Roberto Peregalli - The Embroidered Armour

Here you can read online Roberto Peregalli - The Embroidered Armour full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Pushkin Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Embroidered Armour

- Author:

- Publisher:Pushkin Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Embroidered Armour: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Embroidered Armour" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Embroidered Armour — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Embroidered Armour" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

T HE G REEKS AND THE I NVISIBLE

To the night-ramblers, magicians, Bacchants, Maenads, Mystics

Heraclitus Fragments B14

T HE LIFE OF HOMER relates that the poet, standing by Achilles tomb, wanted to see the hero in the armour made by Hephaestus, brighter than blazing fire. (Il. XVIII 609) He was blinded by its brilliance. In return he was given wisdom.

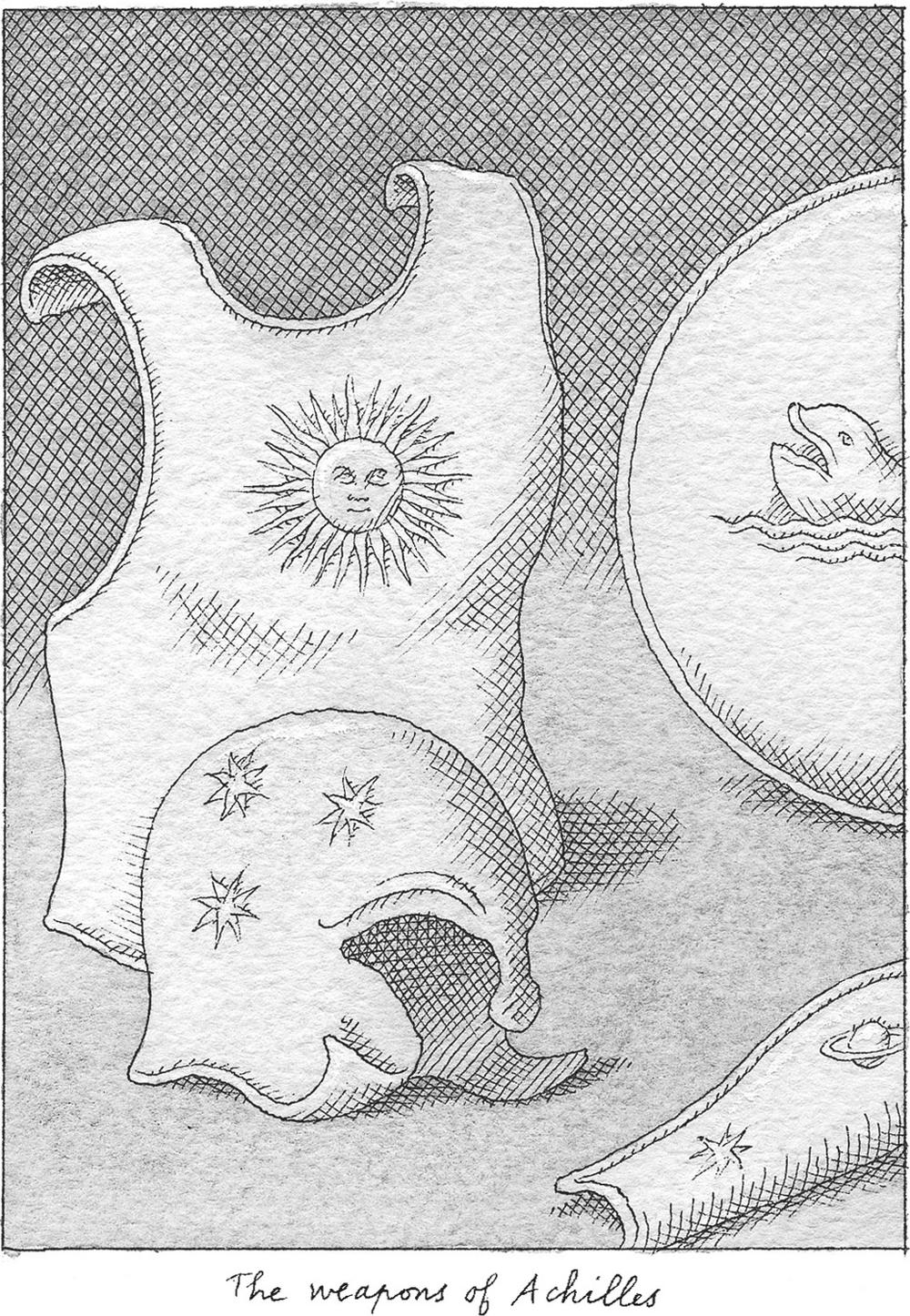

The most skilful blacksmith had forged perfect armour, too beautiful to be seen by the eyes of men. The shield, the breastplate , the helmet, the greaves. A whole universe was sculpted within them. He decorated it with earth, sky and sea, the tireless sun, the full moon, and all the constellations with which the skies are crowned. (Il. XVIII 483485) And then the doings of men, places, wars.

Homer wanted to see. Hence he wished to know what was revealed. The disclosure, to the eyes, of that which is hidden concerns truth.

Seeing for the Greeks is knowing. For that reason they are known as the people of the eye. That which is hidden is taken from the darkness of the invisible and brought into the light. The distance that separates that space and keeps it together generates the very possibility of knowledge. And, as such, it is precisely because of its tragic essence, in that it presupposes that two incommensurable worlds, that of the visible and that of the invisible, enter into communication with one another.

Homer wishes to see Achilles gleaming armour because the truth is inscribed within it. The splendour of that which is revealed to the light dims the vision. The dappled cloak of the

The concept of the tragic is produced and arranged within this space. The relationship of mortals to the world is based on what may be seen. But the truth of this is hidden, or only fitfully apparent. So for a people that connects knowledge with sight, fracture, mask. The invisible is an obstacle to knowledge. So it must be revealed. Truth is the revelation of that which is hidden.

Hence the way towards truth is the attempt to overcome that which is by its essence invisible. The Greeks want to see everything , to embrace the whole of the horizon with their eyes. In this seeing everything, the link between sight and knowledge becomes clear. That which is seen, insofar as it comes to light, is true. But the movement of appearing, condensed in the gaze, is possible only as emergence from hiding.

The words true (a-lethes) and invisible (a-delon) are at the same time mirror images and opposites. But their connection is evident: the negation of hiddenness certifies its existence. If that which is visible is true, it is true also that truth has its origin in that which cannot be seen. In the Greek world it is thus the ambiguous essence of truth which from the outset connects the visible and the invisible.

The invisible is the shadow of the visible, its hidden bottom. The interesting thing about this word, a-delon, lies precisely in the difficulty of its appearance. The Greeks were sparing in their mentions of it until Plato. In Homer it occurs on one occasion Blindness, then, is an absence of completeness.

However, this negativity, parallel with that of truth (a-letheia) with its privative a, seems to constitute its reverse, that of darkness. The invisible is part of all that cannot be mastered with the gaze, and thus, for a pre-Platonic Greek, with the mind. Being unmasterable, it constitutes a point of darkness. And it is upon this darkness, at the boundary between darkness and light, that Greek wisdom is structured.

The visible hides vast depths. But for the Greeks what matters is to remain on the surface. From this derives the antinomy that forms the tragic element within their thought. Grasping the invisible means losing the lightness, the plasticity linked with sight, which represents for them an irrefutable presupposition.

Hence, capturing the invisible means leaving the structure of one world in order to enter another. The Greeks perceive this as a transgression, and, as such, a sin. Crossing the confines reserved for the possibilities of men means, for them, wanting to confront death, seeking in vain to overcome it.

At the same time Achilles gleaming armour is what is most noteworthy, that which it is worth letting the gaze linger over. In a single moment, in its sudden gleam, the very possibility of knowledge unfolds. And furthermore, only insofar as it becomes visible does it produce wisdom.

This profound antinomy runs through Greek wisdom from its earliest beginnings. The path starts in Homer and concludes with Plato. It is a path towards darkness and death. The position with regard to the gaze is inverted. The importance of that which is not seen becomes the ontological constitution of an unattainable truth.

The subtle distinction between truth (a-letheia) and invisible (a-delon) vanishes. The invisible becomes that which is true. Homers world which knows no background, the trust in the gaze, the truth of the visible, which can be a source of wisdom only in that it shows itself, are no longer enough. The gaze, resting on all that is visible, apparent, is fallacious. To capture the truth we must close our eyes to visible things. That is the gesture performed before Hades, the lord of the dead. The tragic origin of knowledge is apparent in all its force. Once the veil of the gaze has been removed, the flashing splendour of Olympus is inverted to become a vision of Hades.

The connection between truth and the invisible creates the arduous journey from that which is seen to that which is hidden. It is there that the mysteries, the word, Memory show themselves. With Plato this transformation is taken to its conclusion. In his dialogues, playing with words as an accomplished Sophist, he structures a new vision of the world.

The race of men most capable of seducing us into life creates the soul, that hidden and nocturnal fragment that lies within man. The gleaming fascination of the images sculpted on Achilles shield is translated in interiorem hominem. The sight of the body is dimmed to make way for that of the soul. While blindness, supported by double vision, will no longer communicate with the gods.

The path that connects that which is seen to the invisible bottom of things, and its tortuous journey through the subtle space in which the Greeks placed knowledge and death, are the fabric of this essay.

Introduction J Burckhardt, Storia della civilt greca, (Florence, Sansoni, 1955, original ed. 18981902), p 706.

Cf M Heidegger, Platos Doctrine of Truth, trans Thomas Sheehan, Stanford University Press.

G Kittel, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, trans and ed Geoffrey W Bromiley, Michigan 1964, s v: orao.

Burckhardt, Storia della civilt greca, p 507.

E Auerbach, Mimesis. The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, Trans Willard R Trask, Princeton, 1953, pp 39.

This word, in its tragic sense, will be one of this books fundamental motifs.

Aristotle, Metaphysics, V, 15, 1021a.

The word invisible is represented in the Greek language (until Plato) by three different words: adelon, aphanes, aoraton. A fourth word, aides, added to Platos lexicon, will be considered in chapter 8. This multiplicity, rather than stressing translatability of a different kind, constitutes the most dazzling proof of the varied structure of its meaning. The verbs

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Embroidered Armour»

Look at similar books to The Embroidered Armour. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Embroidered Armour and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.