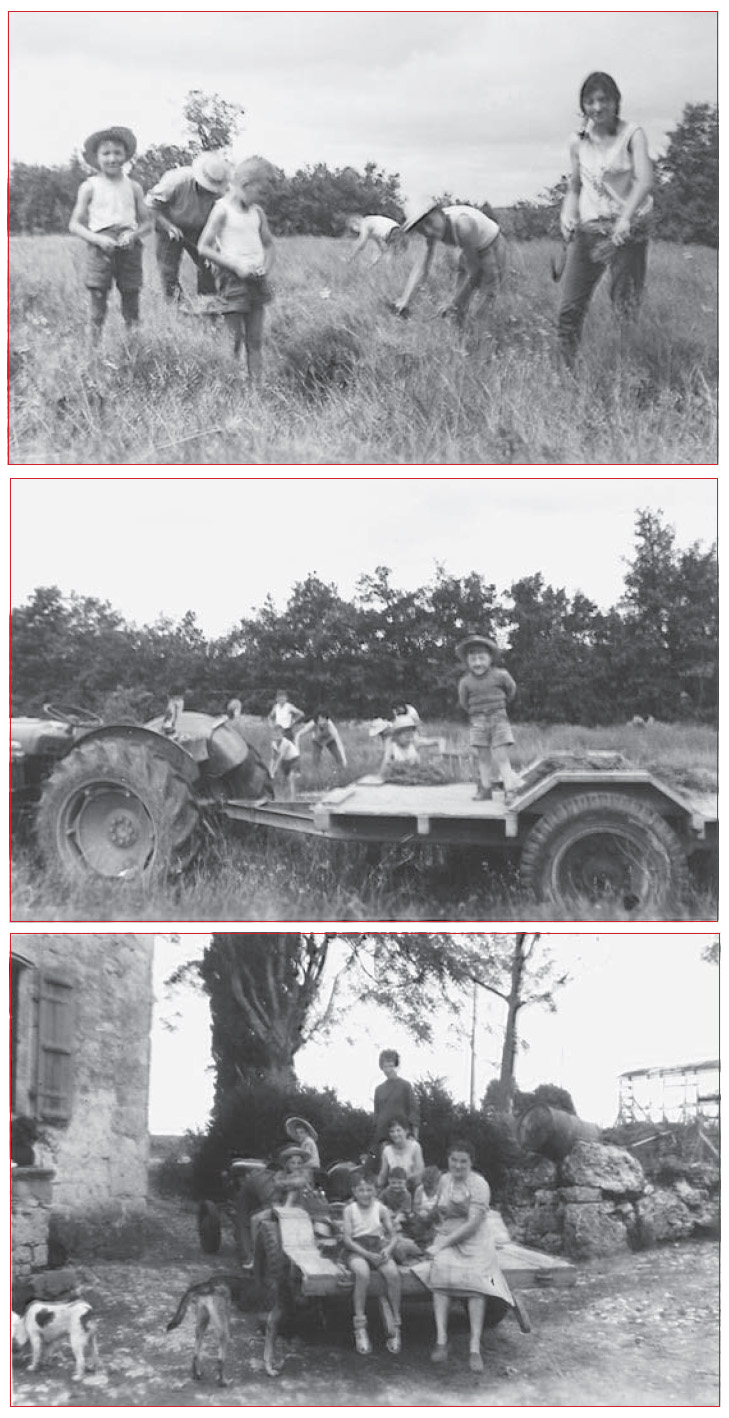

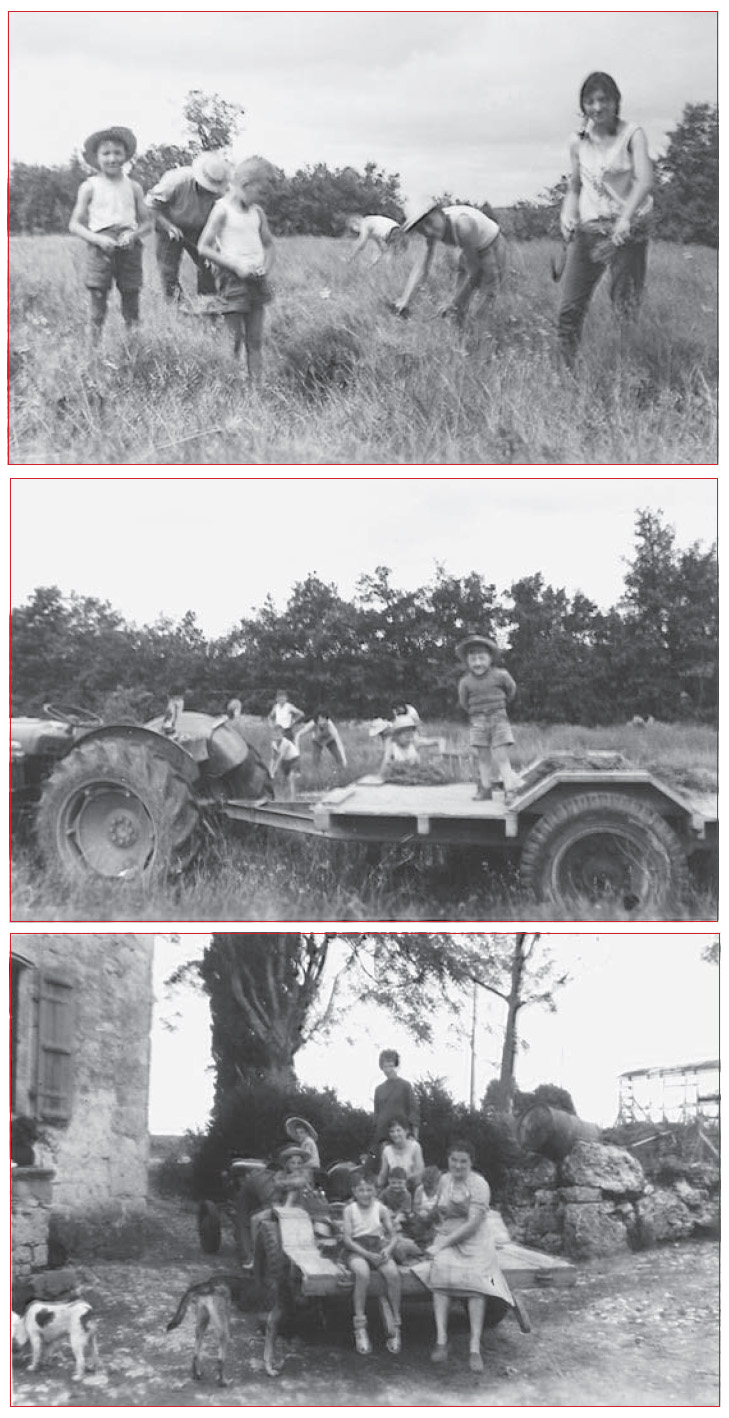

Born in 1950, I grew up on a small farm in the Quercy region of southern France at a time when the French countryside was about to undergo a radical transformation. My father was still plowing the earth with oxen when I was born, but he had bought his first tractor by the time I was three years old. We practiced subsistence farming, with a real menagerie of domestic animals, producing most of the food we needed for our own consumption, growing a little bit of everything, from the cash crops of wheat, oats, barley, and corn to all types of fruits and vegetables. We even had a small vineyard and a tiny plot of lavender.

Harvests, the highlights of the year, were a feast for the senses, starting with hay at the end of spring, followed by cherries, wheat, oats, and barley all the way to grapes, corn, apples, and walnuts in autumn, but the lavender harvest was always my favorite. The whole family would gather in the field and start cutting as soon as the morning dew had dried. We loaded the lavender onto a trailer, and we kids would all jump on top of the heap and ride to the distillery, bathing all the way in the sweet, fresh, herbal-floral fragrance.

The distillery is where the magic happened. The lavender was loaded into huge vats (at least they looked huge to us little kids), and big furnaces sent steam up through the lavender. The steam collected in the col de cygne (swan-necked lid) and passed down through the serpentin (condenser coil), and by the time it was all said and done, the big heap of lavender had been transformed into a flask of golden-green liquid with a characteristically sweet fragrance. But if anybody had asked me back then about aromatherapy, I most likely would have responded with an incredulous Aroma-what?or rather, Aroma-quoi?

Our family doctor at the time prescribed more tisanes (herbal teas) and vitamins than antibiotics and painkillers, but if you had asked him about alternative medicine, he most likely would have replied, Alternative to what?

Marcel Lavabre (as a child) and family harvesting lavender on the family farm in southern France circa 1960

Meanwhile, the French chemist and scholar Ren-Maurice Gattefoss had discovered the healing power of the essential oil of lavender when he famously burned himself in his laboratory in 1910. He coined the term aromatherapy and published his seminal book on the subject in 1937.

Jean Valnet was a French military surgeon posted to Tonkin from 1950 to 1953 during the Indochina War (which segued into the Vietnam War when the United States joined in and tried to outdo the French, with the same lack of success). The French army in Indochina often lacked even basic supplies, such as medicines and weaponry, and Valnet began experimenting with local essential oils and other aromatic and herbal preparations to treat the most severe wounds in his patients, with well above average results. His founding work, Aromathrapie: Traitement des maladies par les essences des plantes, first published in 1964 and later published in English as The Practice of Aromatherapy, is still one of the primary references on the subject.

I became familiar with aromatherapy in the mid-1970s, when I moved to the Jabron Valley, near Sisteron in the Provence region of southeastern France. The farmers there who had been collecting medicinal plants and distilling essential oils for hundreds of years had a deep knowledge of their virtues. Every mother and grandmother had her special recipes to cure all types of ailments, and they were eager to share their knowledge as the new generations were leaving this beautiful but impoverished region for the lure of the big cities.

Staffed by my horse and a mischievous donkey, I started a small enterprise harvesting wild medicinal herbs and distilling all kinds of plant material. I liked experimenting. One of my neighbors was Henri Viaud, an eccentric and fascinating gentleman-farmer, distiller, and publisher, among other occupations, with a past worthy of a cloak-and-dagger novel. Another neighbor was Pierre Lieutaghi, a living botanical encyclopedia. From Henri, Pierre, and many others, I learned a lot about herbs and their power. I should mention Madam Garcin, an outspoken healer with a witchs tendencies, who held the secret to heal burns and snakebites as well as an encyclopedic knowledge of folk medicine. Together with her son Gilles, I crisscrossed the Luberon valley and the adjoining Montagne de Lure (Lure Mountain) in search of linden, wild lavender, hyssop, thyme, savory, oregano, mugwort, wormwood, and all the bountiful aromatic and medicinal plants abounding in that region.

I moved to Boulder, Colorado, in 1981, with a suitcase full of essential oils of my own production and a few diffusers. I was intent on starting a new aromatherapy venture in the United States, but when I approached prospective customers I was met with an incredulous Aroma-what? punctuated by blank stares. It took me three months to make my first sale to an adventurous chiropractor who bought a diffuser and few essential oils for his waiting room.